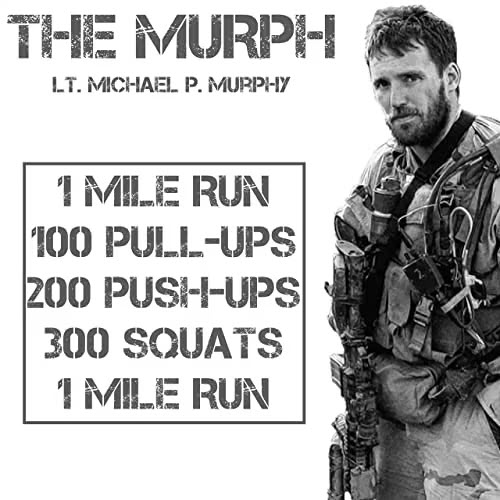

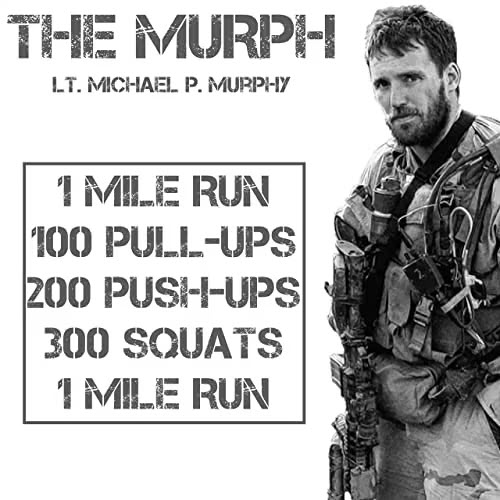

Whether you're a fitness enthusiast or not, you might have heard about "The Murph Challenge." Every Memorial Day, veterans, military members, and fitness nuts around the country pledge to take the challenge. It not only helps remember the courage and sacrifice of Navy SEAL Lt. Michael P. Murphy, but also helps send military-connected individuals to college through the Lt. Michael P. Murphy Memorial Scholarship Foundation.

To call the Murph a "grueling" workout would be an understatement, but it was something he did regularly, and it helped him fight on in the mountains of Afghanistan against incredible odds. Without his valiant physical and mental efforts that day, his entire team might have vanished without a trace.

To call the Murph a "grueling" workout would be an understatement, but it was something he did regularly, and it helped him fight on in the mountains of Afghanistan against incredible odds. Without his valiant physical and mental efforts that day, his entire team might have vanished without a trace.

In 2005, the U.S. launched Operation Red Wings in Afghanistan's Kunar Province. The goal was to disrupt the activity of the Taliban and other anti-Coalition militias operating in the areas west of Asadabad. The local anti-Coalition fighters were led by Ahmad Shah, who was in charge of a relatively small band and based his operations on a mountain called Sawtalo Sar near Asadabad. His posts were said to be just outside of a village on the high slopes of the mountain. Once the SEAL reconnaissance team confirmed that Shah was at these buildings, they would call in a SEAL strike team and Marines to capture or kill Shah.

Operation Red Wings was, of course, much bigger than just that initial capture of an insurgent leader, but that was the SEALs' mission when a four-man team fast-roped into the area near the Sawtalo Sar. Murphy led Petty Officer Second Class Danny Dietz, Petty Officer Second Class Matthew G. Axelson, and Hospital Corpsman Second Class Marcus Luttrell into the area 1.5 miles away from their first target. They then moved into an overwatch position.

And that's where everything went sideways.

Some goat herders happened to stumble upon the SEALs' hideout spot. They were detained but when Murphy determined they weren't enemy combatants and actually were goat herders and thus not legitimate targets, he set them free in accordance with the laws of armed conflict. Knowing full well the herdsmen would report the SEALs to their local militia leaders, likely Shah himself, the Americans decided to retreat. They didn't make it far enough, fast enough, because it wasn't long before Afghan militia fighters were on them with small arms, machine guns, mortars, and RPGs. The heavy, intense enemy fire forced the SEALs into a gulch on the far side of the mountain, making communication nearly impossible.

Some goat herders happened to stumble upon the SEALs' hideout spot. They were detained but when Murphy determined they weren't enemy combatants and actually were goat herders and thus not legitimate targets, he set them free in accordance with the laws of armed conflict. Knowing full well the herdsmen would report the SEALs to their local militia leaders, likely Shah himself, the Americans decided to retreat. They didn't make it far enough, fast enough, because it wasn't long before Afghan militia fighters were on them with small arms, machine guns, mortars, and RPGs. The heavy, intense enemy fire forced the SEALs into a gulch on the far side of the mountain, making communication nearly impossible.

Outnumbered 10-to-1, Murphy and the SEALs did not back down, and all of them were eventually wounded over the course of the two-hour fight. When Dietz, the communications operator, was shot in the hand, Murphy picked up the radio and satellite phone, trying desperately to connect with Coalition forces. When he realized the terrain was the problem, he fought his way to an open area devoid of cover or concealment amid a fierce firefight so he could give his location and ask for help from the Quick Reaction Force at Bagram Air Base.

Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison was notorious long before U.S. troops were found guilty of abusing detainees there. Originally built in the 1960s, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein used the site to house and later execute political prisoners. He closed the prison in 2002, but when the U.S.-led Coalition ousted Hussein by force in 2003, it was reopened. Because Coalition forces used it as an internment camp, it also became a forward operating base – and a target for insurgents.

Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison was notorious long before U.S. troops were found guilty of abusing detainees there. Originally built in the 1960s, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein used the site to house and later execute political prisoners. He closed the prison in 2002, but when the U.S.-led Coalition ousted Hussein by force in 2003, it was reopened. Because Coalition forces used it as an internment camp, it also became a forward operating base – and a target for insurgents.

Insurgent battles in Iraq don't always get their due attention from historians, but for the longest time, the biggest obstacle to American success in the Iraq War was these insurgent groups. Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq, was one of the architects of Iraq's Sunni insurgency. Determined to hit the Abu Ghraib base to show that nowhere in the country was safe as long as the Americans were in control, he launched an attack on Abu Ghraib so effective and complex that it shocked the defenders of the FOB and American leadership in the country. It was the first time al-Qaeda in Iraq directly attacked the U.S. military.

The plan was surprisingly sophisticated. At about an hour after sunset on April 2, 2005, a large number of insurgent fighters fired small arms, rocket-propelled grenades, and mortars at strategic points inside the Abu Ghraib complex. While the American defenders inside scrambled to see where the attacks were coming from and mount a defense, a Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Device – or VBIED, Iraq War parlance for a large car bomb – drove toward the walls of the base, to blow a hole in the compound, creating a breach for insurgents to exploit.

The plan was surprisingly sophisticated. At about an hour after sunset on April 2, 2005, a large number of insurgent fighters fired small arms, rocket-propelled grenades, and mortars at strategic points inside the Abu Ghraib complex. While the American defenders inside scrambled to see where the attacks were coming from and mount a defense, a Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Device – or VBIED, Iraq War parlance for a large car bomb – drove toward the walls of the base, to blow a hole in the compound, creating a breach for insurgents to exploit.

Every part of the American base came under attack at once as the car bomb drove toward Abu Ghraib. Although the Marines couldn't make out exactly how many enemy fighters were taking part in the assault, some estimated as low as 60 and as many as 300, given the intensity of the small arms and RPGs being fired at the towers overlooking the wall defenses. Luckily, the Marines' own small arms fire hit the car bomb as it sped away, causing the explosives to detonate some 100 meters before reaching the wall.

Although the firefight  appeared to be happening in every direction at the same time, the attack was more concerted than it seemed. The defenses took a lot of fire from a field to the east, but that attack was a diversion. The main effort for the insurgents focused on Tower 4, along one of Abu Ghraib's southern corners. The Americans may not have realized how critical that tower was to the enemy's plan, but when the car bomb failed to breach the wall, Tower 4 became the best way into the forward operating base. The Marines inside were taking heavy fire and hand grenade attacks as they manned their .50-caliber machine gun.

appeared to be happening in every direction at the same time, the attack was more concerted than it seemed. The defenses took a lot of fire from a field to the east, but that attack was a diversion. The main effort for the insurgents focused on Tower 4, along one of Abu Ghraib's southern corners. The Americans may not have realized how critical that tower was to the enemy's plan, but when the car bomb failed to breach the wall, Tower 4 became the best way into the forward operating base. The Marines inside were taking heavy fire and hand grenade attacks as they manned their .50-caliber machine gun.

In another tower, hand grenades and RPGs forced the defending Marines to withdraw, rappelling down the tower and reforming a perimeter inside the walls of Abu Ghraib with a machine gun. Had the vehicle hit the walls of the compound or the insurgents focused on entering by way of another tower, the outcome of the battle might have been very different.

The fighting for Tower 4 was so intense and precisely coordinated that the Marines were certain they would have to hold it by any means necessary, especially once their .50-cal ammunition ran low. Toward the end of the battle, they fixed bayonets in preparation for hand-to-hand combat. Luckily, it wouldn't come to that. The insurgents threw everything they could at the walls, but with no help from the detainees inside and no way to breach the defenses, they were forced to fall back.

After nearly two and a half hours of intense fighting, the defenses at Abu Ghraib held. NBC News reported that insurgents used nine different car bombs or IEDs during the attack, along with more than a hundred mortar rounds and 10,000 rounds of small arms ammunition. American estimates of insurgent casualties numbered more than 70. The Americans had 44 wounded and no one killed in action.

After nearly two and a half hours of intense fighting, the defenses at Abu Ghraib held. NBC News reported that insurgents used nine different car bombs or IEDs during the attack, along with more than a hundred mortar rounds and 10,000 rounds of small arms ammunition. American estimates of insurgent casualties numbered more than 70. The Americans had 44 wounded and no one killed in action.

The attack on Abu Ghraib prison was the most sophisticated and potentially deadly since the end of major combat operations in Iraq in 2003. It was also a harbinger of the destructive and seemingly relentless civil war to come.

Looking back at what I have written brings back so many memories of things that happened almost 60 years ago. It is difficult to impart to the younger generation just what that time meant, as some don't even know what the draft was all about and how it played a part in deciding what a person was going to do with their time—for many, it was their first real job.

SP4 Robert A. Chesebro, Jr, US Army Veteran

Served 1961-1964

There are a lot of military myths and urban legends out there, but few are more widespread or ridiculous than the legend of the base flagpole truck. No one knows who started it or why. It's just a legend that has been passed down from generation to generation of veterans. It transcends military branches and eras of wars, and it is as common to hear the myths of saltpeter in the Gatorade or "etherbunny."

There are a lot of military myths and urban legends out there, but few are more widespread or ridiculous than the legend of the base flagpole truck. No one knows who started it or why. It's just a legend that has been passed down from generation to generation of veterans. It transcends military branches and eras of wars, and it is as common to hear the myths of saltpeter in the Gatorade or "etherbunny."

The legend goes that the truck above every military installation's flagpole is actually hollow and contains three to five very specific items for very specific uses. The most common legend is that it has three items: a razor blade, a match, and a bullet. The razor blade, it's said, is used to strip the flag, the match is to burn the flag properly, and the bullet is to use in defense of yourself (or, in some versions, to use on yourself). In another version of the myth, the truck also contains grains of rice and a penny (or some kind of coin). The rice is for nourishment, and the coin is supposedly to blind the enemy.

Every flagpole has a truck. It's the thing at the top that holds the rope and pulley system in place, so one could easily raise and lower the flag. Some flagpole trucks also have some kind of ornamentation or finial, because flags are usually important things and there's nothing wrong with a little élan. But most of the time it's just a big golden ball, made of solid metal. There is nothing in it, and if there were, I would hope it would be much more useful than a handful of stuff you might find in a kitchen utility drawer.

There are many problems with this specific myth. First, the idea that a permanent American military installation is being overrun is absurd. American troops will call in airstrikes on their own position rather than just let the enemy overrun their fellow soldiers. Secondly, as much as troops love Old Glory, if their base is being overrun, the base flagpole is not a high priority. Finally, imagine how long it would take to bring down the flag and burn it respectfully. Retreating soldiers have better things to do.

There are many problems with this specific myth. First, the idea that a permanent American military installation is being overrun is absurd. American troops will call in airstrikes on their own position rather than just let the enemy overrun their fellow soldiers. Secondly, as much as troops love Old Glory, if their base is being overrun, the base flagpole is not a high priority. Finally, imagine how long it would take to bring down the flag and burn it respectfully. Retreating soldiers have better things to do.

Of all the myths and urban legends I've heard in my time in the military, this one was always especially astonishing because it's the one that makes absolutely zero military sense. It sounds like something an overly patriotic civilian would make up. The simple fact is that U.S. troops fight and don't care about symbolic gestures when someone is trying to kill their buddies. Even in a scenario where a base is being overrun, a retreating U.S. troop might take down the flag, but they wouldn't burn it. They would save it because raising the same flag when we retake our base would be that much more badass.

As for defending a base until the last man, the United States has never needed such a thing. We don't leave our fallen behind, and if we ever did leave them on a base taken by the enemy, the enemy would know for certain that we are coming back for our people. They can keep the flagpole.

"Immense bright lake! I trace in thee

An emblem of the mighty ocean,

And in thy restless waves I see

Nature's eternal law of motion;

And fancy sees the Huron Chief…"

"Lake Huron" by Thomas McQueen

The peninsular state of Michigan (est. 1837) resembles an extended left human hand in a mitt with the thumb partly opened outward from the palm. And there, about where the quick of a thumbnail would be on the east side, is US Coast Guard Station Harbor Beach as it's known today. It is estimated that since the 17th century, there are 6,000 maritime wrecks at the bottom of the mighty Great Lakes, one of which is Lake Huron. District 9, consisting of forty-eight active stations, is a United States Coast Guard area of operations based in Cleveland, Ohio. It is responsible for all Coast Guard functions on the five Great Lakes, the Saint Lawrence Seaway, and surrounding states, accumulating 6,700 miles of shoreline and 1,500 miles of international shoreline with Canada. It includes roughly 6,000 active duty, reserve, and civilian personnel serving duties such as search and rescue, maritime safety and security, environmental protection, maritime law enforcement, aids to navigation, and icebreaking. About sixty miles north of Port Huron, Station Harbor Beach (area pop. 1,604 in 2020) is one of eight USCG facilities in Sector Detroit. Originally named Barnettsville in 1855, the town was settled as a sawmill and shipping port, sending lumber down into and out of the Saginaw riverine system; eventually becoming known as Sand Beach by 1899, which changed again to Harbor Beach (est. 1910). It offers the largest man-made freshwater harbor of refuge to ships traveling between Port Huron and Pointe Aux Barques, against record temperatures between -22 and +95, with snowfall totaling as much as fifty inches, six months of the year.

The peninsular state of Michigan (est. 1837) resembles an extended left human hand in a mitt with the thumb partly opened outward from the palm. And there, about where the quick of a thumbnail would be on the east side, is US Coast Guard Station Harbor Beach as it's known today. It is estimated that since the 17th century, there are 6,000 maritime wrecks at the bottom of the mighty Great Lakes, one of which is Lake Huron. District 9, consisting of forty-eight active stations, is a United States Coast Guard area of operations based in Cleveland, Ohio. It is responsible for all Coast Guard functions on the five Great Lakes, the Saint Lawrence Seaway, and surrounding states, accumulating 6,700 miles of shoreline and 1,500 miles of international shoreline with Canada. It includes roughly 6,000 active duty, reserve, and civilian personnel serving duties such as search and rescue, maritime safety and security, environmental protection, maritime law enforcement, aids to navigation, and icebreaking. About sixty miles north of Port Huron, Station Harbor Beach (area pop. 1,604 in 2020) is one of eight USCG facilities in Sector Detroit. Originally named Barnettsville in 1855, the town was settled as a sawmill and shipping port, sending lumber down into and out of the Saginaw riverine system; eventually becoming known as Sand Beach by 1899, which changed again to Harbor Beach (est. 1910). It offers the largest man-made freshwater harbor of refuge to ships traveling between Port Huron and Pointe Aux Barques, against record temperatures between -22 and +95, with snowfall totaling as much as fifty inches, six months of the year.

Sand Beach was selected in 1872 as the site for an artificial harbor to provide for mariners caught in storms in the southern portion of Lake Huron. Construction commenced in 1873 on a project that provided for a breakwater of stone-filled cribwork to shelter an area of some 650 acres. When completed in 1885 at a cost of $975,000, the breakwater provided the only safe refuge on the western coast of Lake Huron between Tawas Bay and the St. Clair River, a distance of 115 miles. A pierhead light was placed in operation on 25 October 1875 at the angle of the breakwater to mark the structure until the project was complete and additional lights could be built. This first light consisted of a square, open-frame tower surmounted by an octagonal lantern room. A fourth-order lens produced a fixed white light at a focal plane of thirty-five feet. The main light commenced operation on 1 October 1885, and the fog signal followed suit a week later. The town of Sand Beach, justifiably proud of their harbor, changed its name to Harbor Beach, and the cast-iron lighthouse has subsequently been known as Harbor Beach Lighthouse. In 1934, a cable was run from shore to provide commercial power to the lighthouse and fog signal, and a radio beacon was established at the station. The last Coast Guard crew left the lighthouse after the 1967 shipping season, which actually ran until 2 January 1968, and no longer after that, the fog signal building was removed. The tower's Fresnel lens was removed in 1986 and placed on display at the Grice House Museum in Harbor Beach. In 2004, Harbor Beach Lighthouse, deemed excess by the Coast Guard, was offered at no cost to eligible entities under the provisions of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000. Founded in 1898 as the US Coast Guard took over a Lifeboat Station for the US Lifesaving Service, Station Harbor Beach in the 1930s and saw heavy use during the Second World War, training new Coast Guard recruits. The station was closed as a full-time facility in 1973 due to budget restrictions, but it remained operational as a seasonal, summer-only station manned by USCG Auxiliary and Reserve Units. In 2004, Station Harbor Beach was formally re-opened as a full-time, fully crewed station and remains so today as part of the US Coast Guard's 9th District, Sector Detroit.

of their harbor, changed its name to Harbor Beach, and the cast-iron lighthouse has subsequently been known as Harbor Beach Lighthouse. In 1934, a cable was run from shore to provide commercial power to the lighthouse and fog signal, and a radio beacon was established at the station. The last Coast Guard crew left the lighthouse after the 1967 shipping season, which actually ran until 2 January 1968, and no longer after that, the fog signal building was removed. The tower's Fresnel lens was removed in 1986 and placed on display at the Grice House Museum in Harbor Beach. In 2004, Harbor Beach Lighthouse, deemed excess by the Coast Guard, was offered at no cost to eligible entities under the provisions of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000. Founded in 1898 as the US Coast Guard took over a Lifeboat Station for the US Lifesaving Service, Station Harbor Beach in the 1930s and saw heavy use during the Second World War, training new Coast Guard recruits. The station was closed as a full-time facility in 1973 due to budget restrictions, but it remained operational as a seasonal, summer-only station manned by USCG Auxiliary and Reserve Units. In 2004, Station Harbor Beach was formally re-opened as a full-time, fully crewed station and remains so today as part of the US Coast Guard's 9th District, Sector Detroit.

Station (SM) Harbor Beach is responsible for 1,035 square miles of Lake Huron, which encompasses 91 miles of rocky shoreline starting at Wild Fowl Point, in the northwest, and ending in Port Sanilac, to the south. The station was seasonalized [meaning not open in winter] in 2017 and is now a sub-unit of Station Port Huron. It resides within the harbor, leases slips from the city-owned marina, and is responsible for the area from Port Sanilac to Caseville.

The grit and determination of personnel at such remote stations is legendary, as recounted in the following incident which could as easily happen tomorrow there:

"In early October 1888, the St. Clair was one of six barges hauling a load of coal north on Lake Huron. A steamer named the Lowell was towing the barges off the eastern shore of the thumb when the convoy ran into an autumn storm. A strong wind out of the north-northeast and the resulting choppy waves made conditions extremely hazardous for the convoy, and eventually the towline either snapped or was intentionally severed. The Lowell remained in the safety of the harbor, and two of the barges set sail for safer destinations like Port Huron, but the St. Clair, a decommissioned side-wheel steamer, found itself in distress. As the crisis unfolded, members of the US Lifesaving Station at Harbor Beach watched from the shore. A tugboat sitting in the safe waters of the harbor refused to come to the aid of the St. Clair, so Lifesaving Service Capt. George Plough ordered his eight surfmen to suit up and put their lifeboat in the water… With the waves crashing into the breakwall, the lifeboat headed back out toward the St. Clair, which had been brutalized by the storm. Its bow was almost underwater and its crew  was huddled together at the stern, desperately awaiting their rescuers… As the lifeboat headed between the piers, a wave broached the vessel, spinning it violently and throwing its occupants into the lake. Once in the water, they were pulled back and forth from the beach by a backwash created by waves crashing into the shore… The Lifesaving Service district superintendent would write, 'Braver men never manned an oar.' They were met with a hero's welcome when they returned to Harbor Beach, and two of them would go on to become keepers of their own stations. 'They were made of stern stuff,' [marine artist] Robert McGreevy said at the time. The five St. Clair crew members were initially buried together in the Port Sanilac Cemetery in what was described as a pauper's grave. Jones and one of his crew were eventually relocated to their hometown of Bay City. Graveratte, 30-year-old seaman George McFarland of Cleveland and 30-year-old Henry Anderson of Australia remain interred in the cemetery. A large gravestone was later placed at their burial site, adorned with an anchor and bearing an inscription recounting the events of Oct. 1-2, 1888." In 1915, the life-saving service was combined with the United States Revenue Service and became the United States Coast Guard. A Coast Guard Station was built in 1935 at the foot of Pack Street. An earthen causeway was laid out into the lake for a four-bay garage.

was huddled together at the stern, desperately awaiting their rescuers… As the lifeboat headed between the piers, a wave broached the vessel, spinning it violently and throwing its occupants into the lake. Once in the water, they were pulled back and forth from the beach by a backwash created by waves crashing into the shore… The Lifesaving Service district superintendent would write, 'Braver men never manned an oar.' They were met with a hero's welcome when they returned to Harbor Beach, and two of them would go on to become keepers of their own stations. 'They were made of stern stuff,' [marine artist] Robert McGreevy said at the time. The five St. Clair crew members were initially buried together in the Port Sanilac Cemetery in what was described as a pauper's grave. Jones and one of his crew were eventually relocated to their hometown of Bay City. Graveratte, 30-year-old seaman George McFarland of Cleveland and 30-year-old Henry Anderson of Australia remain interred in the cemetery. A large gravestone was later placed at their burial site, adorned with an anchor and bearing an inscription recounting the events of Oct. 1-2, 1888." In 1915, the life-saving service was combined with the United States Revenue Service and became the United States Coast Guard. A Coast Guard Station was built in 1935 at the foot of Pack Street. An earthen causeway was laid out into the lake for a four-bay garage.

The station itself was built 300 yards offshore and connected to the causeway by a walkway. During World War II, the station was used for training and housed 100 Coast Guardsmen.

Coast Guard boats were stored in the rear of the station on a marine railway. When making a rescue, the guardsmen climbed aboard, and the boat slid down the rails into the water. In 1987, the old station was left vacant and fell into disrepair. It was torn down in 2004. The current Coast Guard Station, located north of the Harbor Beach Marina, was built in 1987. The new structure consists of offices, bedrooms, a recreation room, a kitchen, and a communications room. A large boat storage and maintenance building was built in 2008 to complement the station's activities. The search and rescue boats are kept in the Harbor Beach Marina. Harbor Beach is proud to have hosted the life-saving service and the United States Coast Guard continuously since 1881.

Pictured here, the current USCG facility. This is a "sparkplug lighthouse" located at the end of the north breakwall entrance to this harbor of refuge on Lake Huron. Coast Guard TWS lists twelve members who served at this station under its current name, and three who served there when it was called Sand Beach Station; so named owing, as with other variably windward coastal areas of Michigan, to unusually plentiful pure sand deposits and meteorological lake-effect.

Pictured here, the current USCG facility. This is a "sparkplug lighthouse" located at the end of the north breakwall entrance to this harbor of refuge on Lake Huron. Coast Guard TWS lists twelve members who served at this station under its current name, and three who served there when it was called Sand Beach Station; so named owing, as with other variably windward coastal areas of Michigan, to unusually plentiful pure sand deposits and meteorological lake-effect.

It's a fantastic place to connect with your buddies. Memories are coming back.

We've all done crazy things during a night of drinking. For most of us, it was probably a night we would rather forget. However, when you're the President of the United States, it could result in a night that makes the history books. Imagine having to be Henry Kissinger, asking the Joint Chiefs of Staff not to nuke North Korea back to the Stone Age until the Leader of the Free World sobered up the next day.

Everyone is entitled to a drink now and then, especially after a stressful day at work. And there might be few jobs that are as stressful as that of President of the United States (or as dangerous). President Richard M. Nixon was known for his love of bourbon and whiskey and his low tolerance for the stuff. So keep in mind that no one is judging President Nixon for taking a drink. In fact, it might have even helped his anti-Soviet foreign policy.

When hardline anti-communist Nixon took office in 1969, the United States was mired in the Vietnam War, and the new President had campaigned on ending American involvement there. When it came to Foreign Policy, Nixon and his tag team partner Kissinger were experts on another level. To cower the Soviet Union, China and North Vietnam, Nixon came up with a policy that would make communist leaders and their allies believe he was so irrational that he might start a nuclear war at any time.

When hardline anti-communist Nixon took office in 1969, the United States was mired in the Vietnam War, and the new President had campaigned on ending American involvement there. When it came to Foreign Policy, Nixon and his tag team partner Kissinger were experts on another level. To cower the Soviet Union, China and North Vietnam, Nixon came up with a policy that would make communist leaders and their allies believe he was so irrational that he might start a nuclear war at any time.

"I call it the Madman Theory, Bob," he told his Chief of Staff. I want the North Vietnamese to believe I've reached the point where I might do anything to stop the war. We'll just slip the word to them that, 'for God's sake, you know Nixon is obsessed about communism. We can't restrain him when he's angry – and he has his hand on the nuclear button,' and Ho Chi Minh himself will be in Paris in two days begging for peace."

Nixon the Madman didn't really work against the North Vietnamese, but it may have prevented a nuclear exchange between the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union in 1969. When he first took office, however, no one really knew how great Nixon would be as a statesman. One of his first tests came in April 1969, when North Korea shot down an EC-121 spy plane over the Sea of Japan. When Nixon was told about it, he was not only angry about North Korea, but he was ready to go to war with all communists.

At this time, North Korea was at the height of its power but was still protected by the Soviet Union and its missile systems. It was militarily, economically, and industrially stronger than South Korea, but not the U.S. But the U.S. had communist problems elsewhere, too. In Vietnam, the United States was still recovering from the Tet Offensive the previous year. The Soviet Union and communist China were constant thorns in the side of American power. After a few drinks, President Nixon got sick of all of it and put the U.S. military on alert to carry out the SIOP or Single Integrated Operational Plan: the U.S. nuclear strike plan for war with the communists.

At this time, North Korea was at the height of its power but was still protected by the Soviet Union and its missile systems. It was militarily, economically, and industrially stronger than South Korea, but not the U.S. But the U.S. had communist problems elsewhere, too. In Vietnam, the United States was still recovering from the Tet Offensive the previous year. The Soviet Union and communist China were constant thorns in the side of American power. After a few drinks, President Nixon got sick of all of it and put the U.S. military on alert to carry out the SIOP or Single Integrated Operational Plan: the U.S. nuclear strike plan for war with the communists.

When the Joint Chiefs called the White House to ask for possible targets, it was Henry Kissinger who answered the phone and prevented World War III. He convinced the Pentagon to wait until Nixon woke up the next morning, presumably sober, before calling for a strike package. It turns out that President Nixon would routinely order bombing raids on foreign adversaries after a few rounds. Obviously, World War III never came, but it wasn't for lack of giving the Presidential orders.

"If the President had his way," Kissinger growled to aides more than once, "there would be a nuclear war each week!"

I was assigned as the Public Information Officer to the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV), operating in I Corps (My Lai to the DMZ) from September 1971 to Sep 1972. I conducted daily briefings to the press corps on operational activities and the troop drawdown. In that capacity, and also as an accredited MACV Armed Forces Combat Photographer (#0867), I escorted the U.S. and international media throughout the area of operations for that year, assisting their efforts while developing my own photojournalism stories.

I was assigned as the Public Information Officer to the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV), operating in I Corps (My Lai to the DMZ) from September 1971 to Sep 1972. I conducted daily briefings to the press corps on operational activities and the troop drawdown. In that capacity, and also as an accredited MACV Armed Forces Combat Photographer (#0867), I escorted the U.S. and international media throughout the area of operations for that year, assisting their efforts while developing my own photojournalism stories.

My pockets were usually filled with 35mm film canisters. I wore a derby hat, which I could easily roll up and stick in my blouse pocket. The baseball hat's bill and front panels didn't allow for that. I carried most of my other gear in an American Tourister travel bag. This was pre-the backpacks, which are now standard issues. While the Army kept my fatigues in the country, I got out with my jungle boots, which I later wore when assigned to the Multinational Force and Observers in the Sinai some ten years later. Not the best application, but you go with the Army (and equipment) you have (a la Rummy's Statement).

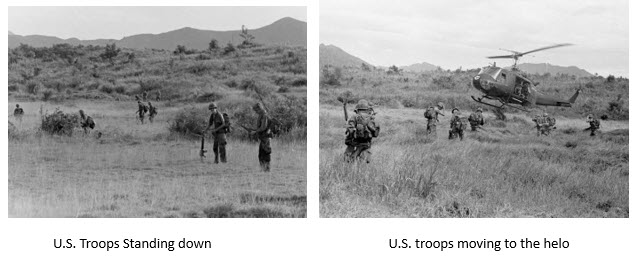

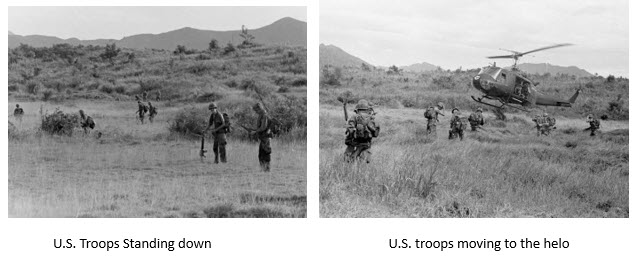

Contrary to popular opinion, the U.S. Army's departure from RVN was orderly, as were other U.S. units before them.

Contrary to popular opinion, the U.S. Army's departure from RVN was orderly, as were other U.S. units before them.

The evacuation of troops in Saigon in 1973 and its later fall in April 1975 occurred long after the U.S. ended formal ground operations.

I mostly took B/W photos so I could develop them in my office's kitchen.

The MACV Observer was produced by the Command Information Division, Office of Information, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, in Saigon.

The MACV publication has been reconstructed in Word. I've added the caption associated with the photo in a column on the left. Notes and comments are provided as appropriate.

U.S. Army Photos by Captain G A Redding

THE COLORS are lowered at the final retreat ceremony on Hill 260 overlooking Da Nang This was the last flag to fly over a U.S. support base in the Republic of Vietnam The ceremony was one of the activities marking the stand down of the 21st Infantry, and attached units – the last of the U.S. forces maneuver battalions in RVN.

THE COLORS are lowered at the final retreat ceremony on Hill 260 overlooking Da Nang This was the last flag to fly over a U.S. support base in the Republic of Vietnam The ceremony was one of the activities marking the stand down of the 21st Infantry, and attached units – the last of the U.S. forces maneuver battalions in RVN.

NOTE: This photo and caption were on the front page of the Observer. The rest of the photos and story were on pages 4 and 5 (the centerfold).

With the departure of the 3rd Battalion, 21st Infantry, from the Da Nang area, August 11, 1972, U.S. forces officially ended participation in the ground war in Vietnam. At the peak of U.S. participation in the ground war three years ago, there was a total of 112 maneuver battalions engaged in the conflict.

Soldiers from the Battalion will either be reassigned to other units within the Republic of Vietnam or returned to the United States using usual returnee procedures.

Nicknamed "The" Gimlets," th" unit arrived in Vietnam August 14, 1966 Originally they operated in Tay Ninh Provence, Military Region III In April 1967 the Battalion along with its parent brigade was attached to Task Force Oregon and shifted to Chu Lai in Quang Tin and Quang Provence, Military Region I.

The task force was later organized into the U.S. 23rd Division (Americal) and participated in several large operations conducted in Quang Tin and Quang Ngai Provinces.

More recently, the Battalion was moved to Da Nang, providing security for the air base and other military units in the area. Lieutenant Colonel Rocco Negris of Springfield, VA, was the Battalion's commander. The South Vietnamese 3rd Infantry Division has assumed the duties of the Battalion.

FREEDOM BIRDS ARRIVE to pick up the last U.S. ground troops from the field, seven miles west of Da Nang. These four helicopters executed the entire extraction.

FREEDOM BIRDS ARRIVE to pick up the last U.S. ground troops from the field, seven miles west of Da Nang. These four helicopters executed the entire extraction.

NOTE: In addition to the CBS Team and me, the helos were also bringing in the RVN replacements Th They'dp off the RVN soldiers and pick up the U.S. soldiers Why only four Well, by that time there wereweren't that many U.S. Hueys available By the time I left country a month later, there were less than six U.S. Army Hueys in I Corps sporting a U.S flag on their tail.

ARIEL VIEW OF HILL 260, occupied by B Battery 3/22nd Field Artillery. As part of Task Force Gimlet, they supported the 3rd Battalion until they were withdrawn from the field. Da Nang AB is in the distance to the right (This photo was in the story, but reversed L to R)

ARIEL VIEW OF HILL 260, occupied by B Battery 3/22nd Field Artillery. As part of Task Force Gimlet, they supported the 3rd Battalion until they were withdrawn from the field. Da Nang AB is in the distance to the right (This photo was in the story, but reversed L to R)

When riding around in U.S. Hueys I used to sit in the doorway (as shown) – dumb, eh Later, when I flew ARVN, I sat in the middle holding on to the pilopilot'st brace (as ARVN removed seats, medical kits and other black marketable items).

When riding around in U.S. Hueys I used to sit in the doorway (as shown) – dumb, eh Later, when I flew ARVN, I sat in the middle holding on to the pilopilot'st brace (as ARVN removed seats, medical kits and other black marketable items).

BACKGROUND COMMENTS – Photo with captions sent to MACV but not used: I was escorting Ken Wagner and his CBS news team (below), not published in the MACV Observer.

Ken Wagner and CBS News Crew Awaiting Setup CBS news crew's photographer is left of the flag

NOTE: This particular round had a brass casing, yes, brass. It was acquired and saved specifically for this last shot. Prior to this last shot, the battery fired a salvo on a distant ridge. The smoke plumes rising on the horizon were in the form of "flying the bird." We're done!

Last Artillery Round to be Fired!

Last Artillery Round to be Fired!

EPILOG:

The CBS news crew and I stayed until the U.S. motorcade left the firebase and all others were extracted by Hueys. For us, there was a certain uneasiness. After what seemed an eternity, a lone helo returned that afternoon to retrieve us. In stepping onto the skid, I was (effectively) the last U.S. soldier to leave a U.S. firebase in RVN It was a long day.

TWS allowed me to reconnect with shipmates I had lost track of over the years. You title this forum "Reflections of your Service," and that is actually what this site allows you to do: reflect on your service and share that with the shipmate who stood watch with you, laughed with you, and even cried with you. What a ride it was!

ITC(SW) Richard P. Cooper, US Navy (Ret)

1983-2008

He was a helicopter pilot; I was a medical corpsman serving with the First Marine Division. Our paths never crossed while we both served our country in the Vietnam War, but oh how they would cross as we met in the emergency room one fateful Friday the 13th.

He was a helicopter pilot; I was a medical corpsman serving with the First Marine Division. Our paths never crossed while we both served our country in the Vietnam War, but oh how they would cross as we met in the emergency room one fateful Friday the 13th.

I'll call him Bob* for the purpose of this real-life story. Bob returned to civilian life and continued flying helicopters while I returned to college, eventually medical school, and ultimately became a board-certified family physician. I landed in a small rural community often laden with tourists who came to enjoy the beauty that our community offered. Bob ended up in the same community, flying these tourists in his sightseeing helicopter. I flew in many helicopters in Vietnam, but never did feel comfortable in them, especially when the Viet Cong were constantly shooting at them.

Our community hospital was small, 100 beds, and had a six-bed ICU. We had one general surgeon, one internist, and a handful of family physicians. At my urging, the hospital agreed to purchase a new Bennett MA-1 ventilator, mostly used for older patients with respiratory failure. Fortunately, I was fresh out of training from a major medical center where the first critical care medicine fellowship was started by an aggressive group of research anesthesiologists and pulmonologists using high PEEP and treating traumatic lung injuries. I was fortunate enough to spend several months in their unit and little did I know that that experience would help to save Bob's life.

I was in the emergency room when the ambulance arrived with two survivors of a helicopter crash. One was Bob, the pilot, and the other was a 7-year-old girl. Two others in the helicopter were unfortunately killed when the tail rotor on Bob's helicopter came off at an altitude of 700 feet, and they plummeted to the ground. This occurred on the worst of days, Friday the 13th.

I was in the emergency room when the ambulance arrived with two survivors of a helicopter crash. One was Bob, the pilot, and the other was a 7-year-old girl. Two others in the helicopter were unfortunately killed when the tail rotor on Bob's helicopter came off at an altitude of 700 feet, and they plummeted to the ground. This occurred on the worst of days, Friday the 13th.

It was apparent to me that Bob had a flail chest. I had seen that in Vietnam as a result of explosive shrapnel and had seen it once in my residency. Bob's flail chest was a result of him striking the center console on the helicopter. I immediately intubated Bob and put a chest tube in the right and left chest cavities, aiding his flail chest. Both he and the 7-year-old girl had deceleration injuries to their livers and spleens as evidenced by abdominal taps (pre CT scan era). By this time, we had all the doctors on our staff in the ER. Our general surgeon asked a thoracic surgeon to travel the 40 miles from a larger medical center to help him with the liver and spleen lacerations.

The 7-year-old girl recovered nicely and went home within a week, minus her spleen. Bob, who also lost his spleen, was unfortunately connected to the one and only ventilator. Both the general surgeon and thoracic surgeon agreed Bob should stay in our small hospital and not be moved, but this meant I would have to become a resident again and live at the hospital for the next 10 days managing his ventilator, managing his chest tubes until they could be removed, and caring for him until he could be extubated. He had also suffered a compression fracture of the spine and a fractured ankle as a result of the crash.

After he was extubated, I learned he was a veteran of the Vietnam War, and so, as veterans tend to do, we shared old war stories about where we served and what we experienced. Our relationship became more than just doctor and patient. We would talk about cars and the war, and I would always tell Bob that I never wanted to see another helicopter as long as I lived. Bob eventually recovered and moved away; he even went back to flying helicopters. Every year, for many years, I got a nice card and flowers from Bob on the anniversary of his crash.

Then several years ago, Bob and his wife showed up in my office. He and his wife had retired and decided to move back to our community. I was happy to see an old patient, and an old friend, whose life had impacted me so much. He now had arthritis, heart and lung disease, and walked with a cane, but his spirit was still upbeat. He was still the same old Bob, always laughing at me for my fear of helicopters. I was fortunate enough to know and care for Bob and his wife for many years after that.

Then several years ago, Bob and his wife showed up in my office. He and his wife had retired and decided to move back to our community. I was happy to see an old patient, and an old friend, whose life had impacted me so much. He now had arthritis, heart and lung disease, and walked with a cane, but his spirit was still upbeat. He was still the same old Bob, always laughing at me for my fear of helicopters. I was fortunate enough to know and care for Bob and his wife for many years after that.

I recently returned from Bob's funeral. He had made it to his 80th birthday. He was buried with full military honors. I saluted his flag-draped coffin and said goodbye to my patient, my friend, and an old war buddy that I will miss so much.

*All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Bob Parsons was a 0311, a Marine Corps Rifleman, with 1st Battalion 26th Marines in South Vietnam's Quang Nam province. When he first arrived on Hill 190, where his company operated, it was all rice paddy as far as his eyes could see. He was told that his time in-country would change him. He may not have realized just how much he would change.

Bob Parsons was a 0311, a Marine Corps Rifleman, with 1st Battalion 26th Marines in South Vietnam's Quang Nam province. When he first arrived on Hill 190, where his company operated, it was all rice paddy as far as his eyes could see. He was told that his time in-country would change him. He may not have realized just how much he would change.

If his name sounds familiar, that's because Bob Parsons was the founder of GoDaddy.com, a billionaire serial entrepreneur, and philanthropist. He has not only donated hundreds of millions to the Semper Fi & America's Fund, but has also signed on to the Giving Pledge, promising to give away at least half his fortune.

His new book, "Fire in the Hole! The Untold Story of My Traumatic Life and Explosive Success," is not just about his time in Vietnam; it's the story of what his life was like before and after the war.

"Despite and because of the gruesome things that I saw, Vietnam shaped me in so many ways, it changed me to the core," Parsons writes in his book. "What I went through, what I witnessed and how I survived is a big part of who I am today… I am certain that had I not gone through Vietnam, I wouldn't have accomplished all that I have over the years."

Parsons' unit was assigned to make squad-level ambushes against the North Vietnamese Army to keep them from harassing the villages in their operating area. Those rice paddies were a far cry from the life he led growing up poor in Baltimore. He was the son of a furniture salesman and a homemaker, and he was never a particularly good student. But when his high school teachers learned he signed up for the Marine Corps, they gave him passing grades so he could graduate.

When he actually arrived in Vietnam, however, things changed. He suddenly became aware of the danger he was in. His heart began to race as the task of staying alive seemed insurmountable. As darkness closed in over him, he realized he was going to die there. But that realization lifted his spirits. The darkness receded, and he felt relieved. He decided then and there he would only worry about being the best Marine he could be for his fellow Marines and that he would only ever look forward to the next day's mail call.

When he actually arrived in Vietnam, however, things changed. He suddenly became aware of the danger he was in. His heart began to race as the task of staying alive seemed insurmountable. As darkness closed in over him, he realized he was going to die there. But that realization lifted his spirits. The darkness receded, and he felt relieved. He decided then and there he would only worry about being the best Marine he could be for his fellow Marines and that he would only ever look forward to the next day's mail call.

Parsons was wounded while fighting in Vietnam, a memory he recalls very well in the book. When he came home, his life was entirely different than the one he left behind. He went to college and became a CPA, started a software company (that he would sell for millions), founded GoDaddy, started a family, and, after all that, finally dealt with the trauma from Vietnam that haunted him the whole time.

"Fire in the Hole!" is not only Bob Parsons' hilarious reflection on his military service, it's a book about leadership principles, the mindset of an entrepreneur, and a self-help book for anyone who struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder. All of these come together in one very readable, digestible, and engrossing narrative, told in the unabashed way we've come to expect from Bob Parsons.

"Fire in the Hole! The Untold Story of My Traumatic Life and Explosive Success" is available on Amazon in hardcover, Kindle ereader or audiobook starting at $13.28. Or you can get the book straight from Bob Parsons' company PXG for $14.50.

To call the Murph a "grueling" workout would be an understatement, but it was something he did regularly, and it helped him fight on in the mountains of Afghanistan against incredible odds. Without his valiant physical and mental efforts that day, his entire team might have vanished without a trace.

To call the Murph a "grueling" workout would be an understatement, but it was something he did regularly, and it helped him fight on in the mountains of Afghanistan against incredible odds. Without his valiant physical and mental efforts that day, his entire team might have vanished without a trace.  Some goat herders happened to stumble upon the SEALs' hideout spot. They were detained but when Murphy determined they weren't enemy combatants and actually were goat herders and thus not legitimate targets, he set them free in accordance with the laws of armed conflict. Knowing full well the herdsmen would report the SEALs to their local militia leaders, likely Shah himself, the Americans decided to retreat. They didn't make it far enough, fast enough, because it wasn't long before Afghan militia fighters were on them with small arms, machine guns, mortars, and RPGs. The heavy, intense enemy fire forced the SEALs into a gulch on the far side of the mountain, making communication nearly impossible.

Some goat herders happened to stumble upon the SEALs' hideout spot. They were detained but when Murphy determined they weren't enemy combatants and actually were goat herders and thus not legitimate targets, he set them free in accordance with the laws of armed conflict. Knowing full well the herdsmen would report the SEALs to their local militia leaders, likely Shah himself, the Americans decided to retreat. They didn't make it far enough, fast enough, because it wasn't long before Afghan militia fighters were on them with small arms, machine guns, mortars, and RPGs. The heavy, intense enemy fire forced the SEALs into a gulch on the far side of the mountain, making communication nearly impossible.

Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison was notorious long before U.S. troops were found guilty of abusing detainees there. Originally built in the 1960s, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein used the site to house and later execute political prisoners. He closed the prison in 2002, but when the U.S.-led Coalition ousted Hussein by force in 2003, it was reopened. Because Coalition forces used it as an internment camp, it also became a forward operating base – and a target for insurgents.

Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison was notorious long before U.S. troops were found guilty of abusing detainees there. Originally built in the 1960s, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein used the site to house and later execute political prisoners. He closed the prison in 2002, but when the U.S.-led Coalition ousted Hussein by force in 2003, it was reopened. Because Coalition forces used it as an internment camp, it also became a forward operating base – and a target for insurgents.  The plan was surprisingly sophisticated. At about an hour after sunset on April 2, 2005, a large number of insurgent fighters fired small arms, rocket-propelled grenades, and mortars at strategic points inside the Abu Ghraib complex. While the American defenders inside scrambled to see where the attacks were coming from and mount a defense, a Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Device – or VBIED, Iraq War parlance for a large car bomb – drove toward the walls of the base, to blow a hole in the compound, creating a breach for insurgents to exploit.

The plan was surprisingly sophisticated. At about an hour after sunset on April 2, 2005, a large number of insurgent fighters fired small arms, rocket-propelled grenades, and mortars at strategic points inside the Abu Ghraib complex. While the American defenders inside scrambled to see where the attacks were coming from and mount a defense, a Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Device – or VBIED, Iraq War parlance for a large car bomb – drove toward the walls of the base, to blow a hole in the compound, creating a breach for insurgents to exploit.

After nearly two and a half hours of intense fighting, the defenses at Abu Ghraib held. NBC News reported that insurgents used nine different car bombs or IEDs during the attack, along with more than a hundred mortar rounds and 10,000 rounds of small arms ammunition. American estimates of insurgent casualties numbered more than 70. The Americans had 44 wounded and no one killed in action.

After nearly two and a half hours of intense fighting, the defenses at Abu Ghraib held. NBC News reported that insurgents used nine different car bombs or IEDs during the attack, along with more than a hundred mortar rounds and 10,000 rounds of small arms ammunition. American estimates of insurgent casualties numbered more than 70. The Americans had 44 wounded and no one killed in action.

There are a lot of military myths and urban legends out there, but few are more widespread or ridiculous than the legend of the base flagpole truck. No one knows who started it or why. It's just a legend that has been passed down from generation to generation of veterans. It transcends military branches and eras of wars, and it is as common to hear the myths of saltpeter in the Gatorade or "etherbunny."

There are a lot of military myths and urban legends out there, but few are more widespread or ridiculous than the legend of the base flagpole truck. No one knows who started it or why. It's just a legend that has been passed down from generation to generation of veterans. It transcends military branches and eras of wars, and it is as common to hear the myths of saltpeter in the Gatorade or "etherbunny."  There are many problems with this specific myth. First, the idea that a permanent American military installation is being overrun is absurd. American troops will call in airstrikes on their own position rather than just let the enemy overrun their fellow soldiers. Secondly, as much as troops love Old Glory, if their base is being overrun, the base flagpole is not a high priority. Finally, imagine how long it would take to bring down the flag and burn it respectfully. Retreating soldiers have better things to do.

There are many problems with this specific myth. First, the idea that a permanent American military installation is being overrun is absurd. American troops will call in airstrikes on their own position rather than just let the enemy overrun their fellow soldiers. Secondly, as much as troops love Old Glory, if their base is being overrun, the base flagpole is not a high priority. Finally, imagine how long it would take to bring down the flag and burn it respectfully. Retreating soldiers have better things to do.

The peninsular state of Michigan (est. 1837) resembles an extended left human hand in a mitt with the thumb partly opened outward from the palm. And there, about where the quick of a thumbnail would be on the east side, is US Coast Guard Station Harbor Beach as it's known today. It is estimated that since the 17th century, there are 6,000 maritime wrecks at the bottom of the mighty Great Lakes, one of which is Lake Huron. District 9, consisting of forty-eight active stations, is a United States Coast Guard area of operations based in Cleveland, Ohio. It is responsible for all Coast Guard functions on the five Great Lakes, the Saint Lawrence Seaway, and surrounding states, accumulating 6,700 miles of shoreline and 1,500 miles of international shoreline with Canada. It includes roughly 6,000 active duty, reserve, and civilian personnel serving duties such as search and rescue, maritime safety and security, environmental protection, maritime law enforcement, aids to navigation, and icebreaking. About sixty miles north of Port Huron, Station Harbor Beach (area pop. 1,604 in 2020) is one of eight USCG facilities in Sector Detroit. Originally named Barnettsville in 1855, the town was settled as a sawmill and shipping port, sending lumber down into and out of the Saginaw riverine system; eventually becoming known as Sand Beach by 1899, which changed again to Harbor Beach (est. 1910). It offers the largest man-made freshwater harbor of refuge to ships traveling between Port Huron and Pointe Aux Barques, against record temperatures between -22 and +95, with snowfall totaling as much as fifty inches, six months of the year.

The peninsular state of Michigan (est. 1837) resembles an extended left human hand in a mitt with the thumb partly opened outward from the palm. And there, about where the quick of a thumbnail would be on the east side, is US Coast Guard Station Harbor Beach as it's known today. It is estimated that since the 17th century, there are 6,000 maritime wrecks at the bottom of the mighty Great Lakes, one of which is Lake Huron. District 9, consisting of forty-eight active stations, is a United States Coast Guard area of operations based in Cleveland, Ohio. It is responsible for all Coast Guard functions on the five Great Lakes, the Saint Lawrence Seaway, and surrounding states, accumulating 6,700 miles of shoreline and 1,500 miles of international shoreline with Canada. It includes roughly 6,000 active duty, reserve, and civilian personnel serving duties such as search and rescue, maritime safety and security, environmental protection, maritime law enforcement, aids to navigation, and icebreaking. About sixty miles north of Port Huron, Station Harbor Beach (area pop. 1,604 in 2020) is one of eight USCG facilities in Sector Detroit. Originally named Barnettsville in 1855, the town was settled as a sawmill and shipping port, sending lumber down into and out of the Saginaw riverine system; eventually becoming known as Sand Beach by 1899, which changed again to Harbor Beach (est. 1910). It offers the largest man-made freshwater harbor of refuge to ships traveling between Port Huron and Pointe Aux Barques, against record temperatures between -22 and +95, with snowfall totaling as much as fifty inches, six months of the year.  of their harbor, changed its name to Harbor Beach, and the cast-iron lighthouse has subsequently been known as Harbor Beach Lighthouse. In 1934, a cable was run from shore to provide commercial power to the lighthouse and fog signal, and a radio beacon was established at the station. The last Coast Guard crew left the lighthouse after the 1967 shipping season, which actually ran until 2 January 1968, and no longer after that, the fog signal building was removed. The tower's Fresnel lens was removed in 1986 and placed on display at the Grice House Museum in Harbor Beach. In 2004, Harbor Beach Lighthouse, deemed excess by the Coast Guard, was offered at no cost to eligible entities under the provisions of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000. Founded in 1898 as the US Coast Guard took over a Lifeboat Station for the US Lifesaving Service, Station Harbor Beach in the 1930s and saw heavy use during the Second World War, training new Coast Guard recruits. The station was closed as a full-time facility in 1973 due to budget restrictions, but it remained operational as a seasonal, summer-only station manned by USCG Auxiliary and Reserve Units. In 2004, Station Harbor Beach was formally re-opened as a full-time, fully crewed station and remains so today as part of the US Coast Guard's 9th District, Sector Detroit.

of their harbor, changed its name to Harbor Beach, and the cast-iron lighthouse has subsequently been known as Harbor Beach Lighthouse. In 1934, a cable was run from shore to provide commercial power to the lighthouse and fog signal, and a radio beacon was established at the station. The last Coast Guard crew left the lighthouse after the 1967 shipping season, which actually ran until 2 January 1968, and no longer after that, the fog signal building was removed. The tower's Fresnel lens was removed in 1986 and placed on display at the Grice House Museum in Harbor Beach. In 2004, Harbor Beach Lighthouse, deemed excess by the Coast Guard, was offered at no cost to eligible entities under the provisions of the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000. Founded in 1898 as the US Coast Guard took over a Lifeboat Station for the US Lifesaving Service, Station Harbor Beach in the 1930s and saw heavy use during the Second World War, training new Coast Guard recruits. The station was closed as a full-time facility in 1973 due to budget restrictions, but it remained operational as a seasonal, summer-only station manned by USCG Auxiliary and Reserve Units. In 2004, Station Harbor Beach was formally re-opened as a full-time, fully crewed station and remains so today as part of the US Coast Guard's 9th District, Sector Detroit. was huddled together at the stern, desperately awaiting their rescuers… As the lifeboat headed between the piers, a wave broached the vessel, spinning it violently and throwing its occupants into the lake. Once in the water, they were pulled back and forth from the beach by a backwash created by waves crashing into the shore… The Lifesaving Service district superintendent would write, 'Braver men never manned an oar.' They were met with a hero's welcome when they returned to Harbor Beach, and two of them would go on to become keepers of their own stations. 'They were made of stern stuff,' [marine artist] Robert McGreevy said at the time. The five St. Clair crew members were initially buried together in the Port Sanilac Cemetery in what was described as a pauper's grave. Jones and one of his crew were eventually relocated to their hometown of Bay City. Graveratte, 30-year-old seaman George McFarland of Cleveland and 30-year-old Henry Anderson of Australia remain interred in the cemetery. A large gravestone was later placed at their burial site, adorned with an anchor and bearing an inscription recounting the events of Oct. 1-2, 1888." In 1915, the life-saving service was combined with the United States Revenue Service and became the United States Coast Guard. A Coast Guard Station was built in 1935 at the foot of Pack Street. An earthen causeway was laid out into the lake for a four-bay garage.

was huddled together at the stern, desperately awaiting their rescuers… As the lifeboat headed between the piers, a wave broached the vessel, spinning it violently and throwing its occupants into the lake. Once in the water, they were pulled back and forth from the beach by a backwash created by waves crashing into the shore… The Lifesaving Service district superintendent would write, 'Braver men never manned an oar.' They were met with a hero's welcome when they returned to Harbor Beach, and two of them would go on to become keepers of their own stations. 'They were made of stern stuff,' [marine artist] Robert McGreevy said at the time. The five St. Clair crew members were initially buried together in the Port Sanilac Cemetery in what was described as a pauper's grave. Jones and one of his crew were eventually relocated to their hometown of Bay City. Graveratte, 30-year-old seaman George McFarland of Cleveland and 30-year-old Henry Anderson of Australia remain interred in the cemetery. A large gravestone was later placed at their burial site, adorned with an anchor and bearing an inscription recounting the events of Oct. 1-2, 1888." In 1915, the life-saving service was combined with the United States Revenue Service and became the United States Coast Guard. A Coast Guard Station was built in 1935 at the foot of Pack Street. An earthen causeway was laid out into the lake for a four-bay garage.  Pictured here, the current USCG facility. This is a "sparkplug lighthouse" located at the end of the north breakwall entrance to this harbor of refuge on Lake Huron. Coast Guard TWS lists twelve members who served at this station under its current name, and three who served there when it was called Sand Beach Station; so named owing, as with other variably windward coastal areas of Michigan, to unusually plentiful pure sand deposits and meteorological lake-effect.

Pictured here, the current USCG facility. This is a "sparkplug lighthouse" located at the end of the north breakwall entrance to this harbor of refuge on Lake Huron. Coast Guard TWS lists twelve members who served at this station under its current name, and three who served there when it was called Sand Beach Station; so named owing, as with other variably windward coastal areas of Michigan, to unusually plentiful pure sand deposits and meteorological lake-effect.

When hardline anti-communist Nixon took office in 1969, the United States was mired in the Vietnam War, and the new President had campaigned on ending American involvement there. When it came to Foreign Policy, Nixon and his tag team partner Kissinger were experts on another level. To cower the Soviet Union, China and North Vietnam, Nixon came up with a policy that would make communist leaders and their allies believe he was so irrational that he might start a nuclear war at any time.

When hardline anti-communist Nixon took office in 1969, the United States was mired in the Vietnam War, and the new President had campaigned on ending American involvement there. When it came to Foreign Policy, Nixon and his tag team partner Kissinger were experts on another level. To cower the Soviet Union, China and North Vietnam, Nixon came up with a policy that would make communist leaders and their allies believe he was so irrational that he might start a nuclear war at any time.  At this time, North Korea was at the height of its power but was still protected by the Soviet Union and its missile systems. It was militarily, economically, and industrially stronger than South Korea, but not the U.S. But the U.S. had communist problems elsewhere, too. In Vietnam, the United States was still recovering from the Tet Offensive the previous year. The Soviet Union and communist China were constant thorns in the side of American power. After a few drinks, President Nixon got sick of all of it and put the U.S. military on alert to carry out the SIOP or Single Integrated Operational Plan: the U.S. nuclear strike plan for war with the communists.

At this time, North Korea was at the height of its power but was still protected by the Soviet Union and its missile systems. It was militarily, economically, and industrially stronger than South Korea, but not the U.S. But the U.S. had communist problems elsewhere, too. In Vietnam, the United States was still recovering from the Tet Offensive the previous year. The Soviet Union and communist China were constant thorns in the side of American power. After a few drinks, President Nixon got sick of all of it and put the U.S. military on alert to carry out the SIOP or Single Integrated Operational Plan: the U.S. nuclear strike plan for war with the communists.

Contrary to popular opinion, the U.S. Army's departure from RVN was orderly, as were other U.S. units before them.

Contrary to popular opinion, the U.S. Army's departure from RVN was orderly, as were other U.S. units before them.

THE COLORS are lowered at the final retreat ceremony on Hill 260 overlooking Da Nang This was the last flag to fly over a U.S. support base in the Republic of Vietnam The ceremony was one of the activities marking the stand down of the 21st Infantry, and attached units – the last of the U.S. forces maneuver battalions in RVN.

THE COLORS are lowered at the final retreat ceremony on Hill 260 overlooking Da Nang This was the last flag to fly over a U.S. support base in the Republic of Vietnam The ceremony was one of the activities marking the stand down of the 21st Infantry, and attached units – the last of the U.S. forces maneuver battalions in RVN.  FREEDOM BIRDS ARRIVE to pick up the last U.S. ground troops from the field, seven miles west of Da Nang. These four helicopters executed the entire extraction.

FREEDOM BIRDS ARRIVE to pick up the last U.S. ground troops from the field, seven miles west of Da Nang. These four helicopters executed the entire extraction. ARIEL VIEW OF HILL 260, occupied by B Battery 3/22nd Field Artillery. As part of Task Force Gimlet, they supported the 3rd Battalion until they were withdrawn from the field. Da Nang AB is in the distance to the right (This photo was in the story, but reversed L to R)

ARIEL VIEW OF HILL 260, occupied by B Battery 3/22nd Field Artillery. As part of Task Force Gimlet, they supported the 3rd Battalion until they were withdrawn from the field. Da Nang AB is in the distance to the right (This photo was in the story, but reversed L to R)  When riding around in U.S. Hueys I used to sit in the doorway (as shown) – dumb, eh Later, when I flew ARVN, I sat in the middle holding on to the pilopilot'st brace (as ARVN removed seats, medical kits and other black marketable items).

When riding around in U.S. Hueys I used to sit in the doorway (as shown) – dumb, eh Later, when I flew ARVN, I sat in the middle holding on to the pilopilot'st brace (as ARVN removed seats, medical kits and other black marketable items).

Last Artillery Round to be Fired!

Last Artillery Round to be Fired!

He was a helicopter pilot; I was a medical corpsman serving with the First Marine Division. Our paths never crossed while we both served our country in the Vietnam War, but oh how they would cross as we met in the emergency room one fateful Friday the 13th.

He was a helicopter pilot; I was a medical corpsman serving with the First Marine Division. Our paths never crossed while we both served our country in the Vietnam War, but oh how they would cross as we met in the emergency room one fateful Friday the 13th.  I was in the emergency room when the ambulance arrived with two survivors of a helicopter crash. One was Bob, the pilot, and the other was a 7-year-old girl. Two others in the helicopter were unfortunately killed when the tail rotor on Bob's helicopter came off at an altitude of 700 feet, and they plummeted to the ground. This occurred on the worst of days, Friday the 13th.

I was in the emergency room when the ambulance arrived with two survivors of a helicopter crash. One was Bob, the pilot, and the other was a 7-year-old girl. Two others in the helicopter were unfortunately killed when the tail rotor on Bob's helicopter came off at an altitude of 700 feet, and they plummeted to the ground. This occurred on the worst of days, Friday the 13th. Then several years ago, Bob and his wife showed up in my office. He and his wife had retired and decided to move back to our community. I was happy to see an old patient, and an old friend, whose life had impacted me so much. He now had arthritis, heart and lung disease, and walked with a cane, but his spirit was still upbeat. He was still the same old Bob, always laughing at me for my fear of helicopters. I was fortunate enough to know and care for Bob and his wife for many years after that.

Then several years ago, Bob and his wife showed up in my office. He and his wife had retired and decided to move back to our community. I was happy to see an old patient, and an old friend, whose life had impacted me so much. He now had arthritis, heart and lung disease, and walked with a cane, but his spirit was still upbeat. He was still the same old Bob, always laughing at me for my fear of helicopters. I was fortunate enough to know and care for Bob and his wife for many years after that.

Bob Parsons was a 0311, a Marine Corps Rifleman, with 1st Battalion 26th Marines in South Vietnam's Quang Nam province. When he first arrived on Hill 190, where his company operated, it was all rice paddy as far as his eyes could see. He was told that his time in-country would change him. He may not have realized just how much he would change.

Bob Parsons was a 0311, a Marine Corps Rifleman, with 1st Battalion 26th Marines in South Vietnam's Quang Nam province. When he first arrived on Hill 190, where his company operated, it was all rice paddy as far as his eyes could see. He was told that his time in-country would change him. He may not have realized just how much he would change.  When he actually arrived in Vietnam, however, things changed. He suddenly became aware of the danger he was in. His heart began to race as the task of staying alive seemed insurmountable. As darkness closed in over him, he realized he was going to die there. But that realization lifted his spirits. The darkness receded, and he felt relieved. He decided then and there he would only worry about being the best Marine he could be for his fellow Marines and that he would only ever look forward to the next day's mail call.

When he actually arrived in Vietnam, however, things changed. He suddenly became aware of the danger he was in. His heart began to race as the task of staying alive seemed insurmountable. As darkness closed in over him, he realized he was going to die there. But that realization lifted his spirits. The darkness receded, and he felt relieved. He decided then and there he would only worry about being the best Marine he could be for his fellow Marines and that he would only ever look forward to the next day's mail call.