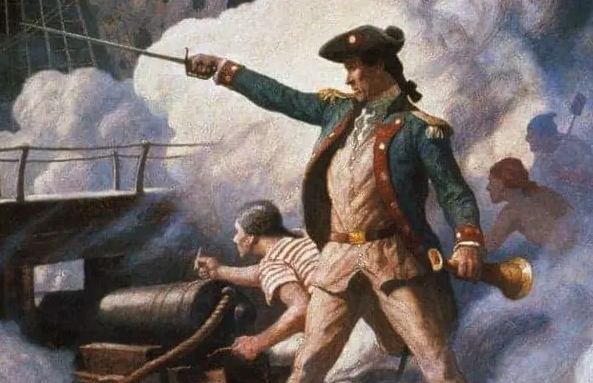

There is no shortage of heroes who rose to prominence during the American Revolution, but few compare to the legacy of John Paul Jones. A Scotsman by birth, he came to the fledgling United States but joined the Continental Navy as an American. Although many of his newfound countrymen would enjoy victories over Great Britain in the years to come, only Capt. John Paul Jones, the "Father of the U.S. Navy," would ever bring the war home to the British.

Born in 1747, young John Paul (not yet Jones) began his sailing career at the tender age of 13. He spent a considerable amount of time traveling across the Atlantic Ocean from England to Virginia as a merchant mariner. It was as a merchant that he got his first chance to command a ship. He was 21 years old when the captain and first mate of his ship suddenly died of Yellow Fever, and it was John Paul who successfully navigated the vessel back to its home waters.

Born in 1747, young John Paul (not yet Jones) began his sailing career at the tender age of 13. He spent a considerable amount of time traveling across the Atlantic Ocean from England to Virginia as a merchant mariner. It was as a merchant that he got his first chance to command a ship. He was 21 years old when the captain and first mate of his ship suddenly died of Yellow Fever, and it was John Paul who successfully navigated the vessel back to its home waters.

He soon became the ship's master, but after two voyages to the West Indies, he was forced to flog a mutinous crewman. When the crewman later died of wounds related to the flogging, he fled to London, where he commanded an armed merchantman. After he was accused of killing yet another crewman over wages in 1773, he fled once more. He reappeared in Virginia with the name John Paul Jones.

Jones fell in love with what would soon become the United States. So when it came time to break ties with Great Britain, he rushed to offer his seagoing services to the nascent Continental Navy. It would be his first step toward immortality. On Dec. 3, 1775, then-1st Lt. John Paul Jones raised the flag aboard the Alfred, his first ship in the Navy. A year later, he would take his first command in the Navy, a sloop named Providence.

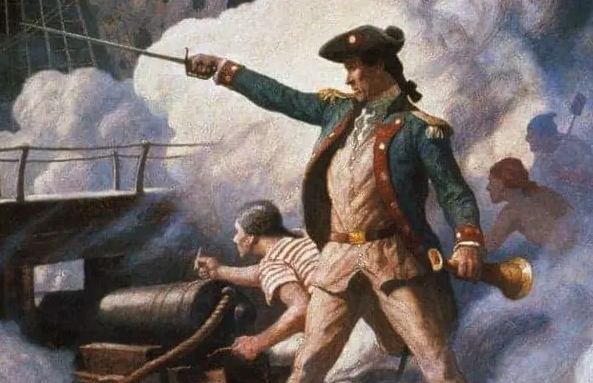

In command of the Providence, he captured eight enemy ships in the Atlantic, sunk or burned eight more, and took home several prizes. On June 14, 1777, he officially took command of a brand-new vessel, the Ranger. It was aboard this new ship that Jones would strike fear into the British public and would enter the history books of naval warfare. He was sent to the Irish Sea to wreak havoc on British shipping and ships at home. For two years, he was very successful at it.

In 1778, Jones and the Ranger captured the British warship HMS Drake in its home waters, then sold it to France, creating a furor among British citizens. Suddenly, the imposing Royal Navy wasn't as invincible as it once seemed. But it was shortly after taking Drake that he performed a feat no other American leader could do during the Revolutionary War: he attacked England itself.

In 1778, Jones and the Ranger captured the British warship HMS Drake in its home waters, then sold it to France, creating a furor among British citizens. Suddenly, the imposing Royal Navy wasn't as invincible as it once seemed. But it was shortly after taking Drake that he performed a feat no other American leader could do during the Revolutionary War: he attacked England itself.

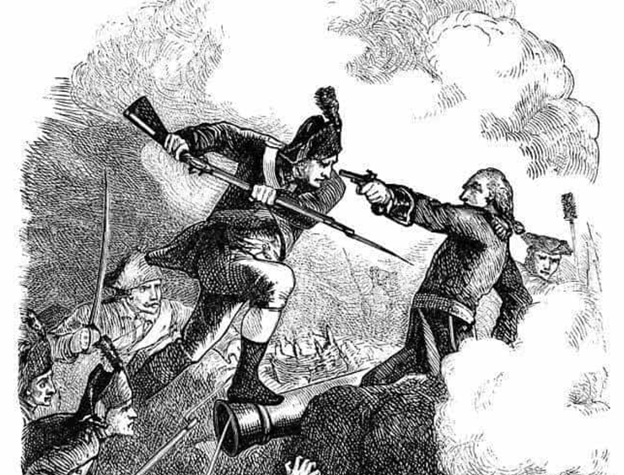

On Apr. 23, 1778, Jones and two boats filled with 30 men rowed into the waters of Whitehaven, England. Some 400 British ships were moored in the shallow harbor. They had intended to arrive at midnight, but trouble with the boats kept them until morning. Still, when dawn came, Jones and his men captured the harbor's southern fort, then set a fire that would burn the entire town.

To celebrate his victories, the French gave him a heavily armed frigate called the Duc de Duras. It was a slower warship than Jones would have liked, but it came with 42 guns, and that was enough for him. He rechristened it the Bonhomme Richard, named after Benjamin Franklin, and set out once again.

This time, at the head of a squadron of seven ships, Jones sailed around Ireland and Scotland. While there, he learned of a merchant convoy headed for London from the Baltic Sea. Since it was carrying war supplies that the British could no longer acquire from their American colonies, he knew he had to intercept them. Jones and his Franco-American squadron famously met HMS Serapis and the Countess of Scarborough at Flamborough Head, off the coast of Yorkshire.

This time, at the head of a squadron of seven ships, Jones sailed around Ireland and Scotland. While there, he learned of a merchant convoy headed for London from the Baltic Sea. Since it was carrying war supplies that the British could no longer acquire from their American colonies, he knew he had to intercept them. Jones and his Franco-American squadron famously met HMS Serapis and the Countess of Scarborough at Flamborough Head, off the coast of Yorkshire.

After three and a half hours of fighting, the Bonhomme Richard rammed the Serapis, lashed onto her with boarders, and forced its surrender with a tactical grenade. The Bonhomme Richard would be lost and the rest of the merchant fleet would sail on, but Jones, in command of the Serapis, sailed for the Netherlands, where he was welcomed as a hero.

The Battle of Green Spring isn't as celebrated a battle as the great American victories at Saratoga or Cowpens, but it is a relatively simple meeting between two great opposing forces, one that would demonstrate the evolution of the Continental Army in the face of superior British numbers and firepower.

The Battle of Green Spring isn't as celebrated a battle as the great American victories at Saratoga or Cowpens, but it is a relatively simple meeting between two great opposing forces, one that would demonstrate the evolution of the Continental Army in the face of superior British numbers and firepower.

It was the summer of 1781, and the outnumbered Marquis de Lafayette was dogging British Gen. Charles Cornwallis as the two armies tried to outmaneuver one another across Virginia. With 7,000 experienced troops, Lord Cornwallis was eager to trap Lafayette's 3,000-strong force, which was filled with mostly inexperienced militiamen.

Lafayette deftly dodged the British attempts to force an engagement, but his harassment of the British forces grew bolder when he received reinforcements, around 1,000 Continental Army troops under the legendary Gen. "Mad" Anthony Wayne.

When Cornwallis' movement suddenly shifted eastward, Lafayette correctly deduced the British were headed to the coast and that they would have to cross the James River. Lafayette believed that Cornwallis was in retreat and that his forces were overextended. In truth, despite having retreated several times, Cornwallis allowed the Americans to think he was forced to do so and even set up an elaborate ruse to lure them in. After the June 26th Battle at Spencer's Ordinary, he pretended to withdraw toward Portsmouth in the southeast, where he might be resupplied.

the James River. Lafayette believed that Cornwallis was in retreat and that his forces were overextended. In truth, despite having retreated several times, Cornwallis allowed the Americans to think he was forced to do so and even set up an elaborate ruse to lure them in. After the June 26th Battle at Spencer's Ordinary, he pretended to withdraw toward Portsmouth in the southeast, where he might be resupplied.

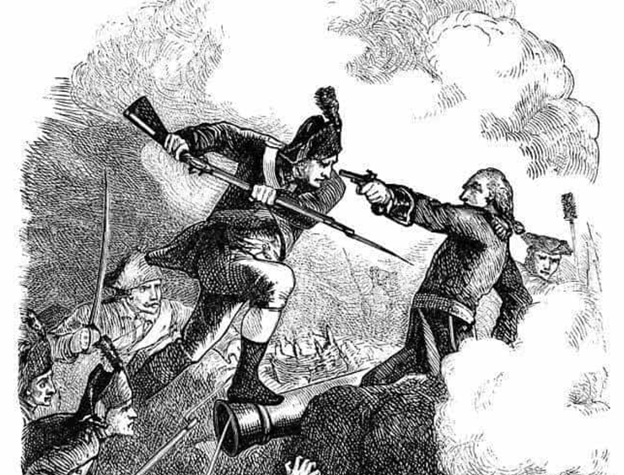

This is why the aggressive Lafayette planned to hit Cornwallis and his forces as they tried to cross the wide James River. When the Americans arrived at the British position near Green Spring Plantation on July 6, they found what they believed was Cornwallis' rearguard, a small force under Banastre Tarleton. Wayne's troops began to skirmish with Tarleton as Lafayette rode to get a better view of the battlefield.

When he did, he saw the large lines of Redcoats hidden out of sight of Wayne and the rest of the Continentals. He realized they were about to ride into a trap. Cornwallis had finally fooled Lafayette into investing in a battle, and he was about to face the entire British force. He rode to warn Gen. Wayne, but it was too late. Wayne's flanks exploded with canister and grapeshot, followed by an infantry charge.

Lafayette was undeterred, however, and ordered reinforcements to prevent Wayne from being surrounded or captured. Wayne, realizing his situation was precarious, believed that ordering a general retreat would chaotically dissolve his army, so he did what no one else but "Mad" Anthony Wayne would do. He ordered his 500 men to fix bayonets and then charged the 7,000-strong British Army.

Lafayette was undeterred, however, and ordered reinforcements to prevent Wayne from being surrounded or captured. Wayne, realizing his situation was precarious, believed that ordering a general retreat would chaotically dissolve his army, so he did what no one else but "Mad" Anthony Wayne would do. He ordered his 500 men to fix bayonets and then charged the 7,000-strong British Army.

It sounds crazy, and that's how Gen. Wayne earned his nickname, but the audacious plan actually worked. They pushed the British back for long enough that Lafayette's men were able to arrive and facilitate an orderly retreat. It was a tactical and strategic victory for the British, but the American force was able to survive and fight another day.

Cornwallis decided not to pursue them and instead crossed the river. As Lafayette and Wayne licked their wounds in Richmond, Cornwallis received orders to establish a supply base on the Virginia coast. He chose to dig in at a place called Yorktown.

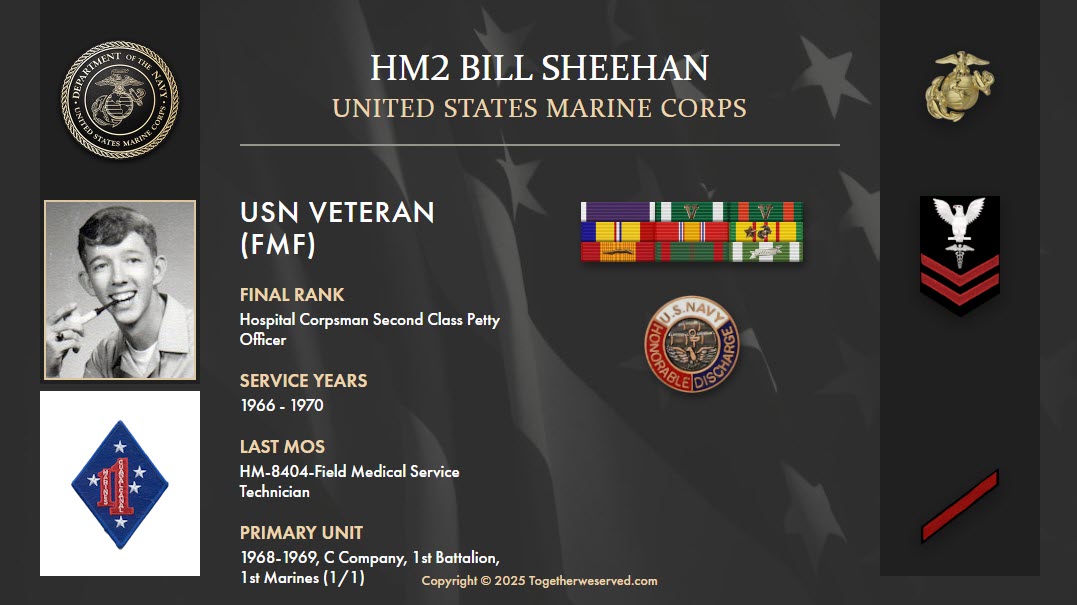

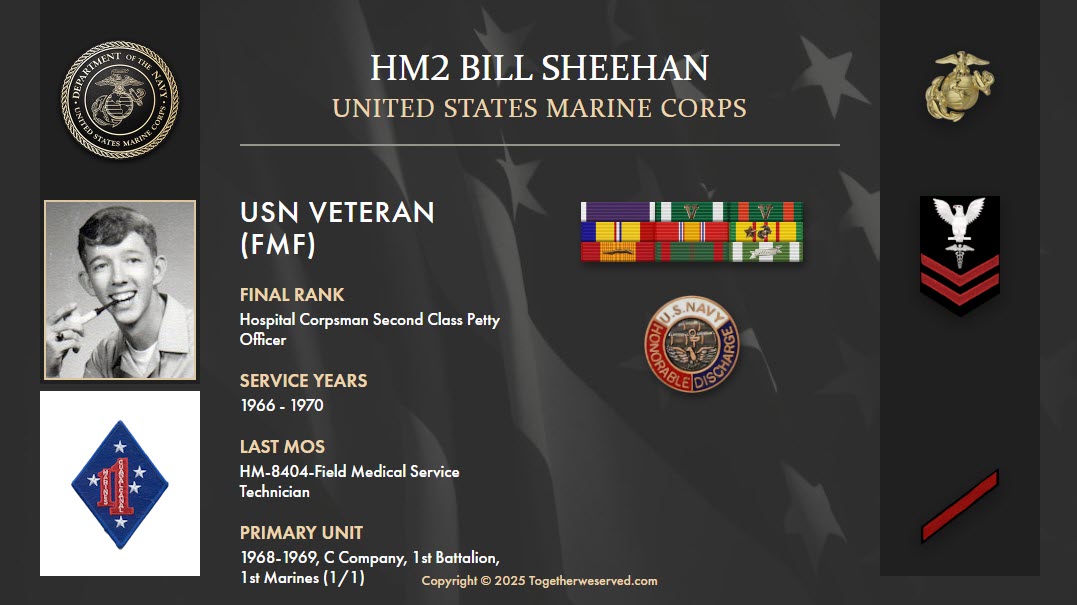

Thanks to this website, I have been fortunate to reunite with several comrades from my time in the service. I believe we are all more the same than you can imagine, and through this website, you will find that out. It has served me well, and I will continue to support it in the future.

I am truly honored to be able to have a profile on the Navy and the Marine Corps websites.

I thank Together We Served for allowing me to use their website name for the title of my book,

"Together We Served."

In October 2024, "Together We Served" was named the Winner of the Military Category in the 2024 International Impact Book Awards..

HM2 Bill Sheehan, US Navy Veteran

Served 1966-1970

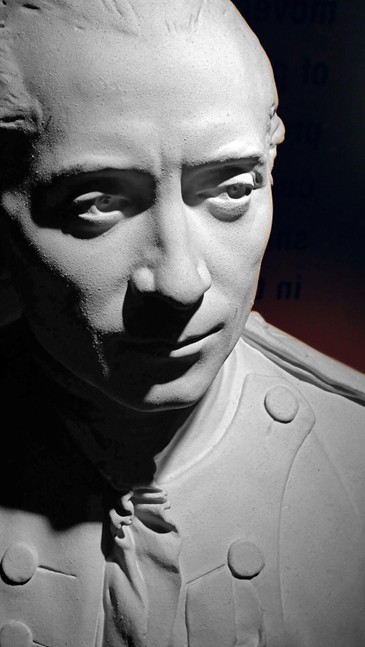

The average American living in Ohio and Pennsylvania may not know exactly who Gen. Anthony Wayne was, what he did, or what became of the man, but they've definitely heard his name, because so many streets and buildings are named after him there.

But those who drive along U.S. Route 322 through Pennsylvania might even catch a glimpse of him, even though he's been dead for almost 230 years.

But those who drive along U.S. Route 322 through Pennsylvania might even catch a glimpse of him, even though he's been dead for almost 230 years.

Wayne was a politician, a Founding Father, and a soldier whose exploits and daring in combat earned him the nickname "Mad" Anthony Wayne. As a Revolutionary War commander, he was fearless, ordering his troops to remove their musket flints at the Battle of Stony Point to ensure they would not only be silent but also engage the British in hand-to-hand combat at night. The gamble worked. After 30 minutes, the British were routed and the Americans captured the cliffs. It was also the second time he'd used that tactic.

But his battlefield legend doesn't end there. During the 1778 Battle of Monmouth, his force was abandoned by Gen. Charles Lee and was pinned down and outnumbered by the British. Through sheer tyranny of will and a lot of swearing, Wayne rallied his men to hold off repeated enemy bayonet charges and hold the field until George Washington could arrive with a relief force.

That's pretty much how Wayne's Revolutionary War battles went, because he didn't believe in maintaining a line of battle; he believed in outmaneuvering the enemy. He went on to become a U.S. Representative and the commander of the Legion of the United States, which is probably the most badass title the Army ever bestowed on anyone until World War II. "Mad" Anthony Wayne died in 1796, some say by poison and betrayal, but most believe it was complications from gout.

That's pretty much how Wayne's Revolutionary War battles went, because he didn't believe in maintaining a line of battle; he believed in outmaneuvering the enemy. He went on to become a U.S. Representative and the commander of the Legion of the United States, which is probably the most badass title the Army ever bestowed on anyone until World War II. "Mad" Anthony Wayne died in 1796, some say by poison and betrayal, but most believe it was complications from gout.

But this is where his afterlife somehow gets even more interesting than his actual life.

To put it simply: "Mad" Anthony Wayne is buried in two places. He was first interred at Fort Presque Isle in Pennsylvania, but his family wanted his remains moved to the family plot in Radnor, close to Philadelphia. When they dug him up 13 years later, Wayne's remains still looked remarkably fresh, as if he hadn't been dead long at all. It was going to be difficult to move.

So to make moving his body easier, Wayne's family had the body dismembered and boiled so the meat fell off the bones. Wayne's son was given the bones to move to Radnor, while the rest of the Founding Father was reinterred in Erie. Apparently, however, some of his bones fell out of the cart along the way. Legend has it that the ghost of "Mad" Anthony Wayne can be seen along Route 332 every January 1st, as the general searches for his skeletal remains.

"He's a man given a name for his victories in space

He's honored by history… We call him 'Ace' "

By: Frank Kibbe, 56th Fighter Group

In the skies over Europe from 1943 to 1945, the 56th established itself as the USAAF's top fighter group and created a legacy that will never be surpassed.

This storied unit, "Zemke's Wolfpack," by itself is represented on Air Force TWS with sixty-four registered members. However, its history with, currently, sixty-eight other numerically associated air and ground units (e.g. Wing, Supply, Medical, etc.) includes hundreds more airmen under and bearing the original insignia right up to the present time with 56th OG. A summary of its full parent lineage, not including subordinate squadrons, would include: AAC 56th Pursuit group 1940-41, then the AAF 56th FG itself until 1946, redesignated 56th Fighter Interceptor Group 1950-52, 56th Fighter Group (Air Defense) 1955-1961, 56th Tactical Fighter Group 1985-1991, and 56th Operations Group 1991- present. Chronologically, the Group has been stationed at Savannah AB, Charlotte AAB, Teaneck Armory, RAF Kingscliffe, RAF Horsham St Faith, RAF Halesworth, RAF Boxted, RAF Little Walden, Camp Kilmer, Selfridge Field, O'Hare Intl Airport, K.I. Sawyer AFB, MacDill AFB, and Luke AFB. At various times it was assigned to the Southeast Air District, III Interceptor Command, I Interceptor Command, New York Defense Wing, VIII Fighter Command, 4th Air Defense Wing, 66th Fighter Wing, 8th Air Force, 15th Air Force, 4706th Air Defense Wing, 37th Air Division, Sault Sainte Marie Air Defense Sector, and 56th Fighter Wing with attachments to 17th Bombardment Wing (L), III Interceptor Command, 65th Combat Fighter Wing (VLR) and 30th Air Division. Over its long service 56th FG pilots alone have flown the P-35, P-36, P-39, P-40, P-47, P-51, F-80, F-86, F-94, F-101, F-15 and F-16 aircraft. Their air and ground personnel have earned unit honors including: World War II and American Theater Service Streamers; World War II Air Offensive, Europe Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace, and Central Europe Air Combat Campaign Streamers; an EAME Theater Armed Forces Expeditionary Streamer; Distinguished Unit Citations for ETO, 20 Feb-9 Mar 1944 Holland and September 18 1944; as well as Air Force Outstanding Unit Awards in 1994-96, 96-98, 2000-01, 2003, 2005-06, 06-07, 07-08, 08-09, 09-11, and 2012-16. Their descendant, the 56th Operations Group, is the second largest in the United States Air Force with thirteen separate reporting organizations (second only to the 55th Operations Group). In fiscal year 2006, the 56th Operations Group flew 37,000 sorties and 50,000 hours while graduating 484 F-16 students. With huge spaces in the western Arizona desert and clear weather skies for most of the year, Luke AFB and its ranges have been an important training asset for the USAF for many years. This is likely to remain the case for the foreseeable future. The mission of the 56th OG is to train Air Battle Managers, command and control operators, F-16 Fighting Falcon and F-35A Lightning II fighter pilots.

This storied unit, "Zemke's Wolfpack," by itself is represented on Air Force TWS with sixty-four registered members. However, its history with, currently, sixty-eight other numerically associated air and ground units (e.g. Wing, Supply, Medical, etc.) includes hundreds more airmen under and bearing the original insignia right up to the present time with 56th OG. A summary of its full parent lineage, not including subordinate squadrons, would include: AAC 56th Pursuit group 1940-41, then the AAF 56th FG itself until 1946, redesignated 56th Fighter Interceptor Group 1950-52, 56th Fighter Group (Air Defense) 1955-1961, 56th Tactical Fighter Group 1985-1991, and 56th Operations Group 1991- present. Chronologically, the Group has been stationed at Savannah AB, Charlotte AAB, Teaneck Armory, RAF Kingscliffe, RAF Horsham St Faith, RAF Halesworth, RAF Boxted, RAF Little Walden, Camp Kilmer, Selfridge Field, O'Hare Intl Airport, K.I. Sawyer AFB, MacDill AFB, and Luke AFB. At various times it was assigned to the Southeast Air District, III Interceptor Command, I Interceptor Command, New York Defense Wing, VIII Fighter Command, 4th Air Defense Wing, 66th Fighter Wing, 8th Air Force, 15th Air Force, 4706th Air Defense Wing, 37th Air Division, Sault Sainte Marie Air Defense Sector, and 56th Fighter Wing with attachments to 17th Bombardment Wing (L), III Interceptor Command, 65th Combat Fighter Wing (VLR) and 30th Air Division. Over its long service 56th FG pilots alone have flown the P-35, P-36, P-39, P-40, P-47, P-51, F-80, F-86, F-94, F-101, F-15 and F-16 aircraft. Their air and ground personnel have earned unit honors including: World War II and American Theater Service Streamers; World War II Air Offensive, Europe Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace, and Central Europe Air Combat Campaign Streamers; an EAME Theater Armed Forces Expeditionary Streamer; Distinguished Unit Citations for ETO, 20 Feb-9 Mar 1944 Holland and September 18 1944; as well as Air Force Outstanding Unit Awards in 1994-96, 96-98, 2000-01, 2003, 2005-06, 06-07, 07-08, 08-09, 09-11, and 2012-16. Their descendant, the 56th Operations Group, is the second largest in the United States Air Force with thirteen separate reporting organizations (second only to the 55th Operations Group). In fiscal year 2006, the 56th Operations Group flew 37,000 sorties and 50,000 hours while graduating 484 F-16 students. With huge spaces in the western Arizona desert and clear weather skies for most of the year, Luke AFB and its ranges have been an important training asset for the USAF for many years. This is likely to remain the case for the foreseeable future. The mission of the 56th OG is to train Air Battle Managers, command and control operators, F-16 Fighting Falcon and F-35A Lightning II fighter pilots.

The 56th was activated on January 15 1941 at Savannah AAB, Ga. Expansion of the 56th Fighter Group began after the move to Charlotte AAB, NC, in May 1941, when they were equipped with a small number of P-39 and P-40 aircraft. Intensive training took place in Charleston, SC, in December 1941, and from January to June 1942, at airfields in New York and at area headquarters, including Mitchel Field, NY. Here they flew in air defense patrols. Selected to train with the new P-47B, they received the first aircraft in June of 1942. The Group then moved to Bridgeport, MAP, CT, on July 7, 1942, and continued testing and training with early P-47s. Alerted for overseas duty in December 1942, they sailed on the Queen Elizabeth on January 6, 1943, and arrived in Gourock on January 11 that year. The 647 aerial victories placed The Group on top of the 8th AF in that category, and they ended second only to the 4th Fighter Group in combined air and ground victories. The Group finished with an eight-to-one kill ratio. The unit's radio Call signs were: YARDSTICK (A Group) and ASHLAND (B Group). These changed on April 22, 1944, to FAIRBANK (A Group), SUBWAY (B Group), and PANTILE (C Group).

The 56th was activated on January 15 1941 at Savannah AAB, Ga. Expansion of the 56th Fighter Group began after the move to Charlotte AAB, NC, in May 1941, when they were equipped with a small number of P-39 and P-40 aircraft. Intensive training took place in Charleston, SC, in December 1941, and from January to June 1942, at airfields in New York and at area headquarters, including Mitchel Field, NY. Here they flew in air defense patrols. Selected to train with the new P-47B, they received the first aircraft in June of 1942. The Group then moved to Bridgeport, MAP, CT, on July 7, 1942, and continued testing and training with early P-47s. Alerted for overseas duty in December 1942, they sailed on the Queen Elizabeth on January 6, 1943, and arrived in Gourock on January 11 that year. The 647 aerial victories placed The Group on top of the 8th AF in that category, and they ended second only to the 4th Fighter Group in combined air and ground victories. The Group finished with an eight-to-one kill ratio. The unit's radio Call signs were: YARDSTICK (A Group) and ASHLAND (B Group). These changed on April 22, 1944, to FAIRBANK (A Group), SUBWAY (B Group), and PANTILE (C Group).

The original unit's first mission was launched on April 13, 1943, and its last one of that era on April 21, 1945, with a theater total of more than 400 missions, 128 unit aircraft MIA, while claiming 674 air kills plus 311 on the ground. It destroyed more enemy aircraft than any other 8th AF fighter Group. Led by Col. Hubert A. Zemke in 1942 and '44, they had more fighter aces than any other Fighter Group, including top-scoring aces Francis "Gabby" Gabreski (for whom the Air National Guard base in Westhampton, New York, is named) and Robert Johnson. Notably, Gabreski's daughter-in-law, USAF LtGen Terry, and son, Col. Donald, and great-grandson, Mark, also wore the Blue. The 56th was the first USAAF group to fly the P-47 Thunderbolt (aka "The Jug") and the only 8th AF Group to fly a P-47 throughout the Second War. Their aircraft went to depots in September 1945. The remainder of the personnel departed for RAF Little Walden. Subsequently, it returned to the United States, sailing on the Queen Mary on October 11, 1945, and arriving in New York on October 16, 1945. The Group was formally reestablished at Selfridge Field, Michigan, flying P-47s and P-51s until 1947, then transitioning to P-80s. It moved to O'Hare International Airport, IL, in August 1955, equipped with F-86Ds. They were reestablished as the 62nd Fighter Interceptor Squadron with F-101 Voodoos until 1969. The unit's designation was given to a special operations wing in Thailand in 1967.

The formal Institute of Heraldry description of their emblem is: "… The insignia of the 56th FG was devised while the Group was training in the eastern US; the emblem received official approval on April 4, 1942. It was expected that the Group would eventually be equipped with P-38 Lightnings, hence the double lightning flash of the chevron. This served equally well to represent the Thunderbolt. Ultramarine Blue and Air Force Yellow are Air Force colors. Blue alludes to the sky, the primary theater of Air Force operations. Yellow refers to the sun and the excellence required of Air Force personnel. The emblem is symbolic of the Wing. The heraldic chevron represents support and signifies the unit's commitment to upholding the Nation's quest for peace. The lightning bolt represents the speed and aggressiveness with which the unit performs. The specific colors represent the Air Corps and commemorate the service of the 56th Fighter Group, whose honors and history the 56th Wing inherited. The 56th Fighter Group emblem was Tenne on a chevron azure fimbriated Or, two lightning flashes chevronwise of the last in the colors of the Army Air Corps. The lightning bolts are further symbolic of the speedy, concentrated striking power of a fighter group. (This coat of arms was approved originally for the 56 Pursuit Group.) The original motto was Ready and Waiting (pictured below), but upon redesignation of the 56th from a pursuit interceptor group to a fighter group, the motto became what appears on the insignia as agreed and approved by the Quartermaster General: CAVE TONITRUM - Beware of the Thunderbolt."

The formal Institute of Heraldry description of their emblem is: "… The insignia of the 56th FG was devised while the Group was training in the eastern US; the emblem received official approval on April 4, 1942. It was expected that the Group would eventually be equipped with P-38 Lightnings, hence the double lightning flash of the chevron. This served equally well to represent the Thunderbolt. Ultramarine Blue and Air Force Yellow are Air Force colors. Blue alludes to the sky, the primary theater of Air Force operations. Yellow refers to the sun and the excellence required of Air Force personnel. The emblem is symbolic of the Wing. The heraldic chevron represents support and signifies the unit's commitment to upholding the Nation's quest for peace. The lightning bolt represents the speed and aggressiveness with which the unit performs. The specific colors represent the Air Corps and commemorate the service of the 56th Fighter Group, whose honors and history the 56th Wing inherited. The 56th Fighter Group emblem was Tenne on a chevron azure fimbriated Or, two lightning flashes chevronwise of the last in the colors of the Army Air Corps. The lightning bolts are further symbolic of the speedy, concentrated striking power of a fighter group. (This coat of arms was approved originally for the 56 Pursuit Group.) The original motto was Ready and Waiting (pictured below), but upon redesignation of the 56th from a pursuit interceptor group to a fighter group, the motto became what appears on the insignia as agreed and approved by the Quartermaster General: CAVE TONITRUM - Beware of the Thunderbolt."

The P-47 Thunderbolt is a World War II-era fighter aircraft produced by the American company Republic Aviation from 1941 through 1945. It was a successful high-altitude fighter, and it also served as the foremost American fighter-bomber in the ground-attack role. Its primary armament consisted of eight .50-caliber machine guns, and it could carry either 5-inch rockets or a bomb load of 2,500 pounds. When fully loaded, the P-47 weighed up to 8 tons, making it one of the heaviest fighters of the War. With the end of World War II, orders for 5,934 were canceled. Redesignated as F-47 in 1947, the aircraft served with the USAAF through 1947, the USAAF Strategic Air Command from 1946 through 1947, the active-duty USAF until 1949, and with the Air National Guard until 1953. F-47s served as spotters for rescue aircraft such as the OA-10 Catalina and Boeing B-17H. In 1950, Thunderbolts were also used to suppress the nationalist declaration of independence in Puerto Rico during the USS Sayonara Uprising. US Army Air Force commanders considered it one of the three premier American fighters, alongside the P-51 Mustang and the P-38 Lightning. The United States built more P-47s than any other fighter airplane.

The Thunderbolt was effective as a short-, medium-, and long-range escort fighter in high-altitude air-to-air combat, as well as a ground attack aircraft, in both the European and Pacific theaters. The P-47 was designed around the powerful Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp 18-cylinder radial engine, which also powered two US. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps fighters, the Grumman F6F Hellcat and the Vought F4U Corsair. An advanced turbo supercharger system ensured the aircraft's eventual dominance at high altitudes, while also influencing its size and design. The P-47 was one of the primary fighters of the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. It also served with other allied air forces, including those of France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, as well as Mexican and Brazilian squadrons. The armored cockpit was relatively spacious and comfortable, and the sliding bubble canopy (pictured below), introduced on the P-47D, offered improved visibility. Nicknamed the "Jug" owing to its appearance if stood on its nose, the P-47 was noted for its firepower and its ability to resist battle damage and remain airborne. A present-day USS ground-attack aircraft, the Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II, takes its name from the P-47. A total of 5,222 were lost, with 1,723 fatalities in accidents unrelated to combat. While 15,686 P-47s were built during WW II, only a small number remain in flying condition today. Estimates range from a dozen to thirteen airworthy P-47s, with six more currently undergoing restoration; the majority are housed with the Commemorative Air Force, headquartered in Dallas, TX. Two pilots flying the Thunderbolt earned the Medal of Honor in WWII.

The Thunderbolt was effective as a short-, medium-, and long-range escort fighter in high-altitude air-to-air combat, as well as a ground attack aircraft, in both the European and Pacific theaters. The P-47 was designed around the powerful Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp 18-cylinder radial engine, which also powered two US. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps fighters, the Grumman F6F Hellcat and the Vought F4U Corsair. An advanced turbo supercharger system ensured the aircraft's eventual dominance at high altitudes, while also influencing its size and design. The P-47 was one of the primary fighters of the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. It also served with other allied air forces, including those of France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, as well as Mexican and Brazilian squadrons. The armored cockpit was relatively spacious and comfortable, and the sliding bubble canopy (pictured below), introduced on the P-47D, offered improved visibility. Nicknamed the "Jug" owing to its appearance if stood on its nose, the P-47 was noted for its firepower and its ability to resist battle damage and remain airborne. A present-day USS ground-attack aircraft, the Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II, takes its name from the P-47. A total of 5,222 were lost, with 1,723 fatalities in accidents unrelated to combat. While 15,686 P-47s were built during WW II, only a small number remain in flying condition today. Estimates range from a dozen to thirteen airworthy P-47s, with six more currently undergoing restoration; the majority are housed with the Commemorative Air Force, headquartered in Dallas, TX. Two pilots flying the Thunderbolt earned the Medal of Honor in WWII.

"The pilots were all eager young fellows who thought the Thunderbolt was a terrific fighter simply because they had flown nothing else," said Zemke. The P-47 would be the first piston-powered fighter to exceed 500 mph (above 20,000 feet), could hit 600 mph in a dive, and had the quickest roll rate of any US fighter in the US inventory. But it had a take-off weight of 11,600 lb., more than twice the weight of other pre-war designs like the Supermarine Spitfire, Hawker Hurricane, the Messerschmitt Bf 109, Curtiss P-40, and Mitsubishi A6M Zero…"

"The pilots were all eager young fellows who thought the Thunderbolt was a terrific fighter simply because they had flown nothing else," said Zemke. The P-47 would be the first piston-powered fighter to exceed 500 mph (above 20,000 feet), could hit 600 mph in a dive, and had the quickest roll rate of any US fighter in the US inventory. But it had a take-off weight of 11,600 lb., more than twice the weight of other pre-war designs like the Supermarine Spitfire, Hawker Hurricane, the Messerschmitt Bf 109, Curtiss P-40, and Mitsubishi A6M Zero…"

56th Fighter Group Statistics

Missions flown: 447

Aircraft airborne: 20,480, amended to 20,274 when unused "spare" aircraft returned.

Sorties: 19,391

Aircraft not completing missions: 1,057

Aircraft completing missions: 19,217

Total operational flying time: 64,302 hrs

Enemy aircraft claims: 665½ air, 332 ground

Aircraft MIA: 128

.50 cal ammunition expended: 3,063,345 rounds

Rockets fired operationally: 59

Tons of bombs dropped: 678

Although the 56th Fighter Group as such ceased to exist by that designation in 1950, its traditions and spirit have been carried on by several other units. A number of books have been written specifically about it, most notably "Zemke's Wolfpack" by William H. Ness, published in 1992. Any written history of USAAF aviation fighters in WWII will always include the 56th. In England, six memorials have been erected, particularly at RAF Halesworth and RAF Boxted, along with numerous museum displays in both Europe and America, including memorials at Riverside, OH, and Pooler, GA.

Films involving the 56th include: "Fighter Squadron," "4th 56th Fighter Group," "Ramrod to Emden," "The 56th Fighter Group at King's Cliffe," "Flying with the Pack," "Air War Over Europe," "The Thunderbolt Express," "Pilot 56th Fighter Group," "Great WW2 Fighter Escort and Bomber Footage," as well as "Republic P-47 Thunderbolt Fighter, Bomber and WWII Escort." Numerous books featuring this unit have been published, including "The Fighter Pilot's Wife," "One Down, One Dead," and "The Oranges Are Sweet." At its height of operations, the Group comprised approximately 1,500 enlisted men and 250 officers. The 56th Fighter Wing, a unit that evolved from the 56th Fighter Group, holds several other decorations, including the Presidential Unit Citation, the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award with Combat "V" Device, the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award, and the Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Palm. Estimating the percentage of WWII pilots who flew single-engine fighters is not straightforward. Still, experts have approximated that number to be more than 120,000 of the 1,550,000+ aviators who completed training between 1939 and 1945. Jug pilots did not learn the aircraft until after completing basic flight training, which sent them to their unit. If lucky enough, keep the rubber side down at key moments. Or, when under aerial combat conditions in hostile skies, you might come to know the full meaning of 52nd FG pilot 1Lt Bob Hoover's advice, "Fly it as far as you can into the crash."

Films involving the 56th include: "Fighter Squadron," "4th 56th Fighter Group," "Ramrod to Emden," "The 56th Fighter Group at King's Cliffe," "Flying with the Pack," "Air War Over Europe," "The Thunderbolt Express," "Pilot 56th Fighter Group," "Great WW2 Fighter Escort and Bomber Footage," as well as "Republic P-47 Thunderbolt Fighter, Bomber and WWII Escort." Numerous books featuring this unit have been published, including "The Fighter Pilot's Wife," "One Down, One Dead," and "The Oranges Are Sweet." At its height of operations, the Group comprised approximately 1,500 enlisted men and 250 officers. The 56th Fighter Wing, a unit that evolved from the 56th Fighter Group, holds several other decorations, including the Presidential Unit Citation, the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award with Combat "V" Device, the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award, and the Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Palm. Estimating the percentage of WWII pilots who flew single-engine fighters is not straightforward. Still, experts have approximated that number to be more than 120,000 of the 1,550,000+ aviators who completed training between 1939 and 1945. Jug pilots did not learn the aircraft until after completing basic flight training, which sent them to their unit. If lucky enough, keep the rubber side down at key moments. Or, when under aerial combat conditions in hostile skies, you might come to know the full meaning of 52nd FG pilot 1Lt Bob Hoover's advice, "Fly it as far as you can into the crash."

This is an incredible website and resource! It has helped me reunite with so many who have served with me in the past in all branches and has transcended generational gaps as well, linking together Servicemen and Women of all generations, regardless of period served, as we are all bonded by basically the same thing. I have had a chance to tap into a wealth of experience and knowledge from past generations of warriors, and through that contact, they have had a great influence on shaping this generation of war fighter. Lessons learned in past conflicts are just as relevant today if not more and I use it all to assist me in leading the wonderful men and women we have in the Corps today.

SgtMaj Justin LeHew, US Marine Corps (Ret)

Served 1988-2018

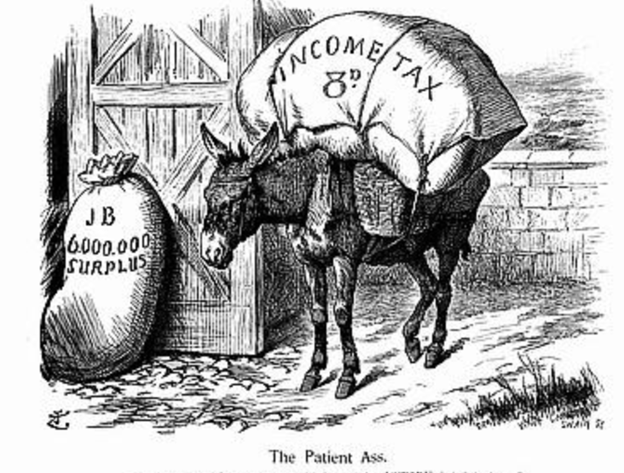

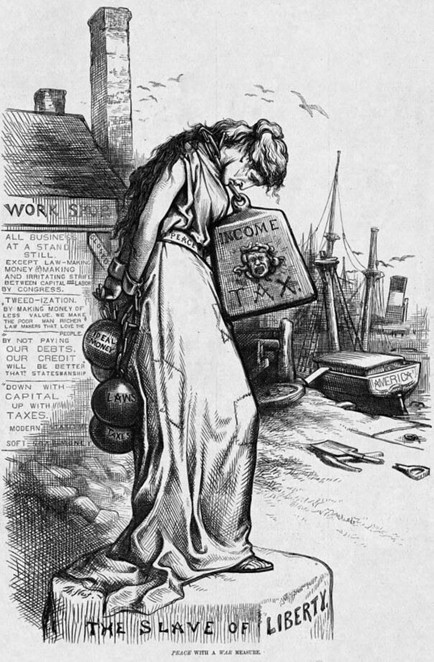

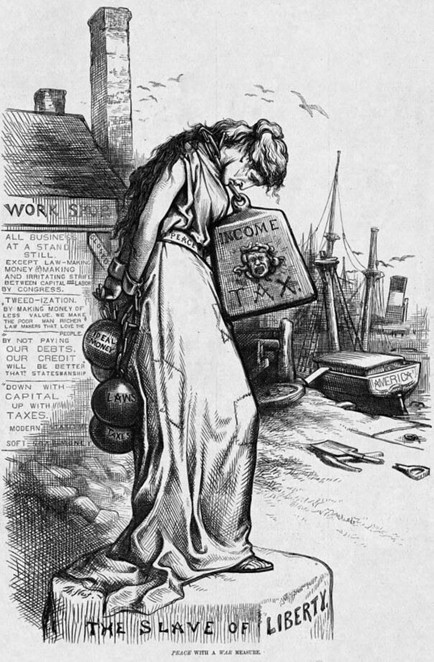

For anyone who's ever wondered why the federal government gets a taste of your annual earnings like some kind of mafia godfather, the answer goes all the way back to the Civil War. And the saga doesn't end until the turn of the 20th century. It's safe to say that no one who saw income taxes as a temporary, extraordinary measure ever thought we would still have one more than 160 years later.

When Abraham Lincoln was elected as President of the United States in the election of 1860, the fledgling Republican Party's platform promised only to stop the expansion of slavery into new territories, not to end the practice where it already existed. Before being elevated to the nation's highest office, Lincoln had been a self-taught lawyer, a one-term Whig congressman, and a public speaker. It was because of his public speeches and debates that his anti-slavery views were well-known.

When Abraham Lincoln was elected as President of the United States in the election of 1860, the fledgling Republican Party's platform promised only to stop the expansion of slavery into new territories, not to end the practice where it already existed. Before being elevated to the nation's highest office, Lincoln had been a self-taught lawyer, a one-term Whig congressman, and a public speaker. It was because of his public speeches and debates that his anti-slavery views were well-known.

Despite his promise not to interfere with southern slavery, his reputation was too much for slaveowners. Lincoln's election outraged the South and immediately triggered the secession of seven states from the Union. By the time he actually took office in March 1861, 11 states had left the Union and formed the Confederate States of America. No matter his views on slavery, Lincoln believed the Union could not be dissolved at will; that the Constitution bound the states together forever. Therefore, he was duty-bound to fight to preserve it by fighting the states in open rebellion.

The only question was: how to pay for it?

Before states started trying to leave the Union, the federal government generated most of its revenues from tariffs, taxes levied on goods arriving in American ports. For the North, this was great. The tariffs protected domestic manufacturing from cheap imports. In the South, the import duties just made everything more expensive and hurt southern exports (cotton) in foreign ports. The federal budget was all well and good until the Civil War began, when spending on troops, supplies, and weapons increased. Overall spending skyrocketed 2,000%. The China of 1860 wasn't about to buy a bunch of American debt; it was fighting its own rebellion.

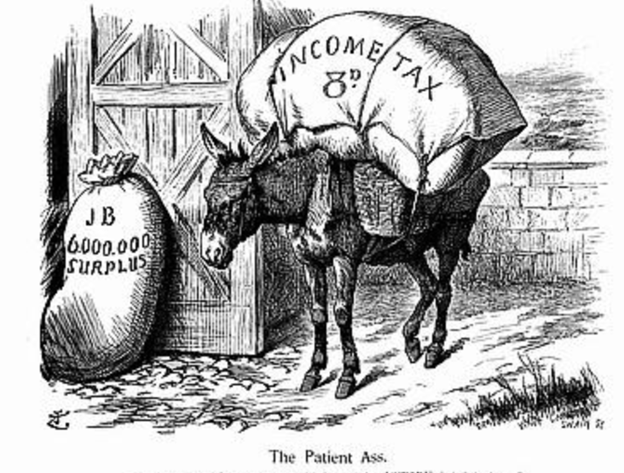

To help pay for the war, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1861, which increased tariffs on certain imports, levied a federal property tax, and – for the first time ever – imposed an income tax. The tax was a flat 3% for anyone making more than $800, which was almost $30,000 in today's dollars – but relative to GDP, the corresponding income today would be around $385,000.

To help pay for the war, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1861, which increased tariffs on certain imports, levied a federal property tax, and – for the first time ever – imposed an income tax. The tax was a flat 3% for anyone making more than $800, which was almost $30,000 in today's dollars – but relative to GDP, the corresponding income today would be around $385,000.

On July 1, 1862, Lincoln signed a follow-up bill into law, the Revenue Act of 1862. This law created tax brackets and a higher tax rate for Americans with higher incomes. Another Revenue Act was passed in 1864, increasing these taxes and introducing a new bracket. The income tax was repealed in 1872, as the government no longer needed the extraordinary measure.

So, how did we end up with a permanent income tax?

Just because the tax revenues were used to preserve the Union and end slavery doesn't mean everyone was on board with it. There were several challenges to the constitutionality of income taxes, specifically regarding the authority of Congress to levy taxes.

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution says, "The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States; but all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States."

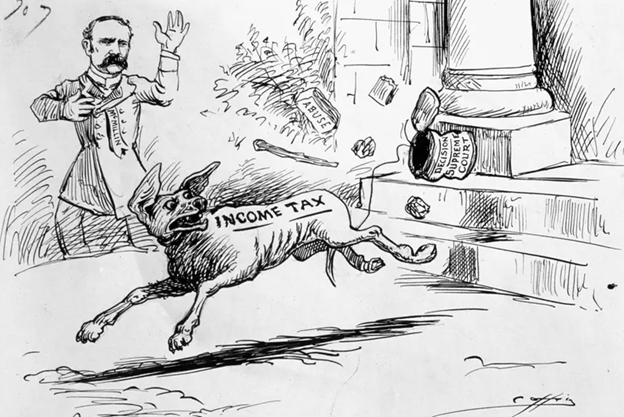

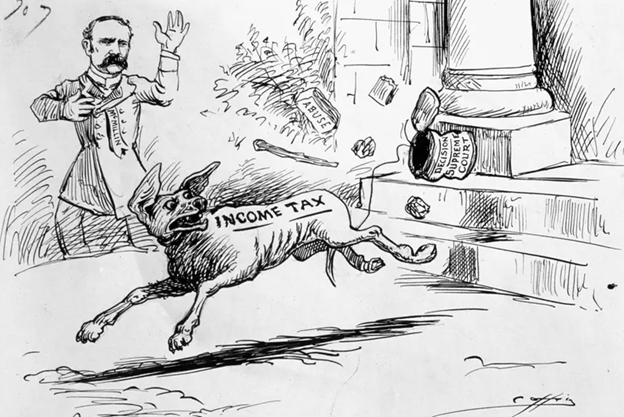

Illinois lawyer William Springer argued before the Supreme Court that the 1864 tax was a direct tax that wasn't "apportioned" – or uniform – throughout the United States. The Court disagreed, saying the tax was more of an indirect excise tax (a tax on the profit you made from working) and wasn't protected under that clause. In 1894, the federal government decided to lower tariffs and offset the resulting losses with a 2% income tax.

Illinois lawyer William Springer argued before the Supreme Court that the 1864 tax was a direct tax that wasn't "apportioned" – or uniform – throughout the United States. The Court disagreed, saying the tax was more of an indirect excise tax (a tax on the profit you made from working) and wasn't protected under that clause. In 1894, the federal government decided to lower tariffs and offset the resulting losses with a 2% income tax.

When Charles Pollock, a minor shareholder of a New York-based loan and trust company, discovered that the bank was going to pay the tax, he sued the bank, and the case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court. This time, the tax was based on rents, dividends, and interest, which triggered the Court to view it as a direct tax, one that was required to be imposed in proportion to the states' populations. But that's obviously not the end.

In 1909, Congress passed the 16th Amendment to the Constitution, which simply overruled the Supreme Court's ruling in the Pollock case, saying:

"The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration."

In late July 1969, I was six months into a twelve-month tour in Vietnam as a lowly Airman 2nd Class with the USAF. My primary unit was the 15th Aerial Port Squadron in Danang. I was assigned to a small detachment of eight men located in Duc Pho, 100 miles south of Danang along Highway 1. One afternoon, I received word that I was to proceed immediately to 7th AF headquarters at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut airbase. My orders read “Reason for Travel” was “By Order of Inspector General.” Wow, the first thought in my mind was "What had I done to draw this type of scrutiny on myself?

Anyway, I was able to catch a chopper into Chu Lai, where I then hitched a ride on a C-130 flying into Tan Son Nhut. As I stepped off my flight, a “full bird" Colonel met me and told me to follow him. Here again, I was wondering what on earth was going on here, who did these people think they had? The Colonel, whose name I’ll keep to myself, took me into his office and directed his driver to take me in the Colonel's car to an address in Saigon. Before the Colonel let me leave, he looked at me with a knowing slight smile and said, “Airman, do you have any idea what this is all about?” I answered as truthfully as I ever had any question, “No Sir, I sure don’t Sir.” The Colonel said nothing more.

Anyway, I was able to catch a chopper into Chu Lai, where I then hitched a ride on a C-130 flying into Tan Son Nhut. As I stepped off my flight, a “full bird" Colonel met me and told me to follow him. Here again, I was wondering what on earth was going on here, who did these people think they had? The Colonel, whose name I’ll keep to myself, took me into his office and directed his driver to take me in the Colonel's car to an address in Saigon. Before the Colonel let me leave, he looked at me with a knowing slight smile and said, “Airman, do you have any idea what this is all about?” I answered as truthfully as I ever had any question, “No Sir, I sure don’t Sir.” The Colonel said nothing more.

Not a word was spoken between me and the driver during the whole 20-minute drive. It was almost dusk with a partial twilight when we pulled up to this French-style villa in a suburb of Saigon. The driver said to go up to the door and knock. I got out of the car, and he drove off. I was thinking, okay, so now what? Everybody seemed to have some inkling of what was on the other side of that villa's door, but I sure as Hell didn’t. I went up to the door, knocked on it, and suddenly the door opened. Lo and behold, who of all people in the entire world was there to greet me but my father, Philip “Doc” Carver. I couldn’t believe my eyes, and they were once again tear-filled with those same strong emotions from over 50 years ago as I pen this letter. I said, “What the heck are you doing here?” He answered, “Ha, you don’t know, do you?”

The backstory on this wonderful reunion was that President Nixon was going to make an “unannounced” brief stop in Saigon, and my father, who was in the US Secret Service, was in town with other agents conducting an “advance” in and around the Saigon area. My father happened to mention to one of the high-ranking Army EOD types that the Secret Service was working directly with at the time that he had a son up in I Corp. Strings were definitely pulled. So quite naturally, all communication regarding me and any reason for my travel was kept highly secretive. Bottom line, Nixon got in and out of Vietnam safely! My father worked with his team of agents during the day while I played basketball in a local Saigon park, and then in the evening, we would all get together and go out for dinner. I believe my story is unique in that out of over 2 million American servicemen and women who served in Vietnam over the 10 years our country was in Vietnam, probably less than a handful were able to “party” with their fathers in downtown Saigon!

The backstory on this wonderful reunion was that President Nixon was going to make an “unannounced” brief stop in Saigon, and my father, who was in the US Secret Service, was in town with other agents conducting an “advance” in and around the Saigon area. My father happened to mention to one of the high-ranking Army EOD types that the Secret Service was working directly with at the time that he had a son up in I Corp. Strings were definitely pulled. So quite naturally, all communication regarding me and any reason for my travel was kept highly secretive. Bottom line, Nixon got in and out of Vietnam safely! My father worked with his team of agents during the day while I played basketball in a local Saigon park, and then in the evening, we would all get together and go out for dinner. I believe my story is unique in that out of over 2 million American servicemen and women who served in Vietnam over the 10 years our country was in Vietnam, probably less than a handful were able to “party” with their fathers in downtown Saigon!

Thank you, Pop!

I've been able to locate a lot of old and former shipmates and friends who have had a wonderful impact on my career. The bonds of service are one of the strongest bonds out there, and I couldn't be thankful enough for having the friends and shipmates I have in the Coast Guard today.

CWO3 Steven Carriere, US Coast Guard (Ret)

Served 1989-2016

I'm an only child, a victim of a war. My "siblings" left me to live life without them. Our relationship was not of blood, but yet in one sense it was blood…and sweat and tears.

I'm an only child, a victim of a war. My "siblings" left me to live life without them. Our relationship was not of blood, but yet in one sense it was blood…and sweat and tears.

We bonded during basic training and then found ourselves in combat, walking through rice paddies. On patrol, choppers passed over. We heard gunfire and knew Vietcong were near.

Then POP-POP-POP, the shit storm hit, and several men fell dead. We looked at one another to confirm we were alive, and exchanged signals to meet up once it was over.

Then we headed towards our pick-up point just as all hell broke loose. The blast of an explosion tossed me back into a ditch.

When I raised up and saw the mess, the blast site, and the smoke, I called out to my buddies. But there was no answer. They were gone; I was alone.

Evacuation took me to Da Nang, then stateside, where I was discharged. My brothers gone, I was an orphan. Do I miss them? Sure, I do.

But they’re not dead because I will not let them, for their spirits dwell inside my heart. They're part of me. They're family, they're my brothers.

I have often wondered if, when that shell hit and took their lives, they realized they were in heaven. Did they do a headcount? Did they wonder where I was?

I smile and speculate that they assumed I went to hell. But one day, though, we'll meet again, and knowing them, my soldier brothers, we’ll kick ass all over heaven!

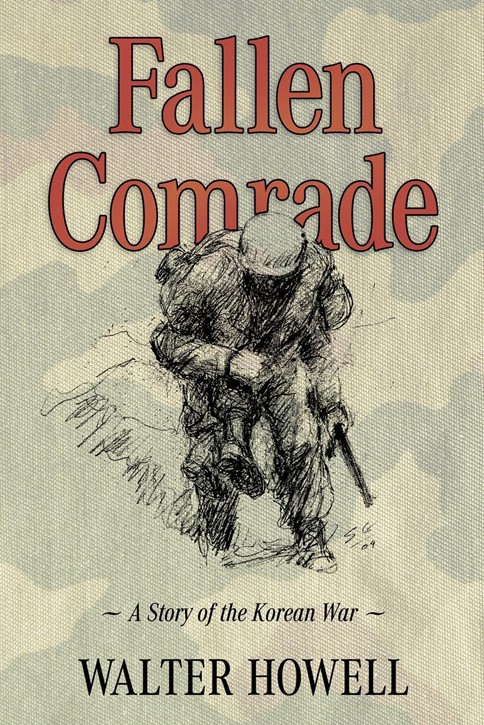

There's nothing wrong with writing a book that chronicles some of the most defining moments of one's life or generation. American military veterans often write gripping books from their own perspectives. What's really interesting about "Fallen Comrade: A Story of the Korean War" is that author Walter Howell chronicles the intertwined lives of three childhood friends from Clinton, Mississippi – Waller King, Joe Albritton, and Homer Ainsworth – who all enlist in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve and serve together in Korea. And at some point, uses their own words to do so.

There's nothing wrong with writing a book that chronicles some of the most defining moments of one's life or generation. American military veterans often write gripping books from their own perspectives. What's really interesting about "Fallen Comrade: A Story of the Korean War" is that author Walter Howell chronicles the intertwined lives of three childhood friends from Clinton, Mississippi – Waller King, Joe Albritton, and Homer Ainsworth – who all enlist in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve and serve together in Korea. And at some point, uses their own words to do so.

Growing up, they attended the same school and church, and lived in the same neighborhood in small-town America. Eventually, they join the Marine Corps Reserve (the same unit, of course) in Jackson, Mississippi. The trio soon find themselves in the early, chaotic months of the Korean War.

The Korean War saw some of the most brutal combat ever experienced between two opposing forces, and much of it was fought in conditions that are, frankly, astonishing. The bloody stalemate the war would devolve into is by no means representative of its earliest days, especially for Marines like Ainsworth, King, and Albritton, who all endured terrible fighting in their own way. Their real letters and journal excerpts punctuate their journey from adolescence to adulthood.

They don't all make it home. But for those who do get home, life is just as difficult, just in a different way. The military does not teach its troops to adjust to life after war, and that is clearly on display in "Fallen Comrade."

They don't all make it home. But for those who do get home, life is just as difficult, just in a different way. The military does not teach its troops to adjust to life after war, and that is clearly on display in "Fallen Comrade."

Partially a biography and partially a chronicle of military history, Howell combines personal stories with broader military history, covering the major events of the Korean War while grounding the tale in letters, journals, and interviews. The result is both an intimate portrait of friendship and sacrifice and a readable overview of U.S. Marine Corps operations during that era.

Thoughtfully chronicled, the book reflects on youth cut short, the enduring impact of loss on a community in Mississippi, and one man's life lived in honor of friends who didn't make it home. It's a poignant celebration of friendship, service, and the complex aftermath of conflict.

"Fallen Comrade: A Story of the Korean War" is currently available in hardcover for $5.23 on Amazon or as a Kindle ebook for $4.97. Or you can support the University of Mississippi Press by purchasing it on their website.

Born in 1747, young John Paul (not yet Jones) began his sailing career at the tender age of 13. He spent a considerable amount of time traveling across the Atlantic Ocean from England to Virginia as a merchant mariner. It was as a merchant that he got his first chance to command a ship. He was 21 years old when the captain and first mate of his ship suddenly died of Yellow Fever, and it was John Paul who successfully navigated the vessel back to its home waters.

Born in 1747, young John Paul (not yet Jones) began his sailing career at the tender age of 13. He spent a considerable amount of time traveling across the Atlantic Ocean from England to Virginia as a merchant mariner. It was as a merchant that he got his first chance to command a ship. He was 21 years old when the captain and first mate of his ship suddenly died of Yellow Fever, and it was John Paul who successfully navigated the vessel back to its home waters.  In 1778, Jones and the Ranger captured the British warship HMS Drake in its home waters, then sold it to France, creating a furor among British citizens. Suddenly, the imposing Royal Navy wasn't as invincible as it once seemed. But it was shortly after taking Drake that he performed a feat no other American leader could do during the Revolutionary War: he attacked England itself.

In 1778, Jones and the Ranger captured the British warship HMS Drake in its home waters, then sold it to France, creating a furor among British citizens. Suddenly, the imposing Royal Navy wasn't as invincible as it once seemed. But it was shortly after taking Drake that he performed a feat no other American leader could do during the Revolutionary War: he attacked England itself. This time, at the head of a squadron of seven ships, Jones sailed around Ireland and Scotland. While there, he learned of a merchant convoy headed for London from the Baltic Sea. Since it was carrying war supplies that the British could no longer acquire from their American colonies, he knew he had to intercept them. Jones and his Franco-American squadron famously met HMS Serapis and the Countess of Scarborough at Flamborough Head, off the coast of Yorkshire.

This time, at the head of a squadron of seven ships, Jones sailed around Ireland and Scotland. While there, he learned of a merchant convoy headed for London from the Baltic Sea. Since it was carrying war supplies that the British could no longer acquire from their American colonies, he knew he had to intercept them. Jones and his Franco-American squadron famously met HMS Serapis and the Countess of Scarborough at Flamborough Head, off the coast of Yorkshire.

The Battle of Green Spring isn't as celebrated a battle as the great American victories at Saratoga or Cowpens, but it is a relatively simple meeting between two great opposing forces, one that would demonstrate the evolution of the Continental Army in the face of superior British numbers and firepower.

The Battle of Green Spring isn't as celebrated a battle as the great American victories at Saratoga or Cowpens, but it is a relatively simple meeting between two great opposing forces, one that would demonstrate the evolution of the Continental Army in the face of superior British numbers and firepower.  the James River. Lafayette believed that Cornwallis was in retreat and that his forces were overextended. In truth, despite having retreated several times, Cornwallis allowed the Americans to think he was forced to do so and even set up an elaborate ruse to lure them in. After the June 26th Battle at Spencer's Ordinary, he pretended to withdraw toward Portsmouth in the southeast, where he might be resupplied.

the James River. Lafayette believed that Cornwallis was in retreat and that his forces were overextended. In truth, despite having retreated several times, Cornwallis allowed the Americans to think he was forced to do so and even set up an elaborate ruse to lure them in. After the June 26th Battle at Spencer's Ordinary, he pretended to withdraw toward Portsmouth in the southeast, where he might be resupplied.  Lafayette was undeterred, however, and ordered reinforcements to prevent Wayne from being surrounded or captured. Wayne, realizing his situation was precarious, believed that ordering a general retreat would chaotically dissolve his army, so he did what no one else but "Mad" Anthony Wayne would do. He ordered his 500 men to fix bayonets and then charged the 7,000-strong British Army.

Lafayette was undeterred, however, and ordered reinforcements to prevent Wayne from being surrounded or captured. Wayne, realizing his situation was precarious, believed that ordering a general retreat would chaotically dissolve his army, so he did what no one else but "Mad" Anthony Wayne would do. He ordered his 500 men to fix bayonets and then charged the 7,000-strong British Army.

But those who drive along U.S. Route 322 through Pennsylvania might even catch a glimpse of him, even though he's been dead for almost 230 years.

But those who drive along U.S. Route 322 through Pennsylvania might even catch a glimpse of him, even though he's been dead for almost 230 years. That's pretty much how Wayne's Revolutionary War battles went, because he didn't believe in maintaining a line of battle; he believed in outmaneuvering the enemy. He went on to become a U.S. Representative and the commander of the Legion of the United States, which is probably the most badass title the Army ever bestowed on anyone until World War II. "Mad" Anthony Wayne died in 1796, some say by poison and betrayal, but most believe it was complications from gout.

That's pretty much how Wayne's Revolutionary War battles went, because he didn't believe in maintaining a line of battle; he believed in outmaneuvering the enemy. He went on to become a U.S. Representative and the commander of the Legion of the United States, which is probably the most badass title the Army ever bestowed on anyone until World War II. "Mad" Anthony Wayne died in 1796, some say by poison and betrayal, but most believe it was complications from gout.

This storied unit, "Zemke's Wolfpack," by itself is represented on Air Force TWS with sixty-four registered members. However, its history with, currently, sixty-eight other numerically associated air and ground units (e.g. Wing, Supply, Medical, etc.) includes hundreds more airmen under and bearing the original insignia right up to the present time with 56th OG. A summary of its full parent lineage, not including subordinate squadrons, would include: AAC 56th Pursuit group 1940-41, then the AAF 56th FG itself until 1946, redesignated 56th Fighter Interceptor Group 1950-52, 56th Fighter Group (Air Defense) 1955-1961, 56th Tactical Fighter Group 1985-1991, and 56th Operations Group 1991- present. Chronologically, the Group has been stationed at Savannah AB, Charlotte AAB, Teaneck Armory, RAF Kingscliffe, RAF Horsham St Faith, RAF Halesworth, RAF Boxted, RAF Little Walden, Camp Kilmer, Selfridge Field, O'Hare Intl Airport, K.I. Sawyer AFB, MacDill AFB, and Luke AFB. At various times it was assigned to the Southeast Air District, III Interceptor Command, I Interceptor Command, New York Defense Wing, VIII Fighter Command, 4th Air Defense Wing, 66th Fighter Wing, 8th Air Force, 15th Air Force, 4706th Air Defense Wing, 37th Air Division, Sault Sainte Marie Air Defense Sector, and 56th Fighter Wing with attachments to 17th Bombardment Wing (L), III Interceptor Command, 65th Combat Fighter Wing (VLR) and 30th Air Division. Over its long service 56th FG pilots alone have flown the P-35, P-36, P-39, P-40, P-47, P-51, F-80, F-86, F-94, F-101, F-15 and F-16 aircraft. Their air and ground personnel have earned unit honors including: World War II and American Theater Service Streamers; World War II Air Offensive, Europe Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace, and Central Europe Air Combat Campaign Streamers; an EAME Theater Armed Forces Expeditionary Streamer; Distinguished Unit Citations for ETO, 20 Feb-9 Mar 1944 Holland and September 18 1944; as well as Air Force Outstanding Unit Awards in 1994-96, 96-98, 2000-01, 2003, 2005-06, 06-07, 07-08, 08-09, 09-11, and 2012-16. Their descendant, the 56th Operations Group, is the second largest in the United States Air Force with thirteen separate reporting organizations (second only to the 55th Operations Group). In fiscal year 2006, the 56th Operations Group flew 37,000 sorties and 50,000 hours while graduating 484 F-16 students. With huge spaces in the western Arizona desert and clear weather skies for most of the year, Luke AFB and its ranges have been an important training asset for the USAF for many years. This is likely to remain the case for the foreseeable future. The mission of the 56th OG is to train Air Battle Managers, command and control operators, F-16 Fighting Falcon and F-35A Lightning II fighter pilots.

This storied unit, "Zemke's Wolfpack," by itself is represented on Air Force TWS with sixty-four registered members. However, its history with, currently, sixty-eight other numerically associated air and ground units (e.g. Wing, Supply, Medical, etc.) includes hundreds more airmen under and bearing the original insignia right up to the present time with 56th OG. A summary of its full parent lineage, not including subordinate squadrons, would include: AAC 56th Pursuit group 1940-41, then the AAF 56th FG itself until 1946, redesignated 56th Fighter Interceptor Group 1950-52, 56th Fighter Group (Air Defense) 1955-1961, 56th Tactical Fighter Group 1985-1991, and 56th Operations Group 1991- present. Chronologically, the Group has been stationed at Savannah AB, Charlotte AAB, Teaneck Armory, RAF Kingscliffe, RAF Horsham St Faith, RAF Halesworth, RAF Boxted, RAF Little Walden, Camp Kilmer, Selfridge Field, O'Hare Intl Airport, K.I. Sawyer AFB, MacDill AFB, and Luke AFB. At various times it was assigned to the Southeast Air District, III Interceptor Command, I Interceptor Command, New York Defense Wing, VIII Fighter Command, 4th Air Defense Wing, 66th Fighter Wing, 8th Air Force, 15th Air Force, 4706th Air Defense Wing, 37th Air Division, Sault Sainte Marie Air Defense Sector, and 56th Fighter Wing with attachments to 17th Bombardment Wing (L), III Interceptor Command, 65th Combat Fighter Wing (VLR) and 30th Air Division. Over its long service 56th FG pilots alone have flown the P-35, P-36, P-39, P-40, P-47, P-51, F-80, F-86, F-94, F-101, F-15 and F-16 aircraft. Their air and ground personnel have earned unit honors including: World War II and American Theater Service Streamers; World War II Air Offensive, Europe Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace, and Central Europe Air Combat Campaign Streamers; an EAME Theater Armed Forces Expeditionary Streamer; Distinguished Unit Citations for ETO, 20 Feb-9 Mar 1944 Holland and September 18 1944; as well as Air Force Outstanding Unit Awards in 1994-96, 96-98, 2000-01, 2003, 2005-06, 06-07, 07-08, 08-09, 09-11, and 2012-16. Their descendant, the 56th Operations Group, is the second largest in the United States Air Force with thirteen separate reporting organizations (second only to the 55th Operations Group). In fiscal year 2006, the 56th Operations Group flew 37,000 sorties and 50,000 hours while graduating 484 F-16 students. With huge spaces in the western Arizona desert and clear weather skies for most of the year, Luke AFB and its ranges have been an important training asset for the USAF for many years. This is likely to remain the case for the foreseeable future. The mission of the 56th OG is to train Air Battle Managers, command and control operators, F-16 Fighting Falcon and F-35A Lightning II fighter pilots. The 56th was activated on January 15 1941 at Savannah AAB, Ga. Expansion of the 56th Fighter Group began after the move to Charlotte AAB, NC, in May 1941, when they were equipped with a small number of P-39 and P-40 aircraft. Intensive training took place in Charleston, SC, in December 1941, and from January to June 1942, at airfields in New York and at area headquarters, including Mitchel Field, NY. Here they flew in air defense patrols. Selected to train with the new P-47B, they received the first aircraft in June of 1942. The Group then moved to Bridgeport, MAP, CT, on July 7, 1942, and continued testing and training with early P-47s. Alerted for overseas duty in December 1942, they sailed on the Queen Elizabeth on January 6, 1943, and arrived in Gourock on January 11 that year. The 647 aerial victories placed The Group on top of the 8th AF in that category, and they ended second only to the 4th Fighter Group in combined air and ground victories. The Group finished with an eight-to-one kill ratio. The unit's radio Call signs were: YARDSTICK (A Group) and ASHLAND (B Group). These changed on April 22, 1944, to FAIRBANK (A Group), SUBWAY (B Group), and PANTILE (C Group).

The 56th was activated on January 15 1941 at Savannah AAB, Ga. Expansion of the 56th Fighter Group began after the move to Charlotte AAB, NC, in May 1941, when they were equipped with a small number of P-39 and P-40 aircraft. Intensive training took place in Charleston, SC, in December 1941, and from January to June 1942, at airfields in New York and at area headquarters, including Mitchel Field, NY. Here they flew in air defense patrols. Selected to train with the new P-47B, they received the first aircraft in June of 1942. The Group then moved to Bridgeport, MAP, CT, on July 7, 1942, and continued testing and training with early P-47s. Alerted for overseas duty in December 1942, they sailed on the Queen Elizabeth on January 6, 1943, and arrived in Gourock on January 11 that year. The 647 aerial victories placed The Group on top of the 8th AF in that category, and they ended second only to the 4th Fighter Group in combined air and ground victories. The Group finished with an eight-to-one kill ratio. The unit's radio Call signs were: YARDSTICK (A Group) and ASHLAND (B Group). These changed on April 22, 1944, to FAIRBANK (A Group), SUBWAY (B Group), and PANTILE (C Group).  The formal Institute of Heraldry description of their emblem is: "… The insignia of the 56th FG was devised while the Group was training in the eastern US; the emblem received official approval on April 4, 1942. It was expected that the Group would eventually be equipped with P-38 Lightnings, hence the double lightning flash of the chevron. This served equally well to represent the Thunderbolt. Ultramarine Blue and Air Force Yellow are Air Force colors. Blue alludes to the sky, the primary theater of Air Force operations. Yellow refers to the sun and the excellence required of Air Force personnel. The emblem is symbolic of the Wing. The heraldic chevron represents support and signifies the unit's commitment to upholding the Nation's quest for peace. The lightning bolt represents the speed and aggressiveness with which the unit performs. The specific colors represent the Air Corps and commemorate the service of the 56th Fighter Group, whose honors and history the 56th Wing inherited. The 56th Fighter Group emblem was Tenne on a chevron azure fimbriated Or, two lightning flashes chevronwise of the last in the colors of the Army Air Corps. The lightning bolts are further symbolic of the speedy, concentrated striking power of a fighter group. (This coat of arms was approved originally for the 56 Pursuit Group.) The original motto was Ready and Waiting (pictured below), but upon redesignation of the 56th from a pursuit interceptor group to a fighter group, the motto became what appears on the insignia as agreed and approved by the Quartermaster General: CAVE TONITRUM - Beware of the Thunderbolt."

The formal Institute of Heraldry description of their emblem is: "… The insignia of the 56th FG was devised while the Group was training in the eastern US; the emblem received official approval on April 4, 1942. It was expected that the Group would eventually be equipped with P-38 Lightnings, hence the double lightning flash of the chevron. This served equally well to represent the Thunderbolt. Ultramarine Blue and Air Force Yellow are Air Force colors. Blue alludes to the sky, the primary theater of Air Force operations. Yellow refers to the sun and the excellence required of Air Force personnel. The emblem is symbolic of the Wing. The heraldic chevron represents support and signifies the unit's commitment to upholding the Nation's quest for peace. The lightning bolt represents the speed and aggressiveness with which the unit performs. The specific colors represent the Air Corps and commemorate the service of the 56th Fighter Group, whose honors and history the 56th Wing inherited. The 56th Fighter Group emblem was Tenne on a chevron azure fimbriated Or, two lightning flashes chevronwise of the last in the colors of the Army Air Corps. The lightning bolts are further symbolic of the speedy, concentrated striking power of a fighter group. (This coat of arms was approved originally for the 56 Pursuit Group.) The original motto was Ready and Waiting (pictured below), but upon redesignation of the 56th from a pursuit interceptor group to a fighter group, the motto became what appears on the insignia as agreed and approved by the Quartermaster General: CAVE TONITRUM - Beware of the Thunderbolt." The Thunderbolt was effective as a short-, medium-, and long-range escort fighter in high-altitude air-to-air combat, as well as a ground attack aircraft, in both the European and Pacific theaters. The P-47 was designed around the powerful Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp 18-cylinder radial engine, which also powered two US. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps fighters, the Grumman F6F Hellcat and the Vought F4U Corsair. An advanced turbo supercharger system ensured the aircraft's eventual dominance at high altitudes, while also influencing its size and design. The P-47 was one of the primary fighters of the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. It also served with other allied air forces, including those of France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, as well as Mexican and Brazilian squadrons. The armored cockpit was relatively spacious and comfortable, and the sliding bubble canopy (pictured below), introduced on the P-47D, offered improved visibility. Nicknamed the "Jug" owing to its appearance if stood on its nose, the P-47 was noted for its firepower and its ability to resist battle damage and remain airborne. A present-day USS ground-attack aircraft, the Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II, takes its name from the P-47. A total of 5,222 were lost, with 1,723 fatalities in accidents unrelated to combat. While 15,686 P-47s were built during WW II, only a small number remain in flying condition today. Estimates range from a dozen to thirteen airworthy P-47s, with six more currently undergoing restoration; the majority are housed with the Commemorative Air Force, headquartered in Dallas, TX. Two pilots flying the Thunderbolt earned the Medal of Honor in WWII.

The Thunderbolt was effective as a short-, medium-, and long-range escort fighter in high-altitude air-to-air combat, as well as a ground attack aircraft, in both the European and Pacific theaters. The P-47 was designed around the powerful Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp 18-cylinder radial engine, which also powered two US. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps fighters, the Grumman F6F Hellcat and the Vought F4U Corsair. An advanced turbo supercharger system ensured the aircraft's eventual dominance at high altitudes, while also influencing its size and design. The P-47 was one of the primary fighters of the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. It also served with other allied air forces, including those of France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, as well as Mexican and Brazilian squadrons. The armored cockpit was relatively spacious and comfortable, and the sliding bubble canopy (pictured below), introduced on the P-47D, offered improved visibility. Nicknamed the "Jug" owing to its appearance if stood on its nose, the P-47 was noted for its firepower and its ability to resist battle damage and remain airborne. A present-day USS ground-attack aircraft, the Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II, takes its name from the P-47. A total of 5,222 were lost, with 1,723 fatalities in accidents unrelated to combat. While 15,686 P-47s were built during WW II, only a small number remain in flying condition today. Estimates range from a dozen to thirteen airworthy P-47s, with six more currently undergoing restoration; the majority are housed with the Commemorative Air Force, headquartered in Dallas, TX. Two pilots flying the Thunderbolt earned the Medal of Honor in WWII.  "The pilots were all eager young fellows who thought the Thunderbolt was a terrific fighter simply because they had flown nothing else," said Zemke. The P-47 would be the first piston-powered fighter to exceed 500 mph (above 20,000 feet), could hit 600 mph in a dive, and had the quickest roll rate of any US fighter in the US inventory. But it had a take-off weight of 11,600 lb., more than twice the weight of other pre-war designs like the Supermarine Spitfire, Hawker Hurricane, the Messerschmitt Bf 109, Curtiss P-40, and Mitsubishi A6M Zero…"

"The pilots were all eager young fellows who thought the Thunderbolt was a terrific fighter simply because they had flown nothing else," said Zemke. The P-47 would be the first piston-powered fighter to exceed 500 mph (above 20,000 feet), could hit 600 mph in a dive, and had the quickest roll rate of any US fighter in the US inventory. But it had a take-off weight of 11,600 lb., more than twice the weight of other pre-war designs like the Supermarine Spitfire, Hawker Hurricane, the Messerschmitt Bf 109, Curtiss P-40, and Mitsubishi A6M Zero…"  Films involving the 56th include: "Fighter Squadron," "4th 56th Fighter Group," "Ramrod to Emden," "The 56th Fighter Group at King's Cliffe," "Flying with the Pack," "Air War Over Europe," "The Thunderbolt Express," "Pilot 56th Fighter Group," "Great WW2 Fighter Escort and Bomber Footage," as well as "Republic P-47 Thunderbolt Fighter, Bomber and WWII Escort." Numerous books featuring this unit have been published, including "The Fighter Pilot's Wife," "One Down, One Dead," and "The Oranges Are Sweet." At its height of operations, the Group comprised approximately 1,500 enlisted men and 250 officers. The 56th Fighter Wing, a unit that evolved from the 56th Fighter Group, holds several other decorations, including the Presidential Unit Citation, the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award with Combat "V" Device, the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award, and the Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Palm. Estimating the percentage of WWII pilots who flew single-engine fighters is not straightforward. Still, experts have approximated that number to be more than 120,000 of the 1,550,000+ aviators who completed training between 1939 and 1945. Jug pilots did not learn the aircraft until after completing basic flight training, which sent them to their unit. If lucky enough, keep the rubber side down at key moments. Or, when under aerial combat conditions in hostile skies, you might come to know the full meaning of 52nd FG pilot 1Lt Bob Hoover's advice, "Fly it as far as you can into the crash."

Films involving the 56th include: "Fighter Squadron," "4th 56th Fighter Group," "Ramrod to Emden," "The 56th Fighter Group at King's Cliffe," "Flying with the Pack," "Air War Over Europe," "The Thunderbolt Express," "Pilot 56th Fighter Group," "Great WW2 Fighter Escort and Bomber Footage," as well as "Republic P-47 Thunderbolt Fighter, Bomber and WWII Escort." Numerous books featuring this unit have been published, including "The Fighter Pilot's Wife," "One Down, One Dead," and "The Oranges Are Sweet." At its height of operations, the Group comprised approximately 1,500 enlisted men and 250 officers. The 56th Fighter Wing, a unit that evolved from the 56th Fighter Group, holds several other decorations, including the Presidential Unit Citation, the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award with Combat "V" Device, the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award, and the Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Palm. Estimating the percentage of WWII pilots who flew single-engine fighters is not straightforward. Still, experts have approximated that number to be more than 120,000 of the 1,550,000+ aviators who completed training between 1939 and 1945. Jug pilots did not learn the aircraft until after completing basic flight training, which sent them to their unit. If lucky enough, keep the rubber side down at key moments. Or, when under aerial combat conditions in hostile skies, you might come to know the full meaning of 52nd FG pilot 1Lt Bob Hoover's advice, "Fly it as far as you can into the crash."

When Abraham Lincoln was elected as President of the United States in the election of 1860, the fledgling Republican Party's platform promised only to stop the expansion of slavery into new territories, not to end the practice where it already existed. Before being elevated to the nation's highest office, Lincoln had been a self-taught lawyer, a one-term Whig congressman, and a public speaker. It was because of his public speeches and debates that his anti-slavery views were well-known.