Despite the years of civil war and insurgency that followed, the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq was a well-planned and well-timed operation, so successful in its initial phases that American and Coalition forces had captured Baghdad within just three weeks. Major combat operations famously ended on May 1, 2003, in less than two months. But despite the speed and skill of the Americans, it was not without considerable effort – or losses.

One of those losses was SFC Paul Ray Smith, a veteran of both the first Gulf War and the Kosovo War. In April 2003, Smith was leading the men of B Company, 11th Engineer Battalion, 3rd Infantry Division, to capture the international airport in Baghdad. While blocking the highway between the city and the airport, he found himself in a crossfire between counterattacking Iraqi forces. Unable to withdraw, he fought against overwhelming odds, giving his life to prevent an aid station from being overrun.

One of those losses was SFC Paul Ray Smith, a veteran of both the first Gulf War and the Kosovo War. In April 2003, Smith was leading the men of B Company, 11th Engineer Battalion, 3rd Infantry Division, to capture the international airport in Baghdad. While blocking the highway between the city and the airport, he found himself in a crossfire between counterattacking Iraqi forces. Unable to withdraw, he fought against overwhelming odds, giving his life to prevent an aid station from being overrun.

Paul Ray Smith was born on September 24, 1969, in El Paso, Texas, but his family moved to Tampa, Florida, when he was still young. He was outgoing, athletic, and enjoyed being part of a team, which is probably one of the reasons he joined the Army after graduating from high school. Before long, he was stationed in Germany, got married, and had children. He served his country as a combat engineer in Kuwait during the Gulf War and again in Bosnia as part of the NATO peacekeeping forces there. During the 2003 Invasion of Iraq, he was a senior non-commissioned officer, still leading combat engineers.

His unit crossed into Iraq on March 19, 2003, moving more than 186 miles into enemy territory in just 48 hours to support Task Force 2-7 Infantry. By April 3, Bravo company was in Baghdad as part of the 3rd Infantry Division's push to capture Baghdad International Airport. Task Force 2-7 was assigned to block the roads to the airport against a brigade-sized counterattack. After three days of continuous fighting, morale was high, but so was fatigue. Smith and his men were positioned along the main route for the enemy's incoming attack, a four-lane highway with a median separating the two directions. The area held 100 soldiers, including mortars, scouts, and an aid station.

With his platoon leader out on patrol, Smith was assigned to create an enemy POW holding area from one of the walled compounds that dotted the highway. The compound's watchtower would provide oversight for the guards manning the POW area.

With his platoon leader out on patrol, Smith was assigned to create an enemy POW holding area from one of the walled compounds that dotted the highway. The compound's watchtower would provide oversight for the guards manning the POW area.

Using an M9 armored combat earthmover (a protected bulldozer), he knocked a hole in the walls of one of the compounds, gaining access to a courtyard with a metal gate at the north end of the wall. As engineers cleared away debris, they spotted enemy troops with small arms, mortars, and rocket-propelled grenades forming to attack, lead elements of a coming assault by a larger force. Smith noticed as many as 50 or more. Smith had only 16 soldiers to defend the roadblock and aid station. He needed more firepower.

He immediately called for a Bradley Armored Fighting Vehicle to support the defense of the roadblock, and he instructed his men to grab anti-tank weapons and form a skirmish line. By the time he organized the American defenders, the Iraqi force had grown to 100 strong. Enemy forces also occupied the surrounding guard towers. Three M113A3 APCs joined the American defense, with .50-caliber machine guns focused on those towers. As the shooting started, Smith moved forward with two soldiers to join the guards at the north gate.

As he threw a grenade at the enemy, he directed fire at the incoming fire at incoming Iraqis, who were now fully engaged with bullets, rockets, and 60mm mortars. As Iraqis began to head toward the towers along the north wall, Smith directed an APC to provide more fire support.

After the Bradley took direct hits from an RPG and was running low on ammunition, the lead APC took a direct hit from an Iraqi mortar, wounding the three crewmen inside. As the Bradley withdrew to reload, he ordered one of his soldiers to back it into the courtyard and manned the APC's .50-cal. amid a withering crossfire from the front and from the towers. He told the other soldier with him to "feed me ammunition whenever you hear the gun get quiet."

After the Bradley took direct hits from an RPG and was running low on ammunition, the lead APC took a direct hit from an Iraqi mortar, wounding the three crewmen inside. As the Bradley withdrew to reload, he ordered one of his soldiers to back it into the courtyard and manned the APC's .50-cal. amid a withering crossfire from the front and from the towers. He told the other soldier with him to "feed me ammunition whenever you hear the gun get quiet."

Unprotected in the mounted machine gun, Smith went through three boxes of ammo before he was mortally wounded. He was found in the machine gun turret with 13 holes in his protective vest, shattering the ceramic plates. By leading the defense and taking up the largest gun between the enemy and the aid station, Smith ensured the failure of the Iraqi assault while saving the lives of 100 wounded soldiers and inflicting as many as 50 enemy casualties.

Before deploying to Iraq, Smith wrote to his parents: "There are two ways to come home, stepping off the plane and being carried off the plane. It doesn't matter how I come home because I am prepared to give all that I am to ensure that all my boys make it home."

On April 4, 2005, two years to the day after he was killed in action, President George W. Bush presented the Medal of Honor to the family of Sgt. 1st Class Paul Ray Smith at a White House ceremony. Smith was the first recipient to also receive the newly-authorized Medal of Honor flag. Although he has a memorial plaque at Arlington National Cemetery, his cremated remains were spread across the Gulf of Mexico, where he loved to fish.

The Revolutionary War Battle at Guilford Courthouse in North Carolina is not just an important moment for American independence; it's a good lesson for everyone to remember. There are times when, no matter how hard you fight or how badly you want to win, you might still lose. But that loss could lead to an even more important battle—and a greater, more important victory.

After its 1777 loss at the Battle of Saratoga, the British Army's strategy to put down the colonial rebellion refocused on the south, where support for the mother country was strongest. Although the campaign itself was more successful than in the north, the British under Lord Cornwallis still suffered some heavy defeats. American militia held their ground at Cowpens, and the collapsing British lost a quarter of their overall strength in the southern colonies. Focused solely on destroying American Nathaniel Greene's Army, Cornwallis burned his baggage train, taking only his wounded warfighting necessities: ammunition, medical supplies, and salt.

After its 1777 loss at the Battle of Saratoga, the British Army's strategy to put down the colonial rebellion refocused on the south, where support for the mother country was strongest. Although the campaign itself was more successful than in the north, the British under Lord Cornwallis still suffered some heavy defeats. American militia held their ground at Cowpens, and the collapsing British lost a quarter of their overall strength in the southern colonies. Focused solely on destroying American Nathaniel Greene's Army, Cornwallis burned his baggage train, taking only his wounded warfighting necessities: ammunition, medical supplies, and salt.

Starving, dying, and plundering the locals for food, the British caught up with Greene at Guilford Courthouse on March 15, 1871, where they were outnumbered by more than two-to-one. He would force Greene and the Americans into a confrontation there, one remembered as "the most hotly contested action of the Revolutionary War in the Southern Campaign." But Cornwallis reportedly didn't care: he didn't even know how many Americans were there. For the British, winning the battle meant the difference between life and death.

The battle did not start well for the British. They walked along a road in a column, straight into Greene's three lines of defense. The North Carolina militia in the first line held their ground, firing a devastating volley into the redcoats. As Cornwallis' men moved out of the woods along the road, they found themselves in an enfilade, taking fire from two sides, but they held their own fire until they were certain of inflicting maximum pain on the rebels. Once they fired off their own volley, they surged ahead and dispersed the first line.

Greene's second line was made up of Virginians, who put up a stiff resistance to the incoming British. But the desperate British infantry attacking on all sides soon overwhelmed them, and they too were forced to retreat. Greene's defense in depth was falling apart, but so was the British organization. The redcoats were fragmented as they hit the third line of defense. Their first assault was pushed back by a joint force of Virginians and Marylanders. The Marylanders folded when the British advanced the second time but were pushed back in a colonial counterattack.

Greene's second line was made up of Virginians, who put up a stiff resistance to the incoming British. But the desperate British infantry attacking on all sides soon overwhelmed them, and they too were forced to retreat. Greene's defense in depth was falling apart, but so was the British organization. The redcoats were fragmented as they hit the third line of defense. Their first assault was pushed back by a joint force of Virginians and Marylanders. The Marylanders folded when the British advanced the second time but were pushed back in a colonial counterattack.

The attackers began to grow stronger as the American second line collapsed, and more and more British regulars began to assault the third line. Cornwallis then fired grapeshot into the melee, killing colonials and British troops alike. In response, Greene ordered his men to withdraw. In 90 minutes, the British were victorious, but Cornwallis had ruined his army. A full 27% of his force became casualties, and he was unable to follow up on his victory. Moreover, they still had no food or shelter.

Cornwallis retreated to Wilmington to refit his army, effectively abandoning the colonies he'd just won in the south. By May 1871, he would take his forces into Yorktown, where a combined Franco-American force under Gen. George Washington would force his surrender before the end of October. For Nathaniel Greene, losing a battle despite superior numbers and defenses must have stung, but the cost he forced Cornwallis to pay ensured the future independence he was fighting for in the first place.

When I first found TWS, which was completely by accident (surfing the web), it was as a result of my attempt to locate many missing Brothers in Arms that I had served with. Now, being somewhat of a computer geek, I was not very inclined to signing or "getting on board" with yet another website that touted its military association. However, after deciding (through frustration, if nothing else) to sign up, I began to realize that not only was the site an attractive site, but it was well thought-out and well-maintained as well. Thus began my "affair" with TWS. At first, in order to avoid having to pay anything, I started an effort to bring on board as many new participants as possible. But mind, this was partly due because I had already located more of my missing com-padres than any other previous source before, combined; thus, my motivation was supportable. Although I will say I do not "live" on the site as much as I used to, I have been a proactive member of its content and affairs, having attended TWS events and site change involvement. I have also become a lifetime member (what'd I tell you, it must have presented a viable enough purpose to have me pocket the Lifetime Membership). I tell people that I recommend TWS for a couple of very solid reasons: Firstly, because it is the single best website for Marines (and other services) to locate missing fellow service members; secondly, because it is the best designed and maintained (military-related) website I have seen; thirdly because it is "fluid;" constantly changing and finding ways to improve its services, esthetics, and purpose.

MSgt George Sidler, US Marine Corps (Ret)

Served 1973-2000

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive was the final push of World War I on the Western Front, lasting from Sept. 28, 1918, until the end of the war, Nov. 11, 1918. The allied forces of Britain, France, and the United States advanced all along the front, making the largest offensive in U.S. military history, involving more than 1.2 million troops. It was also the deadliest, inflicting 350,000 casualties in less than seven weeks. The allies made relatively major gains, considering the course of the war until that point, but it was not without errors – and one of those errors meant the loss of a battalion-sized force.

The men of that battalion came from the 77th Division, made up mostly of men from New York City. During the allied push, they fought their way into the dense Argonne Forest, where a counterattack soon left them surrounded and cut off from friendly lines. Thinking the unit had been lost, allied artillery shelled their position while German troops repeatedly attacked them from all sides. When word finally got to the allied command, an entire division was sent to relieve them – but would they make it in time?

The men of that battalion came from the 77th Division, made up mostly of men from New York City. During the allied push, they fought their way into the dense Argonne Forest, where a counterattack soon left them surrounded and cut off from friendly lines. Thinking the unit had been lost, allied artillery shelled their position while German troops repeatedly attacked them from all sides. When word finally got to the allied command, an entire division was sent to relieve them – but would they make it in time?

When the Meuse-Argonne Offensive launched, officers in the Argonne Forest region were given specific orders that no one was allowed to fall back for any reason. The 77th Division launched its thrust into the forest with the French on their left flank and two American units on their right. The Germans had held the area since the beginning of the war and were well entrenched. Deep trenches, barbed wire, interlocking machine guns, and pre-sighted artillery awaited any attacker who dared to make the one-mile march across no-man's land in the Argonne.

By the morning of Oct. 2, the 77th had progressed through all of its initial four objectives. Their next objective was to capture Hill 198, which would allow them to flank the German defenders in the forest. Soldiers reconnoitering the hill found a way to get up to it along its right side. As they crested the top of the hill, they had no idea the Germans had already pushed back both of their flanks. Some 545 men from various units within the 77th with Maj. Whittlesey, in command, was now surrounded and cut off. Whittlesey only realized it when he could no longer hear anyone around them.

The 77th began to dig in, with the hill next to them and the ravine below them occupied by the enemy. That same afternoon, the Germans attacked them from all sides of the hill. Mortars, grenades, and snipers tried to dislodge the Americans, but Whittlesey stayed put. He sent out runners to make contact with French or American units, but no one ever returned. The only consolation was that the Germans took as many casualties as they did. As if that wasn't bad enough, they were taking artillery fire from their own side.

The 77th began to dig in, with the hill next to them and the ravine below them occupied by the enemy. That same afternoon, the Germans attacked them from all sides of the hill. Mortars, grenades, and snipers tried to dislodge the Americans, but Whittlesey stayed put. He sent out runners to make contact with French or American units, but no one ever returned. The only consolation was that the Germans took as many casualties as they did. As if that wasn't bad enough, they were taking artillery fire from their own side.

Whittlesey had no idea if anyone back at headquarters even knew if they were missing. Low on food and ammunition, he sent his last carrier pigeon in a desperate attempt to get help. Luckily, that pigeon was Cher Ami, now famous for carrying the major's message. The bird was shot down twice but managed to fly back to headquarters 25 miles away with the message: "We are along the road parallel to 276.4. Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heaven's sake, stop it." Cher Ami arrived having been shot through the breast, blinded in one eye, and with a leg hanging only by a tendon.

But when the allied shelling finally stopped, the Germans attacked yet again, this time reaching close enough to fight in hand-to-hand combat. Again, the 77th fought them off. For the next three days, the two sides fought over the hill. Back at the front, the main body of the 77th launched a series of attacks to get to the Lost Battalion, but all failed.

When news of the situation reached the American Expeditionary Force headquarters, Gen. John J. Pershing sent the 28th Infantry Division, reinforced by the 82nd Infantry Division and the 1st Infantry Division, all under the command of Gen. Hunter Liggett, to relieve them.

When news of the situation reached the American Expeditionary Force headquarters, Gen. John J. Pershing sent the 28th Infantry Division, reinforced by the 82nd Infantry Division and the 1st Infantry Division, all under the command of Gen. Hunter Liggett, to relieve them.

The Germans saw the forces being arrayed against them, so they reinforced their own lines and sent flamethrower troops to Hill 198 to dislodge Whittlesey. Not only did the powerful American army begin to move the line, the Lost Battalion also held out. Whittlesey sent out Pvt. Abraham Krotoshinsky was to lead advancing friendly forces in the beleaguered unit. On Oct. 8, 1918, they finally arrived. Only 194 members of the Lost Battalion avoided becoming casualties on the hill.

Whittlesey was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and received the Medal of Honor, along with six others. Private Krotoshinsky and 30 others would receive the Distinguished Service Cross.

"…So many more, subs by the score, went to their watery grave,

In silence deep, they lie asleep, the young lads and the brave,

But this I know, somewhere below lie those who paid the price,

Our debt is paid because they made the final sacrifice."

By: Robert L. Harrison

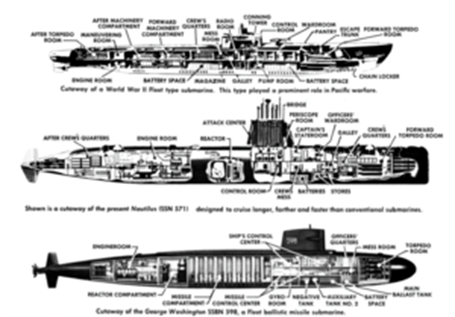

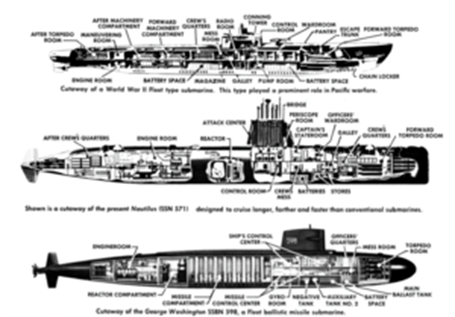

A submarine carrying the name USS Halibut has seen service under three designations. USS Halibut I (a Gato-class boat (SS-232) from 1942-45) was the first vessel of the United States Navy to be named for the halibut, a large, up to 500-pound species of flatfish typically found at the bottom of relatively shallow waters in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Of the original WWII Halibut, Commander Graham C. Scarbro (USN) poignantly wrote, "The Gato-class submarine USS Halibut (SS-232) slid through the waters of the Luzon Strait, prowling for Japanese surface vessels." As the sun rose over her stern on 14 November 1944, her skipper, Lieutenant Commander Ignatius J. "Pete" Galantin, ordered the boat to dive. Increased aerial traffic observed during the night was a promising sign that the Halibut was in the right place. Galantin had a hunch that Japanese shipping, bound to reinforce or resupply beleaguered enemy troops in the Philippines, would soon pass through the Bashi Channel at the north end of the strait.

A submarine carrying the name USS Halibut has seen service under three designations. USS Halibut I (a Gato-class boat (SS-232) from 1942-45) was the first vessel of the United States Navy to be named for the halibut, a large, up to 500-pound species of flatfish typically found at the bottom of relatively shallow waters in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Of the original WWII Halibut, Commander Graham C. Scarbro (USN) poignantly wrote, "The Gato-class submarine USS Halibut (SS-232) slid through the waters of the Luzon Strait, prowling for Japanese surface vessels." As the sun rose over her stern on 14 November 1944, her skipper, Lieutenant Commander Ignatius J. "Pete" Galantin, ordered the boat to dive. Increased aerial traffic observed during the night was a promising sign that the Halibut was in the right place. Galantin had a hunch that Japanese shipping, bound to reinforce or resupply beleaguered enemy troops in the Philippines, would soon pass through the Bashi Channel at the north end of the strait.

Operating alongside the USS Haddock (SS-231) and Tuna (SS-203), she had sunk the Japanese destroyer Akizuki during the Battle of Leyte Gulf three weeks before. Now the crew, a mix of plank owners, veterans, and new recruits, was ready for more. They did not know this would be the Halibut’s final cruise… with the war in the Pacific winding down, the Navy determined damage to Halibut in the Luzon strait [‘The crew toiled with repairs, and when night came she resurfaced… The radar was repaired, although Halibut was without depth gauges, main compasses, gyros, radio, and a number of other systems. Most of the damage was actually to the hull and its fittings.’] It was too extensive to justify repairing the boat, and she was scheduled for decommissioning. Plans to convert her to a school ship did not materialize, and she was sold for scrap for $23,123. Over her ten war patrols, the Halibut won seven battle stars and sank 12 enemy ships totaling 45,257 tons; she damaged 13 more enemy vessels." Her skipper earned the Navy Cross and Silver Star.

From 1960-76, there was the USS Halibut II (SSGN-587), built at Mare Island and commissioned on 4 Jan. It was converted to an Attack Submarine at Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard from 6 Feb 1965 to 6 Sep 1965 and redesignated (SSN-587) on 8 Aug 1965. It displaced 3.655 tons (5,000 tons submerged) at a length of 350 feet with a beam of 29 feet. The vessel’s complement was 9-10 officers and 88 enlisted. Its armament consisted of one Regulus I missile launcher, and Halibut could carry five in the hangar. In addition, it had six 21" torpedo tubes (4 forward & 2 aft). It was powered by the S3G nuclear reactor with twin 5-bladed propellers and had been awarded two Presidential Unit Citations, two (or possibly three) Navy Unit Commendations, the Navy E ribbon, and the National Defense Service Medal.

From 1960-76, there was the USS Halibut II (SSGN-587), built at Mare Island and commissioned on 4 Jan. It was converted to an Attack Submarine at Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard from 6 Feb 1965 to 6 Sep 1965 and redesignated (SSN-587) on 8 Aug 1965. It displaced 3.655 tons (5,000 tons submerged) at a length of 350 feet with a beam of 29 feet. The vessel’s complement was 9-10 officers and 88 enlisted. Its armament consisted of one Regulus I missile launcher, and Halibut could carry five in the hangar. In addition, it had six 21" torpedo tubes (4 forward & 2 aft). It was powered by the S3G nuclear reactor with twin 5-bladed propellers and had been awarded two Presidential Unit Citations, two (or possibly three) Navy Unit Commendations, the Navy E ribbon, and the National Defense Service Medal.

The nuclear USS Halibut was the first submarine in the world, designed and built from the keel up, to launch guided missiles. She was also the first submarine to carry the Ships Inertial Navigation System (SINS). In September 1959, with the 1st patrol of Grayback, an era of submarine history began that would go unrecognized for almost 40 years. Five Regulus submarines: USS Grayback (SSG 574), USS Tunny (SSG 282), USS Barbero (SSG 317), USS Growler (SSG 577) and USS Halibut (SSGN 587) deployed on 41 deterrent patrols under the earth's oceans over the course of 5 years. These deterrent patrols represented the first ever in the history of the submarine Navy and preceded those made by the Polaris missile firing submarines. Navy TWS lists 57 registered members who served aboard this vessel.

The SSM-N-8A Regulus weapon borne by the last USS Halibut was a US Navy-developed ship-and-submarine-launched, nuclear-capable, turbojet-powered second-generation cruise missile, deployed from 1955 to 1964. Its development was an outgrowth of tests cond ucted with the German V-1 missile at NAS Point Mugu in California. Its barrel-shaped fuselage resembled that of numerous fighter aircraft designs of the post-WWII era, but without a cockpit. When the missiles were deployed, they were launched from a rail launcher and equipped with a pair of Aerojet JATO bottles on the aft end of the fuselage. Halibut, with its extremely large internal hangar, could carry five missiles and was intended to be the prototype of a whole new class of cruise missile-firing SSG-N submarines. Despite being the U.S. Navy's first underwater nuclear capability, the Regulus missile system had significant operational drawbacks. In order to launch, the submarine had to surface and assemble the missile in whatever sea conditions it was in. "Because it required active radar guidance, which only had a range of 225 nmi (259 mi; 417 km), the ship had to stay stationary on the surface to guide it to the target while effectively broadcasting its location. This guidance method was susceptible to jamming, and since the missile was subsonic, the launch platform remained exposed and vulnerable to attack during its flight duration; destroying the ship would effectively disable the missile in flight." A second-generation supersonic Vought SSM-N-9 Regulus II cruise missile with a range of 1,200 nautical miles (2,200 km) and a speed of Mach 2 was developed and successfully tested, including a test launch from Halibut’s sister, the Grayback, but the program was canceled in favor of the UGM-27 Polaris nuclear ballistic missile. Both Regulus I and Regulus II were used as target drones after 1964.

ucted with the German V-1 missile at NAS Point Mugu in California. Its barrel-shaped fuselage resembled that of numerous fighter aircraft designs of the post-WWII era, but without a cockpit. When the missiles were deployed, they were launched from a rail launcher and equipped with a pair of Aerojet JATO bottles on the aft end of the fuselage. Halibut, with its extremely large internal hangar, could carry five missiles and was intended to be the prototype of a whole new class of cruise missile-firing SSG-N submarines. Despite being the U.S. Navy's first underwater nuclear capability, the Regulus missile system had significant operational drawbacks. In order to launch, the submarine had to surface and assemble the missile in whatever sea conditions it was in. "Because it required active radar guidance, which only had a range of 225 nmi (259 mi; 417 km), the ship had to stay stationary on the surface to guide it to the target while effectively broadcasting its location. This guidance method was susceptible to jamming, and since the missile was subsonic, the launch platform remained exposed and vulnerable to attack during its flight duration; destroying the ship would effectively disable the missile in flight." A second-generation supersonic Vought SSM-N-9 Regulus II cruise missile with a range of 1,200 nautical miles (2,200 km) and a speed of Mach 2 was developed and successfully tested, including a test launch from Halibut’s sister, the Grayback, but the program was canceled in favor of the UGM-27 Polaris nuclear ballistic missile. Both Regulus I and Regulus II were used as target drones after 1964.

Halibut II was originally designed under project SCB 137 as a diesel-electric submarine but was completed with nuclear power under SCB 137A. (SSGN-587) was the first submarine initially designed to launch guided missiles. Intended to carry the Regulus I and Regulus II nuclear cruise missiles, her main deck was high above the waterline to provide a dry flight deck. Her missile system was completely automated, with hydraulic machinery controlled from a central control station. On 25 Mar 1960, while underway to Australia, she became the first nuclear-powered submarine to successfully launch a guided missile. Between February 1961 and July 1964, Halibut undertook seven deterrent patrols before being replaced in the Pacific by UGM-27 Polaris-equipped submarines of the Lafayette class. From September through December 1964, she joined eight other submarines in testing and evaluating the attack capabilities of the Permit-class submarine.

According to the documentary Regulus: The First Nuclear Missile Submarines, the primary target for Halibut in the event of a nuclear exchange would be to eliminate the Soviet naval base at Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. The patrols made by Halibut and its sister Regulus-firing submarines represented the first ever deterrent patrols in the history of the submarine navy, preceding those made by the Polaris missile-firing submarines. Halibut was used in underwater espionage missions by the US against the Soviet Union. Her most notable accomplishments included:

According to the documentary Regulus: The First Nuclear Missile Submarines, the primary target for Halibut in the event of a nuclear exchange would be to eliminate the Soviet naval base at Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. The patrols made by Halibut and its sister Regulus-firing submarines represented the first ever deterrent patrols in the history of the submarine navy, preceding those made by the Polaris missile-firing submarines. Halibut was used in underwater espionage missions by the US against the Soviet Union. Her most notable accomplishments included:

• The underwater tapping of a Soviet communication line running from the Kamchatka peninsula west to the Soviet mainland in the Sea of Okhotsk (Operation Ivy Bells)

• Surveying sunken Soviet submarine K-129 in August 1968, before the CIA’s Project Azorian.

The latter mission is profiled in the 1996 book, Spy Sub – A Top Secret Mission to the Bottom of the Pacific, by Dr. Roger C. Dunham, although Dunham was required to change the name of Halibut to that of the non-existent USS Viperfish with a false hull number of SSN-655 to pass Department of Defense security restrictions for publication. The vessel was decommissioned on 30 Jun 1976 and laid up awaiting disposal under the Nuclear Powered Ship and Submarine Recycling Program at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Bremerton, WA. It was struck from the Naval Register on 30 Apr 1986 and then disposed of through NPSSRP on 9 Sep 1994. The US Navy has the largest nuclear-powered fleet in the world. The first nuclear-powered submarine in the US Navy was the USS Nautilus, which launched in 1954. Our submarine force is known for its covert operations, which require the ability to operate without detection. One of the slogans associated with the Submarine Force is "Silent Service".

My father was in the Navy in the Pacific and saw action from Guadalcanal to Okinawa. My oldest brother retired from the Navy Reserve as a Master Chief Corpsman after 30+ years. My youngest brother served as a Staff Sergeant in the Marine Corps. My oldest son served as an Electricians Mate 2nd Class aboard a fast attack nuclear submarine.

For them and for myself, I can say that I am proud to have served my country and very much appreciate the platform that Together We Served offers as a means to record our service and to reach out to others who have served as well.

Served 1970-1974

If you think porch pirates stealing your Amazon packages is a pervasive threat to the American way of life, it's nothing compared to the postal heists of the 1920s. The Roaring Twenties was when crime in America became organized, widespread, and increasingly violent. The prohibition of alcohol led to bootlegging and gang violence, along with a surge of bank robberies, kidnappings, and auto thefts. Even the U.S. Mail was not exempt from the rising crime wave.

Between 1920 and 1921 alone, thieves stole an estimated $86 million (adjusted for inflation) over 36 robberies of the U.S. Postal Service. With 250,000 miles of postal railway, adequately guarding the mail was nearly impossible for just 500 postal inspectors. What could the government do to protect the mail?

Between 1920 and 1921 alone, thieves stole an estimated $86 million (adjusted for inflation) over 36 robberies of the U.S. Postal Service. With 250,000 miles of postal railway, adequately guarding the mail was nearly impossible for just 500 postal inspectors. What could the government do to protect the mail?

They called in the Marines.

President Warren G. Harding's Postmaster General was the highly respected Will Hays. When Hays told the president he needed help guarding the mailways, Harding used the United States Marine Corps.

After World War I ended in 1918, the Corps faced severe manpower drawdowns, but its operations never slowed down. Along with American interventions in Central and South America, the Marines were preparing to become the Fleet Marine Force that would master amphibious landings to win a war in the Pacific. But that would have to wait for 50 officers and 2,000 enlisted men.

In 1921, those Marines were posted at some of the United States' most pernicious locations, places where mail cars were just waiting to be robbed. Their orders from Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby were clear: if attacked, kill the attackers.

"To the Men of the Mail Guard, you must, when on guard duty, keep your weapons in hand and, if attacked, shoot and shoot to kill," Denby said. "If two Marines are covered by a robber, neither must put up his hands, but both must immediately go for their guns. One may die, but the other will get the robber, and the mail will get through."

"To the Men of the Mail Guard, you must, when on guard duty, keep your weapons in hand and, if attacked, shoot and shoot to kill," Denby said. "If two Marines are covered by a robber, neither must put up his hands, but both must immediately go for their guns. One may die, but the other will get the robber, and the mail will get through."

The general orders were just as simple:

1. To prevent the theft or robbery of any United States mail entrusted to my protection.

2. To inform myself as to the persons who are authorized to handle the mail entrusted to my protection and to allow no unauthorized persons to handle such mail or to have access to such mail.

3. To inform myself as to the persons who are authorized to enter the compartment (railway coast, auto truck, wagon, mail room, etc.) where mail entrusted to my protection are placed, and to allow no unauthorized person to enter such compartment.

4. In connection with Special Order No. 3, to prevent unauthorized persons loitering in the vicinity of such compartment or taking any position from which they might enter such compartment by surprise or sudden movement.

5. To keep my rifle, shotgun, or pistol always in my hand (or hands) while on watch.

6. When necessary in order to carry out the foregoing orders, to make the most effective use of my weapons, shooting or otherwise killing or disabling any person engaged in the theft or robbery, or the attempted theft or robbery of the mails entrusted to my protection.

Potential robbers and gangsters apparently sought out easier targets once the Marine Corps deployed to guard the U.S. mail. By the end of 1921, the robberies of post offices, USPS train cars, and even individual mail carriers had ceased. The last Marines on mail guard duty ended their tours in March 1922, and the mail seemed safe. But that wasn't the end of violent crime sprees in America. Before the year was out, mail thieves were back at it. Mail theft spiked once more between 1922 and 1926.

Potential robbers and gangsters apparently sought out easier targets once the Marine Corps deployed to guard the U.S. mail. By the end of 1921, the robberies of post offices, USPS train cars, and even individual mail carriers had ceased. The last Marines on mail guard duty ended their tours in March 1922, and the mail seemed safe. But that wasn't the end of violent crime sprees in America. Before the year was out, mail thieves were back at it. Mail theft spiked once more between 1922 and 1926.

"When our men go as guards over the mail," Denby said, "That mail must be delivered, or there must be a Marine dead at the post of duty. There can be no compromise."

In 1926, there was a new President, but President Calvin Coolidge's solution was the same as his predecessor's. When the mail was threatened, the Marine Corps was the go-to law enforcement agency. That year, he deployed more than 1,850 Marines to at-risk mail centers and railways, with another 650 on standby, ready to go where they were needed. The mail robberies stopped once again.

Have you ever wondered why the military gives harmless sounding nicknames to its operations? I've always suspected it's for two reasons: to lull the participants into a false sense of security ("Hey, guys, we get to go on Operation Benign Puppy!"); and to help the bean counters sort out the post-action statistics and costs ("Yes, Senator, we had 95% casualties on Operation Benign Puppy and the cost ran us 1.375 billion dollars)."

In the summer of 1962, we were ordered to participate in Operation Dominic (Hey, guys, we get to participate in Operation Dominic)! Dominic, a Pacific Ocean operation, involved nuclear weapons testing in the vicinity of British owned Christmas Island, for air dropped weapons, and U.S. owned Johnston Atoll for the ambitious, first-time-ever nuclear blast in the earth's outer atmosphere.

In the summer of 1962, we were ordered to participate in Operation Dominic (Hey, guys, we get to participate in Operation Dominic)! Dominic, a Pacific Ocean operation, involved nuclear weapons testing in the vicinity of British owned Christmas Island, for air dropped weapons, and U.S. owned Johnston Atoll for the ambitious, first-time-ever nuclear blast in the earth's outer atmosphere.

My ship was one of several assigned to the scientific element of the operation, which meant we were loaded with instrumented vans, arrayed with a variety of antennas, and directed to steam around beneath the nuclear burst. The nuclear weapon was to be carried aloft on a rocket launched from Johnston Atoll. As D-day and H-hour approached, the anxiety level aboard ship increased noticeably. The major danger, we were told, would not be from the nuclear explosion but from the barrage of instrumented Nike missiles that would be launched to take readings on the detonation. The impact points for these missiles were unpredictable. (I shot a Nike in the air, and where it fell…) Heavy steel I-beams were stacked on top of the instrumented vans to minimize damage should one or more of these unguided missiles land on us. We un-instrumented people were issued helmets.

As launch time approached, the ship went to General Quarters (battle stations), which put me in the unprotected after-gun tub. The uniform for guys about to witness e=mc squared up close and personal was: long-sleeve khaki shirt, buttoned at the neck and wrists; steel helmet (not as reassuring as an I-beam, but what the heck); and 3.5 density goggles, which, during hours of darkness, rendered you completely sightless. The countdown for missile launch proceeded without a hitch, and we watched the rocket with its lethal load (the physics package, as the euphemists have now dubbed it) ride its flame towards a destination above Johnston.

As the countdown for the burst was broadcast over the ship's speaker system, we were directed to don the goggles, close our eyes, and dir ect our faces down and away from the impending burst. In spite of these measures, the light at detonation was as intense as a strobe and was seen 800 miles away in Hawaii. Immediately after the detonation, with goggles removed, I saw a blood-red sky from horizon to horizon, with multiple yellow striations crisscrossing the night sky as small iron rods, which were released by the burst, aligned themselves with the magnetic lines of force around the earth. What an awesome physics lesson!

ect our faces down and away from the impending burst. In spite of these measures, the light at detonation was as intense as a strobe and was seen 800 miles away in Hawaii. Immediately after the detonation, with goggles removed, I saw a blood-red sky from horizon to horizon, with multiple yellow striations crisscrossing the night sky as small iron rods, which were released by the burst, aligned themselves with the magnetic lines of force around the earth. What an awesome physics lesson!

To my knowledge, Dominic had no casualties for the bean counters to summarize; the dollar costs, of course, were enormous. We "survivors" of the first and hopefully last outer atmosphere nuclear weapons test went on about our military business with no ill effects. Our medical records were flagged, and for several years, the results of my annual physical received special scrutiny. The visual effects of that event are firmly imprinted on my mind even today, but when I try to recapture my thoughts as I gazed up into that blood-red sky, the only thing I recall thinking was…I wonder where those Nike missiles are...

It has allowed me to recognize and pay tribute to my family members who have served in the Military.

Sgt Geoffrey W. Reijonen, US Army Veteran

Served 1961-1964

I served as an Officer with the USAFE for four years, from 1966 to 1970. I genuinely enjoyed my four years with the USAF. However, there was one day during that period when my life was put in jeopardy.

I was stationed in Okinawa, and due to my AFSC (job code) as the Officer's Club Manager, I knew all the junior officers. Six of my young fellow officers and I decided to visit Bangkok. With that in mind, we contacted Base Ops, who organized the trip.

I was stationed in Okinawa, and due to my AFSC (job code) as the Officer's Club Manager, I knew all the junior officers. Six of my young fellow officers and I decided to visit Bangkok. With that in mind, we contacted Base Ops, who organized the trip.

The first leg of the trip was a pleasant surprise, at least at the outset. We flew from Okinawa on a large commercial airline. (Boeing 707) World Airways contracted with DoD to provide movement of troops in the Viet Nam theater of operations.

We enjoyed the first leg of the trip until we were about to land in Saigon. The flight captain got on the P.A. system and announced that we would land at Saigon International in about eight minutes. He explained that he would be making a very steep descent into the airfield in compliance with established protocols for landing at this airport. He assured us that this procedure was standard and that the plane was functioning correctly. This vast aircraft put its nose down at a frightening angle two seconds later. Every one of the one hundred or so passengers was white knuckled, grabbing the armrests during this. I could imagine the plane 'staling' out at such a steep descent.

After 5 minutes of terror, the plane leveled out, and one minute later, we landed at Saigon. We noticed as we walked to the terminal that there were many jeeps patrolling the airport's perimeter. They all had machine guns mounted on the back and a gunner riding in the back ready to fire at any sign of trouble. We learned later at Base Ops that the Viet Cong always hung out around the airport and tried to shoot down arriving planes. That explained the bizarre landing that we experienced.

The next leg of our trip was far less comfortable and far more dangerous. We were loaded onto a C130 USAF plane. The seating was a metal bar with plastic webbing, and the C130 is one incredibly noisy airplane. To make matters worse, they were two short of earplugs. Another Lieutenant and I volunteered to do without (what a mistake). We were also crowded around many wooden cases of supplies.

The next leg of our trip was far less comfortable and far more dangerous. We were loaded onto a C130 USAF plane. The seating was a metal bar with plastic webbing, and the C130 is one incredibly noisy airplane. To make matters worse, they were two short of earplugs. Another Lieutenant and I volunteered to do without (what a mistake). We were also crowded around many wooden cases of supplies.

We were heading to Pleiku, the country's northernmost base. The DMZ was only a few miles away.

About halfway through the trip, the co-pilot came out where we were seated and threw open the plane's side door. That put us closer to the turboprop engines, and the sound went from bad to unbearable. He commenced firing a rifle down to the jungle. When he finally shut the door, someone asked him what that was all about. He explained the Viet Cong on the ground firing at our plane and using RPGs (rocket-powered grenades. He also explained why they were so determined to bring us down. He pointed to the crates and explained that was their real target. Upon closer examination of the crates, we could see the stenciled lettering. All those crates were ammunition. Yikes!

We finally landed at Pleiku Air Base. It was not much of a base. It was nearly all Quonset huts. We went into the Officer's Club, and we all got beers. To say the least, it was swelteringly hot.

We had not been there for ten minutes, and an air raid siren went off. Being 'city slickers', the local guys pulled us out of the 'O' Club and directed us into dirt trenches around the base's perimeter. To me, it was just like a WWII movie. I somehow imagined a much more sophisticated approach to bomb shelters. Fortunately, no one was killed by the enemy plane attack. However, one building was destroyed.

We finally arrived at our ultimate destination (Utapoe Air Base) outside Bangkok. All seven of us were exhausted and not in a party mood. Thus ends the saga of my first Vietnam adventure.

“The Gunner and the Grunt” is a unique Vietnam War memoir because it’s actually two memoirs. Two men from Massachusetts join the Army to do very different jobs, train for those jobs, and both go to Vietnam to serve their country. The book is written in two distinct voices, both members of the same reconnaissance unit, the 1st Cavalry Division, providing two very different perspectives of the war. One flies an armed helicopter above, while the other pounds the ground through the jungles below.

“The Gunner and the Grunt” is a unique Vietnam War memoir because it’s actually two memoirs. Two men from Massachusetts join the Army to do very different jobs, train for those jobs, and both go to Vietnam to serve their country. The book is written in two distinct voices, both members of the same reconnaissance unit, the 1st Cavalry Division, providing two very different perspectives of the war. One flies an armed helicopter above, while the other pounds the ground through the jungles below.

The “Gunner” is Michael L. Kelley, who grew up in Boston's Cambridge and Somerville areas. He joined the Army in 1964 and served on active duty through 1967. He became a federal employee and joined the Army Reserve, where he retired as a Master Sergeant in 1990.

Peter Burbank, the titular “Grunt,” was raised in Hull, Massachusetts, just a short drive away from Boston. He grew up reading about small unit actions in World War II, dreaming about becoming an airborne infantry soldier. Joining the Army to fight in Vietnam was something of a lifelong dream for him. He would serve two combat tours before coming back to the real world and becoming a police officer in Portland, Maine. Burbank would also join the Army Reserve, where he spent another 20 years.

The book is a unique piece of personal history, not only because it shares perspectives between the two “boys from Boston” but also because of the time period. The 1st Cavalry Division was the first of two full divisions to deploy to Vietnam, and the airmobile concept was a new tactic. Deploying in 1965, Kelley and Burbank provide a firsthand account of what it was like to fight an entirely new kind of warfare.

Kelley struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder as he worked to write “The Gunner and the Grunt” over the years. He also consulted with fellow cavalry veterans of the war to share memories and get more information. The end result is something truly unique and personal. Veterans will relish the memories it evokes, and even those who never joined the military will find themselves engrossed.

For any veteran thinking of writing their story, Kelley also shares his thoughts about writing as a veteran in the acknowledgments:

“To those readers who like this book, I want to thank you for learning about a soldier’s life in the Vietnam War. I grew up on books about World War II and Korean War Veterans, and I hope there is a younger generation out there who will read about the veterans of the Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq Wars.”

“The Gunner and the Grunt: Two Boston Boys in Vietnam with the First Cavalry Division Airmobile" is available at Amazon and Barnes and Noble. It’s available in hardcover, ebook, and audiobook starting at $20.95.

One of those losses was SFC Paul Ray Smith, a veteran of both the first Gulf War and the Kosovo War. In April 2003, Smith was leading the men of B Company, 11th Engineer Battalion, 3rd Infantry Division, to capture the international airport in Baghdad. While blocking the highway between the city and the airport, he found himself in a crossfire between counterattacking Iraqi forces. Unable to withdraw, he fought against overwhelming odds, giving his life to prevent an aid station from being overrun.

One of those losses was SFC Paul Ray Smith, a veteran of both the first Gulf War and the Kosovo War. In April 2003, Smith was leading the men of B Company, 11th Engineer Battalion, 3rd Infantry Division, to capture the international airport in Baghdad. While blocking the highway between the city and the airport, he found himself in a crossfire between counterattacking Iraqi forces. Unable to withdraw, he fought against overwhelming odds, giving his life to prevent an aid station from being overrun.  With his platoon leader out on patrol, Smith was assigned to create an enemy POW holding area from one of the walled compounds that dotted the highway. The compound's watchtower would provide oversight for the guards manning the POW area.

With his platoon leader out on patrol, Smith was assigned to create an enemy POW holding area from one of the walled compounds that dotted the highway. The compound's watchtower would provide oversight for the guards manning the POW area.  After the Bradley took direct hits from an RPG and was running low on ammunition, the lead APC took a direct hit from an Iraqi mortar, wounding the three crewmen inside. As the Bradley withdrew to reload, he ordered one of his soldiers to back it into the courtyard and manned the APC's .50-cal. amid a withering crossfire from the front and from the towers. He told the other soldier with him to "feed me ammunition whenever you hear the gun get quiet."

After the Bradley took direct hits from an RPG and was running low on ammunition, the lead APC took a direct hit from an Iraqi mortar, wounding the three crewmen inside. As the Bradley withdrew to reload, he ordered one of his soldiers to back it into the courtyard and manned the APC's .50-cal. amid a withering crossfire from the front and from the towers. He told the other soldier with him to "feed me ammunition whenever you hear the gun get quiet."

After its 1777 loss at the Battle of Saratoga, the British Army's strategy to put down the colonial rebellion refocused on the south, where support for the mother country was strongest. Although the campaign itself was more successful than in the north, the British under Lord Cornwallis still suffered some heavy defeats. American militia held their ground at Cowpens, and the collapsing British lost a quarter of their overall strength in the southern colonies. Focused solely on destroying American Nathaniel Greene's Army, Cornwallis burned his baggage train, taking only his wounded warfighting necessities: ammunition, medical supplies, and salt.

After its 1777 loss at the Battle of Saratoga, the British Army's strategy to put down the colonial rebellion refocused on the south, where support for the mother country was strongest. Although the campaign itself was more successful than in the north, the British under Lord Cornwallis still suffered some heavy defeats. American militia held their ground at Cowpens, and the collapsing British lost a quarter of their overall strength in the southern colonies. Focused solely on destroying American Nathaniel Greene's Army, Cornwallis burned his baggage train, taking only his wounded warfighting necessities: ammunition, medical supplies, and salt. Greene's second line was made up of Virginians, who put up a stiff resistance to the incoming British. But the desperate British infantry attacking on all sides soon overwhelmed them, and they too were forced to retreat. Greene's defense in depth was falling apart, but so was the British organization. The redcoats were fragmented as they hit the third line of defense. Their first assault was pushed back by a joint force of Virginians and Marylanders. The Marylanders folded when the British advanced the second time but were pushed back in a colonial counterattack.

Greene's second line was made up of Virginians, who put up a stiff resistance to the incoming British. But the desperate British infantry attacking on all sides soon overwhelmed them, and they too were forced to retreat. Greene's defense in depth was falling apart, but so was the British organization. The redcoats were fragmented as they hit the third line of defense. Their first assault was pushed back by a joint force of Virginians and Marylanders. The Marylanders folded when the British advanced the second time but were pushed back in a colonial counterattack.

The men of that battalion came from the 77th Division, made up mostly of men from New York City. During the allied push, they fought their way into the dense Argonne Forest, where a counterattack soon left them surrounded and cut off from friendly lines. Thinking the unit had been lost, allied artillery shelled their position while German troops repeatedly attacked them from all sides. When word finally got to the allied command, an entire division was sent to relieve them – but would they make it in time?

The men of that battalion came from the 77th Division, made up mostly of men from New York City. During the allied push, they fought their way into the dense Argonne Forest, where a counterattack soon left them surrounded and cut off from friendly lines. Thinking the unit had been lost, allied artillery shelled their position while German troops repeatedly attacked them from all sides. When word finally got to the allied command, an entire division was sent to relieve them – but would they make it in time? The 77th began to dig in, with the hill next to them and the ravine below them occupied by the enemy. That same afternoon, the Germans attacked them from all sides of the hill. Mortars, grenades, and snipers tried to dislodge the Americans, but Whittlesey stayed put. He sent out runners to make contact with French or American units, but no one ever returned. The only consolation was that the Germans took as many casualties as they did. As if that wasn't bad enough, they were taking artillery fire from their own side.

The 77th began to dig in, with the hill next to them and the ravine below them occupied by the enemy. That same afternoon, the Germans attacked them from all sides of the hill. Mortars, grenades, and snipers tried to dislodge the Americans, but Whittlesey stayed put. He sent out runners to make contact with French or American units, but no one ever returned. The only consolation was that the Germans took as many casualties as they did. As if that wasn't bad enough, they were taking artillery fire from their own side.  When news of the situation reached the American Expeditionary Force headquarters, Gen. John J. Pershing sent the 28th Infantry Division, reinforced by the 82nd Infantry Division and the 1st Infantry Division, all under the command of Gen. Hunter Liggett, to relieve them.

When news of the situation reached the American Expeditionary Force headquarters, Gen. John J. Pershing sent the 28th Infantry Division, reinforced by the 82nd Infantry Division and the 1st Infantry Division, all under the command of Gen. Hunter Liggett, to relieve them.

A submarine carrying the name USS Halibut has seen service under three designations. USS Halibut I (a Gato-class boat (SS-232) from 1942-45) was the first vessel of the United States Navy to be named for the halibut, a large, up to 500-pound species of flatfish typically found at the bottom of relatively shallow waters in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Of the original WWII Halibut, Commander Graham C. Scarbro (USN) poignantly wrote, "The Gato-class submarine USS Halibut (SS-232) slid through the waters of the Luzon Strait, prowling for Japanese surface vessels." As the sun rose over her stern on 14 November 1944, her skipper, Lieutenant Commander Ignatius J. "Pete" Galantin, ordered the boat to dive. Increased aerial traffic observed during the night was a promising sign that the Halibut was in the right place. Galantin had a hunch that Japanese shipping, bound to reinforce or resupply beleaguered enemy troops in the Philippines, would soon pass through the Bashi Channel at the north end of the strait.

A submarine carrying the name USS Halibut has seen service under three designations. USS Halibut I (a Gato-class boat (SS-232) from 1942-45) was the first vessel of the United States Navy to be named for the halibut, a large, up to 500-pound species of flatfish typically found at the bottom of relatively shallow waters in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Of the original WWII Halibut, Commander Graham C. Scarbro (USN) poignantly wrote, "The Gato-class submarine USS Halibut (SS-232) slid through the waters of the Luzon Strait, prowling for Japanese surface vessels." As the sun rose over her stern on 14 November 1944, her skipper, Lieutenant Commander Ignatius J. "Pete" Galantin, ordered the boat to dive. Increased aerial traffic observed during the night was a promising sign that the Halibut was in the right place. Galantin had a hunch that Japanese shipping, bound to reinforce or resupply beleaguered enemy troops in the Philippines, would soon pass through the Bashi Channel at the north end of the strait. From 1960-76, there was the USS Halibut II (SSGN-587), built at Mare Island and commissioned on 4 Jan. It was converted to an Attack Submarine at Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard from 6 Feb 1965 to 6 Sep 1965 and redesignated (SSN-587) on 8 Aug 1965. It displaced 3.655 tons (5,000 tons submerged) at a length of 350 feet with a beam of 29 feet. The vessel’s complement was 9-10 officers and 88 enlisted. Its armament consisted of one Regulus I missile launcher, and Halibut could carry five in the hangar. In addition, it had six 21" torpedo tubes (4 forward & 2 aft). It was powered by the S3G nuclear reactor with twin 5-bladed propellers and had been awarded two Presidential Unit Citations, two (or possibly three) Navy Unit Commendations, the Navy E ribbon, and the National Defense Service Medal.

From 1960-76, there was the USS Halibut II (SSGN-587), built at Mare Island and commissioned on 4 Jan. It was converted to an Attack Submarine at Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard from 6 Feb 1965 to 6 Sep 1965 and redesignated (SSN-587) on 8 Aug 1965. It displaced 3.655 tons (5,000 tons submerged) at a length of 350 feet with a beam of 29 feet. The vessel’s complement was 9-10 officers and 88 enlisted. Its armament consisted of one Regulus I missile launcher, and Halibut could carry five in the hangar. In addition, it had six 21" torpedo tubes (4 forward & 2 aft). It was powered by the S3G nuclear reactor with twin 5-bladed propellers and had been awarded two Presidential Unit Citations, two (or possibly three) Navy Unit Commendations, the Navy E ribbon, and the National Defense Service Medal.  ucted with the German V-1 missile at NAS Point Mugu in California. Its barrel-shaped fuselage resembled that of numerous fighter aircraft designs of the post-WWII era, but without a cockpit. When the missiles were deployed, they were launched from a rail launcher and equipped with a pair of Aerojet JATO bottles on the aft end of the fuselage. Halibut, with its extremely large internal hangar, could carry five missiles and was intended to be the prototype of a whole new class of cruise missile-firing SSG-N submarines. Despite being the U.S. Navy's first underwater nuclear capability, the Regulus missile system had significant operational drawbacks. In order to launch, the submarine had to surface and assemble the missile in whatever sea conditions it was in. "Because it required active radar guidance, which only had a range of 225 nmi (259 mi; 417 km), the ship had to stay stationary on the surface to guide it to the target while effectively broadcasting its location. This guidance method was susceptible to jamming, and since the missile was subsonic, the launch platform remained exposed and vulnerable to attack during its flight duration; destroying the ship would effectively disable the missile in flight." A second-generation supersonic Vought SSM-N-9 Regulus II cruise missile with a range of 1,200 nautical miles (2,200 km) and a speed of Mach 2 was developed and successfully tested, including a test launch from Halibut’s sister, the Grayback, but the program was canceled in favor of the UGM-27 Polaris nuclear ballistic missile. Both Regulus I and Regulus II were used as target drones after 1964.

ucted with the German V-1 missile at NAS Point Mugu in California. Its barrel-shaped fuselage resembled that of numerous fighter aircraft designs of the post-WWII era, but without a cockpit. When the missiles were deployed, they were launched from a rail launcher and equipped with a pair of Aerojet JATO bottles on the aft end of the fuselage. Halibut, with its extremely large internal hangar, could carry five missiles and was intended to be the prototype of a whole new class of cruise missile-firing SSG-N submarines. Despite being the U.S. Navy's first underwater nuclear capability, the Regulus missile system had significant operational drawbacks. In order to launch, the submarine had to surface and assemble the missile in whatever sea conditions it was in. "Because it required active radar guidance, which only had a range of 225 nmi (259 mi; 417 km), the ship had to stay stationary on the surface to guide it to the target while effectively broadcasting its location. This guidance method was susceptible to jamming, and since the missile was subsonic, the launch platform remained exposed and vulnerable to attack during its flight duration; destroying the ship would effectively disable the missile in flight." A second-generation supersonic Vought SSM-N-9 Regulus II cruise missile with a range of 1,200 nautical miles (2,200 km) and a speed of Mach 2 was developed and successfully tested, including a test launch from Halibut’s sister, the Grayback, but the program was canceled in favor of the UGM-27 Polaris nuclear ballistic missile. Both Regulus I and Regulus II were used as target drones after 1964.  According to the documentary Regulus: The First Nuclear Missile Submarines, the primary target for Halibut in the event of a nuclear exchange would be to eliminate the Soviet naval base at Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. The patrols made by Halibut and its sister Regulus-firing submarines represented the first ever deterrent patrols in the history of the submarine navy, preceding those made by the Polaris missile-firing submarines. Halibut was used in underwater espionage missions by the US against the Soviet Union. Her most notable accomplishments included:

According to the documentary Regulus: The First Nuclear Missile Submarines, the primary target for Halibut in the event of a nuclear exchange would be to eliminate the Soviet naval base at Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. The patrols made by Halibut and its sister Regulus-firing submarines represented the first ever deterrent patrols in the history of the submarine navy, preceding those made by the Polaris missile-firing submarines. Halibut was used in underwater espionage missions by the US against the Soviet Union. Her most notable accomplishments included:

Between 1920 and 1921 alone, thieves stole an estimated $86 million (adjusted for inflation) over 36 robberies of the U.S. Postal Service. With 250,000 miles of postal railway, adequately guarding the mail was nearly impossible for just 500 postal inspectors. What could the government do to protect the mail?

Between 1920 and 1921 alone, thieves stole an estimated $86 million (adjusted for inflation) over 36 robberies of the U.S. Postal Service. With 250,000 miles of postal railway, adequately guarding the mail was nearly impossible for just 500 postal inspectors. What could the government do to protect the mail?  "To the Men of the Mail Guard, you must, when on guard duty, keep your weapons in hand and, if attacked, shoot and shoot to kill," Denby said. "If two Marines are covered by a robber, neither must put up his hands, but both must immediately go for their guns. One may die, but the other will get the robber, and the mail will get through."

"To the Men of the Mail Guard, you must, when on guard duty, keep your weapons in hand and, if attacked, shoot and shoot to kill," Denby said. "If two Marines are covered by a robber, neither must put up his hands, but both must immediately go for their guns. One may die, but the other will get the robber, and the mail will get through." Potential robbers and gangsters apparently sought out easier targets once the Marine Corps deployed to guard the U.S. mail. By the end of 1921, the robberies of post offices, USPS train cars, and even individual mail carriers had ceased. The last Marines on mail guard duty ended their tours in March 1922, and the mail seemed safe. But that wasn't the end of violent crime sprees in America. Before the year was out, mail thieves were back at it. Mail theft spiked once more between 1922 and 1926.

Potential robbers and gangsters apparently sought out easier targets once the Marine Corps deployed to guard the U.S. mail. By the end of 1921, the robberies of post offices, USPS train cars, and even individual mail carriers had ceased. The last Marines on mail guard duty ended their tours in March 1922, and the mail seemed safe. But that wasn't the end of violent crime sprees in America. Before the year was out, mail thieves were back at it. Mail theft spiked once more between 1922 and 1926.

In the summer of 1962, we were ordered to participate in Operation Dominic (Hey, guys, we get to participate in Operation Dominic)! Dominic, a Pacific Ocean operation, involved nuclear weapons testing in the vicinity of British owned Christmas Island, for air dropped weapons, and U.S. owned Johnston Atoll for the ambitious, first-time-ever nuclear blast in the earth's outer atmosphere.

In the summer of 1962, we were ordered to participate in Operation Dominic (Hey, guys, we get to participate in Operation Dominic)! Dominic, a Pacific Ocean operation, involved nuclear weapons testing in the vicinity of British owned Christmas Island, for air dropped weapons, and U.S. owned Johnston Atoll for the ambitious, first-time-ever nuclear blast in the earth's outer atmosphere. ect our faces down and away from the impending burst. In spite of these measures, the light at detonation was as intense as a strobe and was seen 800 miles away in Hawaii. Immediately after the detonation, with goggles removed, I saw a blood-red sky from horizon to horizon, with multiple yellow striations crisscrossing the night sky as small iron rods, which were released by the burst, aligned themselves with the magnetic lines of force around the earth. What an awesome physics lesson!

ect our faces down and away from the impending burst. In spite of these measures, the light at detonation was as intense as a strobe and was seen 800 miles away in Hawaii. Immediately after the detonation, with goggles removed, I saw a blood-red sky from horizon to horizon, with multiple yellow striations crisscrossing the night sky as small iron rods, which were released by the burst, aligned themselves with the magnetic lines of force around the earth. What an awesome physics lesson!

I was stationed in Okinawa, and due to my AFSC (job code) as the Officer's Club Manager, I knew all the junior officers. Six of my young fellow officers and I decided to visit Bangkok. With that in mind, we contacted Base Ops, who organized the trip.

I was stationed in Okinawa, and due to my AFSC (job code) as the Officer's Club Manager, I knew all the junior officers. Six of my young fellow officers and I decided to visit Bangkok. With that in mind, we contacted Base Ops, who organized the trip. The next leg of our trip was far less comfortable and far more dangerous. We were loaded onto a C130 USAF plane. The seating was a metal bar with plastic webbing, and the C130 is one incredibly noisy airplane. To make matters worse, they were two short of earplugs. Another Lieutenant and I volunteered to do without (what a mistake). We were also crowded around many wooden cases of supplies.

The next leg of our trip was far less comfortable and far more dangerous. We were loaded onto a C130 USAF plane. The seating was a metal bar with plastic webbing, and the C130 is one incredibly noisy airplane. To make matters worse, they were two short of earplugs. Another Lieutenant and I volunteered to do without (what a mistake). We were also crowded around many wooden cases of supplies.

“The Gunner and the Grunt” is a unique Vietnam War memoir because it’s actually two memoirs. Two men from Massachusetts join the Army to do very different jobs, train for those jobs, and both go to Vietnam to serve their country. The book is written in two distinct voices, both members of the same reconnaissance unit, the 1st Cavalry Division, providing two very different perspectives of the war. One flies an armed helicopter above, while the other pounds the ground through the jungles below.

“The Gunner and the Grunt” is a unique Vietnam War memoir because it’s actually two memoirs. Two men from Massachusetts join the Army to do very different jobs, train for those jobs, and both go to Vietnam to serve their country. The book is written in two distinct voices, both members of the same reconnaissance unit, the 1st Cavalry Division, providing two very different perspectives of the war. One flies an armed helicopter above, while the other pounds the ground through the jungles below.