Battlefield Chronicles: When Johnny Comes Marching Home

When war raged through Europe in the summer of 1914, the American public wanted nothing to do with it. Not our war, they said. President Woodrow Wilson agreed. He pledged neutrality for the United States. But over the next few years, three incidents turned public option away from isolationism to one of wanting to take action against Germany and its allies.

When war raged through Europe in the summer of 1914, the American public wanted nothing to do with it. Not our war, they said. President Woodrow Wilson agreed. He pledged neutrality for the United States. But over the next few years, three incidents turned public option away from isolationism to one of wanting to take action against Germany and its allies.

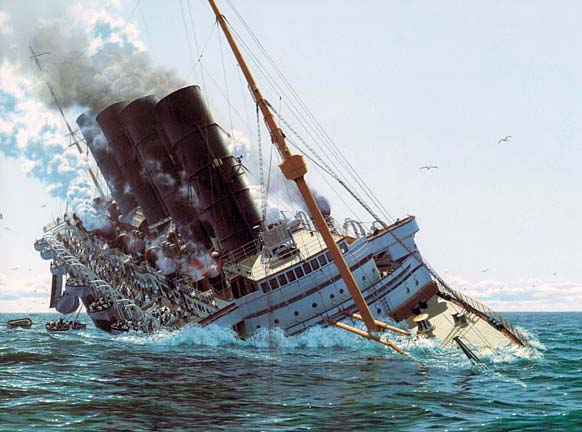

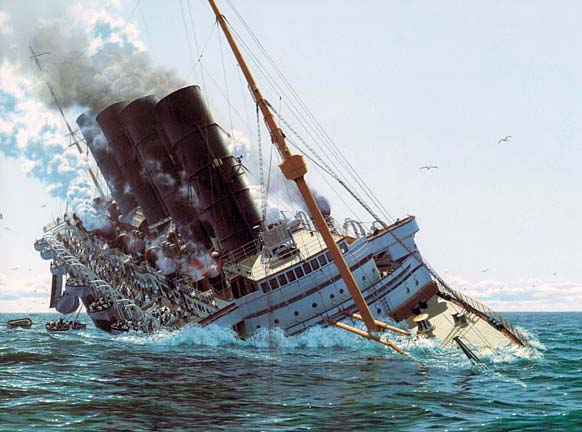

First was when a German submarine torpedoed the British-owned passenger liner Lusitania without warning, killing 1,2,00 passengers, including 128 Americans. Second, a German submarine sank an Italian liner without warning, killing 272 people, including 27 Americans.

The final straw was the Zimmermann Telegram, a 1917 coded diplomatic proposal from the German Empire for Mexico to join in a military alliance in the event the United States entered the war against Germany.  The telegram's main purpose was to make the Mexican government declare war on the

The telegram's main purpose was to make the Mexican government declare war on the  U.S., which would have tied down U.S. forces and slowed the export of U.S. arms to England, France, Russia, and their allies.

U.S., which would have tied down U.S. forces and slowed the export of U.S. arms to England, France, Russia, and their allies.

As part of the alliance, Germany claimed they would assist Mexico to reclaim Texas and the Southwest.

When the content of the message was decoded by British Intelligence and went public, Americans were outraged. President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress for "a war to end all wars" that would "make the world safe for democracy." Congress voted to declare war on April 6, 1917.

Mexico, far weaker than the U.S., ignored the proposal and, after the U.S. entered the war, officially rejected it.

By the time the Great War ended on November 11, 1918, more than 2 million American servicemen had served on the battlefields of Western Europe. Of those, 53,402 were killed in action, with another 63,114 deaths from disease and other causes. About 205,000 suffered wounds.

Those who returned home were treated like heroes. As some proudly marched all along Broadway, hundreds of thousands of spectators crowded the sidewalks, and others looked down from skyscraper windows. They cheered and shouted and tossed confetti in a shower that became a blizzard of shredded paper falling on the motorcade and the marching troops below. Flags, marching bands, and music heralded the procession. When the parades ended, and the fighting men and women were discharged, they returned home to farms, towns, and cities throughout America hoping to pick up life where they had left it. But the returning veterans found things had changed, including themselves. Those suffering from emotional and physical issues struggled to adjust. Those who lost the jobs they had before

Those who returned home were treated like heroes. As some proudly marched all along Broadway, hundreds of thousands of spectators crowded the sidewalks, and others looked down from skyscraper windows. They cheered and shouted and tossed confetti in a shower that became a blizzard of shredded paper falling on the motorcade and the marching troops below. Flags, marching bands, and music heralded the procession. When the parades ended, and the fighting men and women were discharged, they returned home to farms, towns, and cities throughout America hoping to pick up life where they had left it. But the returning veterans found things had changed, including themselves. Those suffering from emotional and physical issues struggled to adjust. Those who lost the jobs they had before  marching off to war found it difficult to find other work in an economy that was weakening by the day.

marching off to war found it difficult to find other work in an economy that was weakening by the day.

Aware of their plight, some legislators attempted to get bills passed that would assist veterans in getting their lives back together, but it never got off the ground.  Eventually, in 1924, six years after their service, Congress did pass a bill providing World War I veterans compensation for their service. But President Calvin Coolidge vetoed the bill, saying: "patriotism...bought and paid for is not patriotism."

Eventually, in 1924, six years after their service, Congress did pass a bill providing World War I veterans compensation for their service. But President Calvin Coolidge vetoed the bill, saying: "patriotism...bought and paid for is not patriotism."

Congress overrode his veto a few days later, enacting the World War Adjusted Compensation Act of 1924, commonly known as the Bonus Act, providing a bonus based on the number of days served. But there was a catch: most Veterans wouldn't see a dime for 20 years.

As years passed and the American economy grew worse, continued efforts by veterans groups to get the bonuses paid out sooner went nowhere. And although there was some Congressional support for the immediate redemption of the military service certificates,  President Hoover and Republican congressmen opposed such action; they reasoned that the government would have to increase taxes to cover the costs of the payout, and thus any potential recovery would be slowed.

President Hoover and Republican congressmen opposed such action; they reasoned that the government would have to increase taxes to cover the costs of the payout, and thus any potential recovery would be slowed.

As the Great Depression of 1929 worsened, hundreds of thousands of war veterans found it difficult to make a living. Many joined the groups already pressuring the government to pay  out the bonus immediately. It would help them get through the rough times, they pleaded. Their efforts fell on deaf ears. Neither President Herbert Hoover nor the Congress would budge.

out the bonus immediately. It would help them get through the rough times, they pleaded. Their efforts fell on deaf ears. Neither President Herbert Hoover nor the Congress would budge.

With the deepening of the depression, veterans and their families began marching on Washington D.C. in the spring and summer of 1932 to demand cash-payment redemption of their service certificates.

Thousands of war veterans began difficult journeys across the country, traveling in empty railroad freight cars, in the backs of trucks, in cars, on foot, and by any other means that became available.  By mid-June, it was estimated that as many as 20,000 veterans and some family members had arrived in Washington, and were camping out, often in dirty, unsanitary conditions, in parks around the city, depending on donations of food from a variety of governments, churches and private citizens. Most of the Bonus Army, as they became known, camped in a Hooverville on the Anacostia Flats, a swampy, muddy area across the Anacostia River from the federal core of Washington.

By mid-June, it was estimated that as many as 20,000 veterans and some family members had arrived in Washington, and were camping out, often in dirty, unsanitary conditions, in parks around the city, depending on donations of food from a variety of governments, churches and private citizens. Most of the Bonus Army, as they became known, camped in a Hooverville on the Anacostia Flats, a swampy, muddy area across the Anacostia River from the federal core of Washington.

On June 16, 1932, the House passed the bonus bill to immediately give the vets their bonus money by a vote of 209-176, but on June 18, the Senate defeated the bill 62-18.

On June 16, 1932, the House passed the bonus bill to immediately give the vets their bonus money by a vote of 209-176, but on June 18, the Senate defeated the bill 62-18.

Many Americans were outraged. How could the army treat veterans of the Great War with such disrespect?

Many marchers remained at their campsites hoping President Hoover would act positively on their plea for assistance. That did not happen.

Rather, on July 28, 1932, Hoover had his Attorney General, William D. Mitchell, order police to remove the Bonus Army veterans from their camp. When Veterans rushed two policemen trapped on the second floor of a building, the cornered police drew their revolvers and shot two veterans, killing William Hushka and Eric Carlson. When told of the shootings, President Hoover then ordered the army to evict the Bonus Army from Washington.

In charge of breaking up the camp was Chief of Staff Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Six battle tanks supporting the operation were commanded by Maj. George S. Patton, formed in Pennsylvania Avenue. At the same time, thousands of civil service employees left work to line the street and watch.

In charge of breaking up the camp was Chief of Staff Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Six battle tanks supporting the operation were commanded by Maj. George S. Patton, formed in Pennsylvania Avenue. At the same time, thousands of civil service employees left work to line the street and watch.

The Bonus marchers believing the troops were marching in their honor, cheered the troops until Patton allegedly ordered the cavalry to charge them- an action which prompted the spectators to yell, "Shame! Shame!" Soldiers with fixed bayonets followed, hurling tear gas into the crowd.

Army troops stormed several buildings that the veterans were occupying as well as their main camp, setting tents on fire and forcing an evacuation. When it was over, in addition to the two  veterans that had been killed by police, several babies died from tear gas, and scores of veterans and Washington police had been injured in various confrontations. Nearby hospitals were overwhelmed with casualties.

veterans that had been killed by police, several babies died from tear gas, and scores of veterans and Washington police had been injured in various confrontations. Nearby hospitals were overwhelmed with casualties.

The incident marked one of the greatest periods of unrest our nation's capital had ever know. General Douglas MacArthur and President Herbert Hoover suffered irreversible damage to their reputations after the affair.

It was especially disastrous for Hoover's chances at re-election; he lost the 1932 election in a landslide to Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Perhaps as atonement for their shabby treatment of the veterans and pressure from the public, Congress passed the Adjusted Compensation Payment Act of 1936, replacing the 1924 Act's service certificates with bonds issued by the Treasury Department that could be cashed at any time.

Congress was given another chance of redemption near the end of World War II. Again, it failed its duties and came close to stopping a bill designed to provide returning veterans with money

Congress was given another chance of redemption near the end of World War II. Again, it failed its duties and came close to stopping a bill designed to provide returning veterans with money  for education, unemployment, and home loans. Those against the bill said it would encourage veterans not to seek work and that providing money for a college education was not necessary since college was for rich kids.

for education, unemployment, and home loans. Those against the bill said it would encourage veterans not to seek work and that providing money for a college education was not necessary since college was for rich kids.

In spite of their opposition, the bill passed by a single vote (Rep. John Gibson of Georgia was rushed in to cast the tie-breaking vote) and even before the war had ended, President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Servicemen's Readjustment Act, otherwise known as the GI Bill of Rights, on June 22, 1944.

The G.I. Bill prevented a repetition of the Bonus March of 1932.

Unlike the Bonus Bill, the GI Bill offered Word War II vets a raft of benefits that reshaped postwar America for decades to come. It established hospitals, made low-interest mortgages

Unlike the Bonus Bill, the GI Bill offered Word War II vets a raft of benefits that reshaped postwar America for decades to come. It established hospitals, made low-interest mortgages  available, and granted stipends covering tuition and expenses for veterans attending college or trade schools. From 1944 to 1949, nearly 9 million veterans received close to $4 billion from the bill's unemployment compensation program, which was actually less than 20 percent of the money set aside for unemployment. Instead, most returning servicemen quickly found jobs or pursued higher education. Many also took advantage of home loans.

available, and granted stipends covering tuition and expenses for veterans attending college or trade schools. From 1944 to 1949, nearly 9 million veterans received close to $4 billion from the bill's unemployment compensation program, which was actually less than 20 percent of the money set aside for unemployment. Instead, most returning servicemen quickly found jobs or pursued higher education. Many also took advantage of home loans.

The education and training provisions existed until 1956, while the Veterans Administration offered insured loans until 1962.

Those more visionary elected officials representing that small majority that help squeak through the enactment of the GI Bill knew it had far greater implications. For them, it was seen as a genuine attempt to thwart a looming social and economic crisis.  Some saw inaction as an invitation to another depression.

Some saw inaction as an invitation to another depression.

Recognizing the importance of the GI Bill years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Readjustment Benefits Act of 1966, which changed the nature of military service in America by extending benefits to veterans who served during times of war and peace.

One can only hope today's Congress and those in the near and distant future understand the value and importance of keeping the GI Bill in full force and sufficiently funded. To do less would be to dishonor our veterans and the many sacrifices they made and continue to make.