The Second World War opened a new chapter in the lives of Depression-weary Americans. As husbands and fathers, sons and brothers shipped out to fight in Europe and the Pacific, millions of women marched into factories, offices, and military bases to work in paying jobs and in roles traditionally reserved for men in peacetime. It was also a time that offered new professional opportunities for women journalists - a path to the rarest of assignments, war reporters.

|

Talented and determined, dozens of women fought for the right to cover the biggest story of their lives. By war's end, at least 127 American women managed to obtain official accreditation from the U.S. War Department as war correspondents. Rules imposed by the military, however, stated women journalists could not enter the actual combat zone but remain in the rear areas writing stories of soldiers healing their wounds in field hospitals or other pieces supporting the war effort.

In spite of U.S. military regulations that barred women to accompany fighting forces into combat, Clare Hollingworth, Martha Gellhorn, Lee Miller, Margaret Bourke-White, Marguerite Higgins, Dickey Chapelle, and many others found ways to get "where the action was." They displayed tenacity, bravery, and a fresh approach to reporting war that gave the world some of the most distinctive and daring chronicles of an epic period of history. They did it, not just because they were exceptional women, but because they were great journalists.

In early 1939, peace activist Clare Hollingworth arrived on the Polish-German border to aid Jews and other refugees fleeing from the Sudetenland, newly annexed by Nazi Germany. On a brief return to her native England, the 27-year-old Hollingworth - who once professed to "enjoy being in a war," was hired as a part-time correspondent in Katowice, Poland, for the London Daily Telegraph.

After just three days into her first job that August, the cub reporter landed one of the biggest journalistic scoops of the 20th century.

|

Wanting to get a sense of the rising tensions between the two nations, she decided to drive across the border into Nazi German. Without divulging the reason, she asked to borrow a diplomatic vehicle from her ex-lover, the British consul in Katowice, knowing the Union Jack flag on its hood would get her across the heavily restricted border. On her return trip to Poland, she drove by an enormous canvas designed to block anyone from looking down into a valley below. As she drove further, a gust of wind lifted a portion of a tarp. She looked through the opening and spotted "literally hundreds of tanks, armored cars, and field guns." Realizing Germany was about to invade Poland, she called the London Daily Telegraph correspondent in Warsaw, and he filed a front-page story published on Aug. 29, 1939, under the headline "1,000 tanks massed on the Polish border. Ten divisions reported ready for swift stroke." Three days later, she awoke to the sounds of German planes and Panzer tanks invading Poland. It was the start of World War II and the beginning of her five-decade career as a war reporter.

During the North African desert campaign, British commander Bernard Montgomery ("something of a women-hater," she later wrote) expelled Hollingworth from his press contingent, saying that women did not belong on the front lines. She then joined with American troops under Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower's command in Algiers. Embedded with Allied troops, the 5-foot-3 journalist dodged bullets and German patrols, slept in the open desert, and learned to parachute and pilot a plane.

|

Following World War II, she covered hostilities from Algeria's war of independence in the 1950s to the Vietnam War in the '60s where a sniper's bullet narrowly missed her head. "No battlefield was complete" without her, the British author and war correspondent Tom Pocock once remarked.

The BBC stated that although she was not the earliest woman war correspondent, "her depth of technical, tactical, and strategic insight set her apart." The New York Times described her as "the undisputed notable of war correspondents." She amassed considerable expertise in military technology and, after pilot training during the 1940s, was particularly knowledgeable about aircraft.

In 1962, Hollingworth won Woman Journalist of the Year for her reporting of the civil war in Algeria.

From 1981, Hollingworth lived in Hong Kong. She was a near-daily visitor to the Foreign Correspondents' Club, where she was an honorary goodwill ambassador. In 1990, she published her memoirs under the title 'Front Line.'

On January 10, 2017, Clare Hollingworth died in Hong Kong at the age of 105.

By the time the United States entered WWII in 1941, the tall, beautiful Martha Gellhorn had been reporting war for six years, including the Civil War in Spain, the Russian invasion of Finland, and the Japanese invasion of China.

Her career as a war reporter began shortly after meeting writer and war reporter, Ernest Hemingway, in a bar in Key West in 1936. On vacation with her family after the success of her book The Troubles I've Seen,' written for the Roosevelt Administration about the effects of the Depression on ordinary Americans, she met Hemingway who was still married to his second wife, Pauline. Intrigued by the famous author and flattered by his attentions, Gellhorn was eager to move on to the next phase of her life. They vowed to meet again in Spain.

|

In Spain, Gellhorn, and Hemingway, her future husband, reported on the fascist uprising against the Republican government. Gellhorn felt ill-equipped to be a war reporter for Collier's Weekly because she was not knowledgeable about artillery or battle maneuvers. As her biographer Caroline Moorehead describes it: "Hemingway said to her 'why aren't you writing about the war,' and she said 'I don't know about weapons and battles,' and he said 'write about what you do know and that is people'." Thus began Gellhorn's style of war reporting: the effects of war on ordinary people.

As the war in Europe raged, Gellhorn was unable to get official accreditation from U.S. War Department as a war correspondents. "It is necessary that I report on this war," she fumed in an angry letter to military authorities "I do not feel there is any need to beg as a favor for the right to serve as the eyes for millions of people in America who are desperately in need of seeing but cannot see for themselves."

She was writing from London in June 1944, where she and other women war correspondents gathered in anticipation of the Normandy landings on the French coast which, marked the start of a major offensive against Germany.

Like any major news event today, there was an extraordinary buzz among journalists waiting in the city, hanging out in hotels such as the elegant Dorchester in the heart of London.

And a group of U.S. women, gutsy and glamorous, was part of it; they were fighting their own battles on every front to overcome the ban on women going to the front lines in the Second World War.

"They were all watching each other, and there was a huge sense of competitiveness," wrote biographer Caroline Moorehead. "Even Martha, who was not very interested in scoops, was affected by this huge sense of excitement."

Gellhorn had her scoop - a remarkable one - when she smuggled herself onto a hospital ship to get to Normandy, locked herself in a toilet, and became the first woman to report on the invasion.

|

"When night came, the water ambulances were still churning into the beach, looking for the wounded. We waded ashore in the water to our waist," she wrote.

While on the Normandy beachhead, she wrote: "The stretcher-bearers that were part of the American personnel started on their long back-breaking job. By the end of that trip, their hands were covered in blisters, and they were practically hospital cases themselves. It will be hard to tell you of the wounded; there were so many of them. There was no time to talk, there was too much else to do.

"Cigarettes had to be lighted and held for those who couldn't use their hands. It seemed to take hours to pour hot coffee via the spout of a teapot into a mouth just showing through bandages."

This was a historic period, marking a turning point for women reporting from warzones. They reached front lines, sent dispatches from Normandy, entered newly liberated Paris, and later visited concentration camps across Europe. Gellhorn was also among the first journalists to report from Dachau concentration camp after it was liberated by Allied Troops.

Her work was fiercely uncompromising. For many, Gellhorn's dispatches set new standards for narrative frontline journalism. Her volume 'The Face of War' remains as strong an indictment as any penned by the Hemingways of the world.

This was a historic period, marking a turning point for women reporting from warzones. They reached front lines, sent dispatches from Normandy, entered newly liberated Paris, and later visited concentration camps across Europe.

The legacy of the Nazi atrocities continued to occupy her. She covered the trial of German war criminal Adolf Eichmann for the Atlantic Monthly. She went to Israel in 1967 to cover the Arab-Israeli War with an impassioned pro-Israel standpoint, explaining that she saw conflict through the prism of the Holocaust.

|

In 1966 Gellhorn traveled to Vietnam to write about the war for the London Guardian, which she found supremely disturbing and horrific, full of victims on both sides of the battles lines. Her dispatches openly protested the war. "People cannot survive our bombs," she wrote. "We are uprooting the people from the lovely land where they have lived for generations, and the uprooted are given not bread but stone. Is this an honorable way for a great nation to fight a war 8,000 miles from its safe homeland?" The South Vietnamese government banned her from returning there, sending her into a long depression.

In the 1980s, she continued to travel extensively, writing about the wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua and the U.S. invasion of Panama, and in the mid-1990s, she went to Brazil to write about street children there. She reported on virtually every major world conflict that took place during her 60-year career.

She is now considered one of the greatest war correspondents of the 20th century.

In her last years, Gellhorn was in frail health, nearly blind and suffering from ovarian cancer that had spread to her liver. On February 15, 1998, she committed suicide in London apparently by swallowing a cyanide capsule. She was 89.

|

One of Gellhorn's journalist contemporaries, Lee Miller, is remembered today as a woman equally at ease on both sides of the camera. She rose to fame as one of Vogue magazine's most beautiful fashion models in 1927 and subsequently evolved into one of its leading photojournalists of World War II. In this capacity, she documented the liberation of France, Belgium, and Luxembourg before accompanying the American advance into Germany. She was also America's first female war correspondent who unflinchingly photographed the horrors of German concentration camps Buchenwald and Dachau.

Her journey as a photographer began in 1929 when she traveled to Paris with the intention of apprenticing herself to the surrealist artist and photographer Man Ray. Although at first, he insisted that he did not take students, Miller soon became his model and collaborator, as well as his lover and muse.

After leaving Man Ray and Paris in 1932, she returned to New York and established a portrait and commercial photography studio with her brother Erik as her darkroom assistant.

In 1934, she abandoned her studio to marry Egyptian aristocrat and railroad tycoon Aziz Eloui Bey. Although she did not work as a professional photographer during this period, the photographs she took while living in Egypt with Eloui, including Portrait of Space, are regarded as some of her most striking surrealist images.

By 1937, Miller had grown bored with her life in Cairo and returned to Paris, where she met the British surrealist painter and curator Sir Roland Penrose, whom she later would marry.

|

At the outbreak of World War II, Miller was living in Hampstead in London with Penrose when the bombing of the city began. Ignoring pleas from friends and family to return to the U.S., Miller embarked on a new career in photojournalism as the official war photographer for Vogue, documenting the Blitz.

By December 1942, she was accredited as a war correspondent for Vogue, which was thrilled to have its own writer who could tell a story of women and war, and much more.

She photographed women playing many roles, including nurses, charity workers, and the WRENS (Women Royal Naval Services). But some of her most vivid reporting was, in St Malo, France in August 1944, where she had been told the fighting was over but wasn't.

"I sheltered in a Kraut dugout squatting under the ramparts. My heel ground into a dead detached hand, and I cursed the Germans for the sordid ugly destruction they had conjured up in the once beautiful town," she wrote in Vogue.

"I picked up the hand and threw it back the way I had come and ran back, bruising my feet and crashing into the unsteady piles of stone and slipping in the blood. Christ, it was awful."

|

During this time, she photographed dying children in a Vienna Hospital, peasant life in post-war Hungary, and finally, the execution of Prime Minister Laszlo Bardossy. She also teamed up with the American photographer David E. Scherman, a LIFE correspondent on many assignments. A photograph by Scherman of Miller in the bathtub of Adolf Hitler's apartment in Munich is one of the most iconic images from the Miller-Scherman partnership.

After the war, she continued to work for Vogue for a further two years, covering fashion and celebrities.

When she discovered she was pregnant by Penrose with her only son, Antony, she divorced Bey and, on May 3, 1947, married Penrose.

Miller died from cancer at Farley Farm House in Chiddingly, East Sussex, in 1977, aged 70. She was cremated, and her ashes were spread through her herb garden at Farley Farm House.

"Today, we would understand she was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder," Penrose said of his mother, who at one point in the war was under fire for 30 days. "She entered into a spiral of depression, which took her 20 years to claw her way up out of."

One of those equally determined colleagues was Life magazine's Margaret Bourke-White, the best-known American woman photographer of the day and the first female war correspondent and the first woman to be allowed to work in combat zones during World War II.

As the only foreign photojournalist in Moscow when the Germans invaded Russia, her pictures of flares and searchlights and anti-aircraft tracers streaking the night sky over the Kremlin were published around the world. She made them from her hotel balcony or the roof of the American embassy, flaunting a Soviet edict that anyone caught taking pictures would be shot.

|

Despite her fame and reputation, Bourke-White faced many difficulties. She was denied access to cover the Allied invasion of North Africa, the excuse being that it was too dangerous for a woman to fly there from England. She instead took a ship - the England-Africa bound British troopship SS Strathallan - which was promptly torpedoed in the Mediterranean. Carrying only her cameras into the lifeboat, Bourke-White then produced a riveting coverage on the dangers of wartime travel at sea that she recorded in an article, "Women in Lifeboats", in Life, February 22, 1943. She was disliked by Gen. Dwight D Eisenhower but was friendly with his chauffeur/secretary, Irishwoman Kay Summersby, with whom she shared the lifeboat.

In January 1943, she finally won permission to become the first woman ever to fly on an American air combat mission. And during the Italian campaign, admiring soldiers watched her drag her camera and tripod through sniper fire to exposed ridgetops and take panoramic shots of the fighting.

|

In the spring of 1945, she traveled throughout a collapsing Germany with Gen. George S. Patton. She arrived at Buchenwald, the notorious concentration camp, and later said, "Using a camera was almost a relief. It interposed a slight barrier between myself and the horror in front of me." After the war, she produced a book entitled, 'Dear Fatherland, Rest Quietly,' a project that helped her come to grips with the brutality she had witnessed during and after the war.

To many who got in the way of a Bourke-White photograph - and that included not just bureaucrats and functionaries but professional colleagues like assistants, reporters, and other photographers - she was regarded as imperious, calculating, and insensitive.

In 1953, Bourke-White developed her first symptoms of Parkinson's disease. She was forced to slow her career to fight encroaching paralysis. In 1959 and 1961, she underwent several operations to treat her condition, which effectively ended her tremors, but affected her speech. In 1971 she died at Stamford Hospital in Stamford, Connecticut, aged 67, from Parkinson's disease.

Marguerite Higgins covered World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, and in the process, advanced the cause of equal access for female war correspondents. She had a long career with the New York Herald Tribune and later, as a syndicated columnist for Newsday.

Eager to become a war correspondent, Higgins persuaded the management of the New York Herald Tribune to send her to Europe in 1944 after working for them for two years. After being stationed in London and Paris, she was reassigned to Germany in March 1945. She witnessed the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp in April 1945 and received a U.S. Army campaign ribbon for her assistance during the surrender by its S.S. guards. She later covered the Nuremberg war trials and the Soviet Union's blockade of Berlin.

|

In 1950, Higgins was named chief of the Tribune's Tokyo bureau. Shortly after her arrival in Japan, war broke out in Korea, she came to the country as one of the first reporters on the spot. On June 28, Higgins and three of her colleagues witnessed the Hangang Bridge bombing and were trapped on the north bank of Han River as a result. After crossing the river by raft and coming to the U.S. military headquarters in Suwon on the next day, she was quickly ordered out of the country by Gen. Walton Walker, who argued that women did not belong at the front and the military had no time to worry about making separate accommodations for them. Higgins made a personal appeal to Walker's superior officer, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who subsequently sent a telegram to the Herald-Tribune stating, "Ban on women correspondents in Korea has been lifted". Marguerite Higgins is held in the highest professional esteem by everyone.

This was a major breakthrough for all female war correspondents. As a result of her reporting from Korea, Higgins was the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for Foreign Correspondence awarded in 1951 for her coverage of the Korean War, which she shared with five male war correspondents.

She contributed along with other major journalistic and political figures to the Collier's magazine collaborative special issue Preview of the War We Do Not Want, with an article entitled "Women of Russia."

While on assignment in late 1965, Higgins contracted leishmaniosis, a disease that led to her death on January 3, 1966, aged 45, in Washington, D.C. She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery with her husband Lt. Gen. William Evans Hall, U.S. Air Force.

On the other side of the globe, covering the war in the Pacific, there worked one photographer many today consider the epitome of the woman combat reporter. "She was always where the action was."

Dickey Chapelle, a middle-aged freelance photographer, carried her own pack and dug her own trench was an American photojournalist known for her work as a war correspondent from World War II through the Vietnam War.

|

Despite her mediocre photographic credentials, during World War II Chapelle, managed to become a war correspondent photojournalist for National Geographic, and with one of her first assignments, was posted with the Marines during the battle of Iwo Jima. On that hellish volcanic island, one of the bloodiest battles of the Pacific war was raging. Fighting was so fierce that 27 Medals of Honor would be awarded, but Chapelle doggedly made her way to the front, exposing herself to enemy fire as she worked.

Then came Okinawa, an even bloodier affair, and as the Japanese launched waves of kamikaze attacks, Chapelle eluded restrictions placed specifically on her and again reached the combat zone. At one point, she was hundreds of yards in front of the line. Authorities decided to chase her down. When found weeks later, the tiny figure in helmet and filthy fatigues and shouldering a heavy pack looked indistinguishable from other Marines. And always, everywhere, the bathroom excuse: No facilities for women - permission denied. One enraged general barked at Chapelle that he didn't want one hundred thousand Marines pulling up their pants because she was around. But Dickey could outstare any general. She countered with an answer that spoke for all her female colleagues, wherever in this far-flung conflict, they tried to work. "That won't bother me one bit,"' she replied. "My object is to cover the war."

After the war, she traveled all around the world, often going to extraordinary lengths to cover a story in any war zone. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Chapelle was captured and jailed for over seven weeks. She later learned to jump with paratroopers, and usually traveled with troops.

|

During the Vietnam War in the 1960s and early 1970s, correspondents in unprecedented numbers were covering the war. For them, it was a combination of intellectual curiosity, professional longings to be at the center of a big story, and a simple lust for adventure drew women to the jungles of Southeast Asia, just as those same urges had long drawn men to the spectacle of war. With these much younger women reporters was Dickey Chapelle.

Her stories in the early 1960s extolled the American military advisors who were already fighting and dying in South Vietnam, and the Sea Swallows, the anti-communist militia led by Father Nguyen Lac Hoa.

Chapelle was killed in Vietnam on November 4, 1965, while on patrol with a Marine platoon during Operation Black Ferret, a search and destroy operation 16 km south of Chu Lai, Quang Ngai Province, I Corps.

The Lieutenant in front of her kicked a tripwire booby trap, consisting of a mortar shell with a hand grenade attached to the top of it. Chapelle was hit in the neck by a piece of shrapnel that severed her carotid artery; she died soon after.

Her last moments were captured in a photograph by Henri Huet. Her body was repatriated with an honor guard consisting of six Marines, and she was given full Marine burial. She became the first female war correspondent to be killed in Vietnam, as well as the first American female reporter to be killed in action.

|

In paying the ultimate price, she won the ultimate respect. Her remains returned to the United States accompanied by a Marine Corps honor guard. No less than the Commandant of the Marine Corps himself then wrote, "She was one of us, and we shall miss her." And the Women's Press Club declared her to be "the kind of reporter all women in journalism openly or secretly aspire to be. She was always where the action was."

Today women report from embedded positions wherever the action is, and no one is telling them, at least openly, that they don't belong. For that, they can thank the pioneers of World War II, those women who 75 years ago fought the truly difficult fight and won the really important battle, the right to wear with respect the words stitched over the uniform's left breast pocket, "War Correspondent."

On June 28, 2005, deep behind enemy lines east of Asadabad in the Hindu-Kush of Afghanistan, a very dedicated four-man Navy SEAL team was conducting a counter-insurgency mission at the unforgiving altitude of approximately  10,000 feet. Lt. Michael Murphy was the officer in charge of the SEAL team. The other three members were Gunner's Mate 2nd Class Danny Dietz, Sonar Technician 2nd Class Matthew Axelson and Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class Marcus Luttrell. Their assignment was to capture or kill high-value target Ahmad Shah - a terrorist leader of a Taliban guerrilla group known as the "Mountain Tigers" that had aligned with other militant groups close to the Pakistani border. The mission was in response to Shah's group killing over twenty U.S. Marines, as well as villagers and refugees who were aiding American forces.

10,000 feet. Lt. Michael Murphy was the officer in charge of the SEAL team. The other three members were Gunner's Mate 2nd Class Danny Dietz, Sonar Technician 2nd Class Matthew Axelson and Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class Marcus Luttrell. Their assignment was to capture or kill high-value target Ahmad Shah - a terrorist leader of a Taliban guerrilla group known as the "Mountain Tigers" that had aligned with other militant groups close to the Pakistani border. The mission was in response to Shah's group killing over twenty U.S. Marines, as well as villagers and refugees who were aiding American forces.

As the team carefully moved to where they hoped to find Shah, the SEALs were accidentally discovered by an elderly shepherd and two teenage goat herders. Knowing that if they release them, the herders will likely alert the Taliban to their presence, the team is split about whether to execute the herders or not. After a brief debate, Luttrell convinces the others that they will incite backlash if they kill the three herders. The team decides to release the herders and abort the mission, but before they can escape, they are discovered by Taliban forces.

A fierce firefight erupted between the four SEALs and a much larger enemy force of more than 50 anti-coalition militia. The enemy had the SEALs outnumbered. They also had terrain advantage. They launched a well-organized, three-sided attack on the SEALs. The firefight continued relentlessly as the overwhelming militia forced the team deeper into a ravine.

Trying to reach safety, the four men, now each wounded, began vaulting down the mountain's steep sides, making leaps of 20 to 30 feet. Approximately 45 minutes into the fight, pinned down by overwhelming forces, Dietz, the communications petty officer, sought open air to place a distress call back to the base. But before he could, he was shot in the hand, the blast shattering his thumb.

Despite their injuries, the SEALs continue a defensive retreat through the steep woods. Dietz begins to lose consciousness and shouts questions to Luttrell, unwittingly revealing the team's position to the Taliban. Murphy and Axelson jump off another ridge to flee from the Taliban fighters. Luttrell tries to carry Dietz down the mountain, but Dietz is shot in the shoulder; the impact forces Luttrell to lose his grip and fall forward off the cliff. A dying Dietz remains at the top of the cliff and is killed by the Taliban insurgents. Murphy decides to try climbing back up the cliff to get a phone signal in order to call in support forces via satellite phone. Axelson and Luttrell shoot at the Taliban fighters to provide Murphy with cover.

Despite his severe wounds and continued enemy fire, he finally reached higher ground and alerted the SOF Quick Reaction Force at Bagram Air Base and requested immediate support for his team. He calmly provided his unit's location and the approximate size of the enemy force. At that point, he was shot in the back, causing him to drop the transmitter. Murphy picked it back up, completed the call, and continued firing at the enemy who were closing in. Severely wounded, he returned to his cover position with Axelson and Luttrell and continued the battle. By the end of the two-hour firefight that careened through the hills and over cliffs, an estimated 35 Taliban were also dead. So too was Murphy.

Despite his severe wounds and continued enemy fire, he finally reached higher ground and alerted the SOF Quick Reaction Force at Bagram Air Base and requested immediate support for his team. He calmly provided his unit's location and the approximate size of the enemy force. At that point, he was shot in the back, causing him to drop the transmitter. Murphy picked it back up, completed the call, and continued firing at the enemy who were closing in. Severely wounded, he returned to his cover position with Axelson and Luttrell and continued the battle. By the end of the two-hour firefight that careened through the hills and over cliffs, an estimated 35 Taliban were also dead. So too was Murphy.

|

In response to Murphy's distress call, two MH-47 Chinook helicopters - one loaded with eight Navy SEALs and eight Army Night Stalkers - were sent is as part of an extraction mission to pull out the four embattled SEALs. The MH-47s were escorted by heavily-armored, Army attack helicopters. Entering a hot combat zone, attack helicopters are used initially to neutralize the enemy and make it safer for the lightly-armored, personnel-transport helicopter to insert.

|

The heavyweight of the attack helicopters slowed the formation's advance prompting the MH-47s to outrun their armored escort. They knew the tremendous risk going into an active enemy area in daylight, without their attack support, and without the cover of night. The risk would, of course, be minimized if they put the helicopter down in a safe zone. But knowing that their warrior brothers were shot, surrounded, and severely wounded, the rescue team opted to directly enter the oncoming battle in hopes of landing on brutally hazardous terrain. During an attempt to insert the arriving forces, the Taliban insurgents shoot down one of the helicopters, killing eight Navy SEALs and eight Special Operations aviators who were on board. The second helicopter was forced to turn back.

|

After witnessing the attack, Luttrell and a badly injured Axelson are left behind. Axelson attempts to find cover but is killed when he leaves his hiding spot to attack several approaching insurgents. Luttrell was blasted over a ridge by a rocket-propelled grenade and was knocked unconscious. Regaining consciousness sometime later, Luttrell managed to escape - badly injured - and slowly crawl away down the side of a cliff. Dehydrated, with a bullet wound to one leg, shrapnel embedded in both legs, three vertebrae cracked; the situation for Luttrell was grim. Rescue helicopters were sent in, but he was too weak and injured to make contact. Traveling seven miles on foot, he evaded the enemy for nearly a day.

When he is finally discovered by the Taliban, one of the insurgents fired a rocket-propelled grenade, and its impact caused him to land at the bottom of a rock crevice where he was able to hide from the Taliban fighters.

Luttrell stumbled upon a small body of water and submerged himself, only to find upon surfacing that a local Pashtun villager, Mohammad Gulab, has discovered his location. Gulab took Luttrell into his care, returning to his village, where he attempts to hide Luttrell in his home. The Taliban came to the village several times, demanding that Luttrell be turned over to them.  The villagers refused. Gulab then sent a villager to a Marine outpost with a note from Luttrell. The Taliban fighters returned to the village to capture and kill Luttrell, but Gulab and the villagers intervene, threatening to kill the fighters if they harm Luttrell. The fighters leave, but later return to punish the villagers for protecting Luttrell. Gulab and his fellow militia are able to fend off several fighters during the ensuing attack. U.S. commandos, arriving via helicopters on July 3, 2005, shattered the advancing Taliban and, in the process, kill the bulk of the insurgents with concentrated weaponry fire. The American forces successfully evacuate Luttrell back to base.

The villagers refused. Gulab then sent a villager to a Marine outpost with a note from Luttrell. The Taliban fighters returned to the village to capture and kill Luttrell, but Gulab and the villagers intervene, threatening to kill the fighters if they harm Luttrell. The fighters leave, but later return to punish the villagers for protecting Luttrell. Gulab and his fellow militia are able to fend off several fighters during the ensuing attack. U.S. commandos, arriving via helicopters on July 3, 2005, shattered the advancing Taliban and, in the process, kill the bulk of the insurgents with concentrated weaponry fire. The American forces successfully evacuate Luttrell back to base.

|

By his undaunted courage, intrepid fighting spirit and inspirational devotion to his men in the face of certain death, Lt. Murphy was able to relay the position of his unit, an act that ultimately led to the rescue of Luttrell and the recovery of the remains of the Axelson and Dietz. On July 4, 2005, Murphy's remains were found by a group of American soldiers during a combat search and rescue operation and returned to the United States. Nine days later, on July 13, Murphy was buried with full military honors at Calverton National Cemetery, Calverton, New York, Section 67, Grave No. 3710, less than 20 miles from his childhood home.

This was the worst single-day U.S. Forces death toll since Operation Enduring Freedom began. It was the single largest loss of life for Naval Special Warfare (NSW) since World War II.

Subsequent to the SEAL ambush and MH-47 shoot down, Shah and his men escaped to Pakistan, where they produced a video from footage they shot of the ambush that included weapons and implements captured from the SEALs. In late July 2005, Shah and his men returned to the Kunar Province and began attacking the United States, Coalition, and Government of Afghanistan entities.

Shah was killed during a shootout with Pakistani police in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, in April 2008, after failing to stop at a security checkpoint whilst transporting a kidnapped trader. An official from Kunar Province stated that Shah had been the "most wanted terrorist" in Kunar province.

|

On September 14, 2006, Dietz and Axelson were posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for "undaunted courage" and heroism. Luttrell was also awarded the Navy Cross in a ceremony at the White House. In 2007, Murphy was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions during the battle. The eight SEALs who died in their heroic attempt to rescue them were all awarded the Bronze Star.

Murphy was born on May 7, 1976, in Smithtown, New York, to Irish American parents Maureen and Daniel Murphy, a former assistant Suffolk County district attorney and Vietnam veteran. He was raised in Patchogue. He attended Saxton Middle School, where he played youth soccer and pee-wee football, with his father as a coach. In high school, he continued playing sports and took a summer job as a lifeguard at the Brookhaven town beach in Lake Ronkonkoma. He returned to the job every summer throughout his college years.

|

Murphy was known to his friends as "Murph," and he was known as "The Protector" in his high school years. In 8th grade, he protected a child with special needs who was being shoved into a locker by a group of boys; this was the only time the principal of the school had called his parents, they couldn't have been prouder. He also protected a homeless man who was being attacked while collecting cans. He chased away the attackers and helped the man pick up his cans.

In 1994, Murphy graduated from Patchogue-Medford High School and left home to attend The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State). He graduated from Penn State in 1998 with degrees in both political science and psychology. He was also accepted to several law schools but decided to attend SEAL mentoring sessions at the United States Merchant Marine Academy. In September 2000, he accepted an appointment to the U.S. Navy's Officer Candidate School in Pensacola, Florida. On December 13 of that year, he was commissioned as an Ensign in the Navy and began Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL (BUD/S) training in Coronado, California, in January 2001, eventually graduating with Class 236.

|

Upon graduation from BUD/S, he attended the U.S. Army Airborne School, SEAL Qualification Training and SEAL Delivery Vehicle (SDV) School. Murphy earned his SEAL Trident and checked on board SDV Team ONE (SDVT-1) in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in July 2002. In October 2002, he deployed with Foxtrot Platoon to Jordan as the Liaison Officer for Exercise Early Victor. Following his tour with SDVT-1, Murphy was assigned to Special Operations Command Central (SOCCENT) in Florida and deployed to Qatar in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan.

One of Murphy's SEAL BUD/S instructors wrote, "I've heard from the one who survived, details about your final moments, and I want to say that you are an inspiration, a hardcore warrior through and through, exactly what every Team guy aspires to be like."

A BUD/S classmate inspired by Michael's toughness and determination wrote, "I remember you with your stress fractures post-Hell-Week and limping around with your iron will. Those thoughts will never leave my mind and further commit myself to our country's undying cause of freedom."

And a personal friend recalled, "We always knew he was a tough son of a bitch, but he was so nice." At the end of his radio transmission for help, despite his severe wounds and dire situation, Murphy ' ever the officer and gentleman ' said, "Thank you."

Photos of the real-life Marcus Luttrell, Mohammad Gulab, and the fallen service members who died during the mission are shown during a four-minute montage, and an epilogue reveals that the Pashtun villagers agreed to help Luttrell as part of a traditional code of honor known as the Pashtunwali.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1gYyurUdy7Y

Lone Survivor Book and Movie

|

"Lone Survivor" is a 2013 American war film based on the 2007 non-fiction book of the same name by Marcus Luttrell with Patrick Robinson. Written and directed by Peter Berg, the film stars Mark Wahlberg, Taylor Kitsch, Emile Hirsch, Ben Foster, and Eric Bana. Set during the war in Afghanistan, Lone Survivor dramatizes the unsuccessful United States Navy SEALs counter-insurgent mission Operation Red Wings, during which a four-man SEAL reconnaissance and surveillance team were tasked to track down and kill Taliban leader Ahmad Shah.

Berg first learned of the book Lone Survivor in 2007, while he was filming Hancock (2008). He arranged several meetings with Luttrell to discuss adapting the book to film. Universal Pictures secured the film rights in August 2007 after bidding against other major film studios. In re-enacting the events of Operation Red Wings, Berg drew much of his screenplay from Luttrell's eyewitness accounts in the book, as well as autopsy and incident reports related to the mission. After directing Battleship (2012) for Universal, Berg returned to work on Lone Survivor. Principal photography began in October 2012 and concluded in November after 42 days; filming took place on location in New Mexico, using digital cinematography. Luttrell and several other Navy SEAL veterans acted as technical advisors, while multiple branches of the United States Armed Forces aided the film's production.

Lone Survivor opened in limited release in the United States on December 25, 2013, before opening across North America on January 10, 2014, to strong financial success and a generally positive critical response. Most critics praised Berg's direction, as well as the acting, story, visuals and battle sequences. Other critics, however, derided the film for focusing more on its action scenes than on characterization. Lone Survivor grossed over $154 million in box-office revenue worldwide - of which $125 million was from North America. The film received two Academy Award nominations for Best Sound Editing and Best Sound Mixing.

Battle Scenes from Movie

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QJwdXqGBEPQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QHpVb4L6izI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1xxa5eS31Hk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VuIINk0IftU

From July 1 to July 3, 1863, the invading forces of Gen. Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army clashed with the Army of the Potomac under its newly appointed leader, General George G. Meade at Gettysburg, some 35 miles southwest of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Casualties were high on both sides: Out of roughly 170,000 Union and Confederate soldiers, there were 23,000 Union and 28,000 Confederate casualties; more than one-quarter of the Union army's effective forces and more than a third of Lee's army were killed, wounded or missing.

After three days of battle, Lee retreated towards Virginia on the night of July 4. It was not only a crushing defeat for the Confederacy, but the battle also proved to be the turning point of the war: Gen. Robert E. Lee's defeat and retreat from Gettysburg marked the last Confederate invasion of Northern territory, and the beginning of the Southern army's ultimate decline.

After three days of battle, Lee retreated towards Virginia on the night of July 4. It was not only a crushing defeat for the Confederacy, but the battle also proved to be the turning point of the war: Gen. Robert E. Lee's defeat and retreat from Gettysburg marked the last Confederate invasion of Northern territory, and the beginning of the Southern army's ultimate decline.

As had become customary following previous mass-casualty battles, thousands of Union soldiers killed at Gettysburg were quickly buried, many in poorly marked graves. In the months that followed, however, local attorney David Wills spearheaded efforts to create a national cemetery at Gettysburg. Wills and the Gettysburg Cemetery Commission originally set October 23, 1863, as the date for the cemetery's dedication, but delayed it to mid-November after their choice for speaker, Edward Everett, said he needed more time to prepare. Everett, the former president of Harvard College, former U.S. senator and former secretary of state, was at the time one of the country's leading orators.

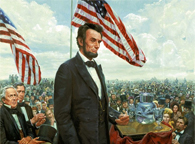

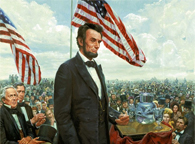

Almost as an afterthought, Wills also sent a letter to President Abraham Lincoln - just two weeks before the ceremony - requesting "a few appropriate remarks" to consecrate the grounds at the official dedication ceremony for the National Cemetery of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania; remarks which became famously known world-wide as the Gettysburg Address.

When he received the invitation to make the remarks at Gettysburg, Lincoln saw an opportunity to make a broad statement to the American people on the enormous significance of the war, and he prepared carefully. Though long-running popular legend holds that he wrote the speech on the train while traveling to Pennsylvania, he probably wrote about half of it before leaving the White House on November 18th and completed writing and revising it that night, after talking with Secretary of State William H. Seward, who accompanied him to Gettysburg.

|

On the morning of November 19, Everett delivered his two-hour oration (from memory) on the Battle of Gettysburg and its significance, and the orchestra played a hymn composed for the occasion by B.B. French. Lincoln then rose to the podium and addressed the crowd of some 15,000 people. He spoke for less than two minutes, and the entire speech was only 273 words long. Beginning by invoking the image of the founding fathers and the new nation, Lincoln eloquently expressed his redefined belief that the Civil War was not just a fight to save the Union, but a struggle for freedom and equality for all, an idea Lincoln had not championed in the years leading up to the war.

This was his stirring conclusion: "The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us - that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion - that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain - that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom - and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

|

The essential themes and even some of the language of the Gettysburg Address were not new; Lincoln himself, in his July 1861 message to Congress, had referred to the United States as "a democracy - a government of the people, by the same people." The radical aspect of the speech, however, began with Lincoln's assertion that the Declaration of Independence - and not the Constitution - was the true expression of the founding fathers' intentions for their new nation. At that time, many white slave owners had declared themselves to be "true" Americans, pointing to the fact that the Constitution did not prohibit slavery; according to Lincoln, the nation formed in 1776 was "dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal." In an interpretation that was radical at the time - but is now taken for granted - Lincoln's historic address redefined the Civil War as a struggle not just for the Union, but also for the principle of human equality.

On the day following the dedication ceremony, newspapers all over the country reprinted Lincoln's speech along with Everett's. Opinion was generally divided along political lines, with Republican journalists praising the speech as a heartfelt, classic piece of oratory and Democratic ones deriding it as inadequate and inappropriate for the momentous occasion. Nevertheless, the "little speech," as he later called it, is thought by many today to be the most eloquent articulation of the democratic vision ever written.

|

Some prescient observers sensed the power of Lincoln's achievement immediately. Everett was among them. The next day, he wrote to Lincoln, requesting a copy of the speech and covering it with praise: "Permit me also to express my great admiration of the thoughts expressed by you, with such eloquent simplicity & appropriateness, at the consecration of the cemetery. I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes." Lincoln replied gracefully, "In our respective parts yesterday, you could not have been excused to make a short address, nor I a long one. I am pleased to know that, in your judgment, the little I did say was not entirely a failure."

Lincoln's short speech also became a touchstone in American history, marking not only a turning point in the Civil War but also a reframing of that war as a struggle for human rights. More than tariffs, taxes, states' rights, or any of the numerous other political differences dividing North and South, the issue of slavery has come to dominate how history remembers the conflict - thanks in large part to Lincoln's speech. He successfully redefined the war as a fight to uphold the principles upon which the nation was founded, at the same time delivering one of the most beloved and best-remembered speeches in history.

After Lincoln's assassination in April 1865, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts wrote of the address, "That speech, uttered at the field of Gettysburg, and now sanctified by the martyrdom of its author, is a monumental act. In the modesty of his nature, he said 'the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here; but it can never forget what they did here.' He was mistaken. The world at once noted what he said, and will never cease to remember it."

In spite of what is widely considered one of the greatest speeches in American history, there are still a few points about the speech that are misunderstood even today.

1. Lincoln wrote every word of the Gettysburg Address.

While subsequent presidents have all enjoyed significant assistance from speechwriters in crafting their messages, President Lincoln took a more hands-on approach and is one of the few presidents in U.S. history to have written the entirety of his speeches and remarks.

2. Lincoln was not the main attraction at Gettysburg that day.

President Lincoln was invited to make a few remarks at the ceremony consecrating a new cemetery for Union soldiers, but he was not the keynote speaker. That honor went to Edward Everett, a leading academic and popular orator at the time. Everett spoke before the president, delivering a 13,607-word, 2-hour-long speech.

3. Lincoln's speech was just 10 sentences long.

|

In contrast to Everett's hours-long address, Lincoln spoke for just a few minutes. A popular myth tells of President Lincoln hastily jotting down his 273-word speech on the back of an envelope during the train ride from Washington to Gettysburg. In truth, Lincoln put a great deal of planning into his remarks. He began writing the speech the night before he left and completed it after his arrival in Pennsylvania.

4. The exact wording of Lincoln's remarks, as delivered, cannot be historically verified.

Modern speeches are often distributed electronically to news outlets as they are delivered - if not before. In 1863, journalists had to transcribe the text as it was spoken, leading to conflicting reports as to what President Lincoln said and how he said it. Adding to the confusion, Lincoln himself penned five different versions of the text for his personal secretaries and friends.

5. The Gettysburg Address does not explicitly discuss details of the war.

|

One reason for the enduring power of the Gettysburg Address is its timeless appeal. Rather than linking the speech to details of the war, Lincoln instead invoked universal ideals like devotion, democracy, human equality, and the importance of honoring the sacrifice of those who died for their country. He did not once explicitly mention the Union, the Confederacy, slavery, the Emancipation Proclamation, or even Gettysburg itself. He merely acknowledged the state of civil war and the battlefield losses and commemoration, before entering into the main theme of the speech, which was the need to continue the fight for freedom, which was the cause so gravely elevated by the battle's casualties.

6. The speech was not the first appearance of the phrase "of the people, by the people, and for the people."

While Lincoln is often credited with creating the phrase "government of the people, by the people, for the people," it is actually centuries older than America. The earliest usage can be found in the introduction to an English translation of the Bible by John Wycliffe in 1384 ("This Bible is for the Government of the People, by the People, and for the People.") The phrase also turns up in the 1850s in a book of sermons by abolitionist preacher Theodore Parker, a book which Lincoln received as a gift in the first months of the Civil War, and which was likely his source of inspiration for the wording of the now-legendary phrase.

7. The Gettysburg Address argues that the Declaration of Independence is more important than the Constitution.

|

Thomas Jefferson himself attempted to condemn slavery in the first draft of the Declaration of Independence but was thwarted by the opposition of southern slave states. However, he was still able to include in it the declaration of the equality of all men. But when the Constitution itself was written, southern states prevented the inclusion of the issue of equality.

And so, in the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln focused on that revolutionary ideal set forth "four score and seven years ago" in the Declaration of Independence by the anti-slavery efforts of founders Thomas Jefferson, Ben Franklin, and Alexander Hamilton, among others, that so eloquently stated in our founding document that "all men are created equal." Whereas slaveholders at the time argued that they had a constitutional right to own slaves, Lincoln called on America to welcome a "new birth of freedom," implying that the U.S. Constitution must change to embrace equal rights for all.

8. The response from those in attendance was overwhelmingly positive.

According to reports, the audience interrupted Lincoln five times to applaud his speech (though they offered only mildly polite applause at the conclusion of his remarks). Even with those five interruptions, Lincoln still managed to deliver his entire address in approximately 2-3 minutes.

9. The press response to Lincoln's speech was divided along partisan lines.

|

While the speech is hailed today as one of the greatest in history, contemporary responses were split with pro- and anti-Lincoln publications divided along party lines. The Democratic-leaning Chicago Tribune, for instance, called the speech "dish watery."

10. There is only one known photograph of President Lincoln at the ceremony.

Lincoln was captured in a photo of the crowd at the ceremony, with his head visible in the mass of people. Historians speculate that the brevity of Lincoln's remarks prevented photographers from setting up their complicated equipment in time to catch the president while still on stage. The photograph was taken by 18-year-old David Bachrach, who would later become notable as the uncle of writer Gertrude Stein.

The Gettysburg Address

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that this nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

|

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us - that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion - that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain - that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom - and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

*********************************

The rest, as they say, is history. With time, and frequent reprinting's, it became obvious that Lincoln had created a lapidary masterpiece, whose brevity was not the least of its merits. He succeeded in giving meaning to the terrible sacrifice, and in repurposing the United States. He elevated democracy and equality as fundamental goals of the government. And he changed the way we talk. His 273 words were short - mostly one- and two-syllable words, derived from Anglo-Saxon and Norman roots, the way that Americans actually spoke. Notably absent were flowery Greek and Latin phrases.

In 1868, many Lakota leaders of the Sioux nation agreed to a treaty, known as the Fort Laramie Treaty that created a large reservation for them in the western half of present-day South Dakota. They agreed to give up their nomadic life, which often brought them into conflict with other tribes in the region, with settlers, and with railroad surveyors, in exchange for a more stationary life relying on government-supplied subsidies. However, some Lakota leaders such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse rejected the reservation system. Likewise, many roving bands of hunters and warriors did not sign the 1868 treaty and consequently felt no obligation to conform to its restrictions or to limit their hunting to the unseeded hunting land assigned by the treaty. Their sporadic forays off the designated lands continually brought them into conflict with settlers and enemy tribes outside the treaty boundaries.

with other tribes in the region, with settlers, and with railroad surveyors, in exchange for a more stationary life relying on government-supplied subsidies. However, some Lakota leaders such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse rejected the reservation system. Likewise, many roving bands of hunters and warriors did not sign the 1868 treaty and consequently felt no obligation to conform to its restrictions or to limit their hunting to the unseeded hunting land assigned by the treaty. Their sporadic forays off the designated lands continually brought them into conflict with settlers and enemy tribes outside the treaty boundaries.

In 1874, the tension between the U.S. and the Lakota escalated when U.S. Army troops were ordered to explore the Black Hills inside the boundary of the Great Sioux Reservation. Their duties were to map the area, locate a suitable site for a future military post, and to make note of the natural resources. During the expedition, professional geologists discovered deposits of gold. Word of the discovery of mineral wealth created a gold rush of miners and entrepreneurs to the Black Hills in direct violation of the treaty of 1868. The U.S. negotiated with the Lakota to purchase the Black Hills, but the offered price was rejected. The climax came in the winter of 1875 when the Commissioner of Indian Affairs issued an ultimatum requiring all Sioux to report to the reservation by January 31, 1876. The deadline came with virtually no response from the natives, and matters were handed to the military, leading to the Great Sioux War of 1876.

|

Gen. Philip Sheridan, controversial Civil War general (for engineering the scorched earth strategy in the Shenandoah Valley that was instrumental in demoralizing and defeating the Confederacy), and commander of the Military Division of the Missouri, devised a strategy that committed several thousand troops to locate and attack the "renegade" Plains tribes of Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne - who were now considered "hostile" - and force their return to the Great Sioux Reservation. The campaign was set into motion in March 1876, when the Montana column, a 450-man force of combined cavalry and infantry commanded by Col. John Gibbon, marched out of Fort Ellis near Bozeman Montana. In the middle of May, a second force of 879 men commanded by Gen. Alfred Terry marched from Fort Abraham Lincoln, Bismarck, Dakota Territory, with a command comprised mostly of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer's 7th Cavalry. During the last week of May, a third force of about 1,000 cavalry and infantry commanded by Gen. George Crook was launched from Fort Fetterman in central Wyoming.

It was expected that any one of these three forces would be able to deal with the 800-1,500 warriors they were likely to encounter. The three commands of Gibbon, Terry, and Crook were not expected to launch a coordinated attack on a specific Indian village at a known location. Inadequate, slow, and often unpredictable communications hampered any real coordination of the Army's expeditionary forces. Furthermore, the nomadic hunting lifestyle of the Sioux and their Cheyenne allies had them constantly on the move. No officer or scout could be certain how long a village might remain stationary, or which direction the tribe might choose to go in search of food, water, and grazing areas for their horses.

|

The tribes, mostly Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho, came together in the region of the Powder, Rosebud, Bighorn, and Yellowstone rivers because it was a well-watered and productive hunting ground. But near the end of each spring, they also gathered there in large numbers for their annual Sun Dance ceremony. During their 1876 ceremony, which occurred around June 5 near present-day Lame Deer, Montana, just two weeks prior to their fateful meeting with Custer, Sitting Bull received a vision of soldiers falling upside down into his village. He prophesied there soon would be a great victory for his people.

On June 22, Gen. Terry decided to detach Custer and his 7th Cavalry to make a wide flanking march and approach the Indians from the east and south. Custer was to act as the hammer and prevent the Lakota and their Cheyenne allies from slipping away and scattering, a common fear expressed by government and military authorities. Terry and Col. Gibbon, with infantry and cavalry, would approach from the north to act as a blocking force or anvil in support of Custer's far-ranging movements toward the headwaters of the Tongue and Little Bighorn Rivers. The Indians, who were thought to be camped somewhere along the Little Bighorn River, "would be so completely enclosed as to make their escape virtually impossible." This grievous underestimation of the native forces led to what we now know as Custer's Last Stand, or the Battle of the Little Bighorn, otherwise known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, so-named for the "greasy" appearance of the grass in the waters near the battle site.

|

On the evening of June 24, Custer established a night camp twenty-five miles east of where the fateful battle would take place on June 25-26. The Crow and Arikara scouts were sent ahead, seeking actionable intelligence about the direction and location of the gathered Lakota and Cheyenne. The returning scouts reported that the trial indicated that the village had turned west toward the Little Bighorn River and was encamped about twenty-five miles west of the June 24 camp. Custer ordered a night march that followed the route that the village took as it crossed to the Little Bighorn River valley.

Early on the morning of June 25, the 7th Cavalry Regiment was positioned near the Wolf Mountains about 12-15 miles distant from the Lakota/Cheyenne encampment along the Little Bighorn River. The encampment, estimated to number about 8,000 with a warrior force of 1,500-1,800 men, was rife with rumors about soldiers on the other side of the Wolf Mountains, yet few were concerned. In the words of Low Dog, an Oglala Sioux, "I did not think anyone would come and attack us as strong as we were."

Custer's initial plan had been to conceal his regiment in the Wolf Mountains through June 25th, which would allow his Crow and Arikara scouts time to locate the Sioux and Cheyenne village. Custer then planned to make a night march, and launch an attack at dawn on June 26; however, the scouts reported the regiment's presence had been detected by Lakota or Cheyenne warriors. Custer, judging the element of surprise to have been lost, feared the inhabitants would attack or scatter into the rugged landscape and cause the Army's campaign to fail. Custer ordered an immediate advance to engage the village and its warrior force. His orders were to locate the Sioux encampment in the Big Horn Mountains of Montana and trap them until reinforcements arrived.

At the Wolf Mountain location, Custer ordered a division of the regiment into four segments: the pack train with ammunition and supplies, a three company force (125) commanded by Capt. Frederick Benteen, a three company force (140) commanded by Maj. Marcus Reno and a five company force (210) commanded by Custer. Benteen was ordered to march southwest, on a left oblique, with the objective of locating any Indians, "pitch into anything" he found, and send word to Custer. Custer and Reno's advance placed them in proximity to the village, but still out of view. When it was reported that the village was scattering, Custer ordered Reno to lead his 140 man battalion, plus the Arikara scouts, and to "pitch into what was ahead" with the assurance that he would "be supported by the whole outfit."

|

The Lakota and Cheyenne village lay in the broad river valley bottom, just west of the Little Bighorn River. As instructed by his commanding officer, Reno crossed the river about two miles south of the village and began advancing downstream toward its southern end. Though initially surprised, the warriors quickly rushed to fend off Reno's assault. Reno halted his command, dismounted his troops, and formed them into a skirmish line, which began firing at the warriors who were advancing from the village. Mounted warriors pressed their attack against Reno's skirmish line and soon endangered his left flank. Reno withdrew to a stand of timber beside the river, which offered better protection. Eventually, Reno ordered a second retreat, this time to the bluffs east of the river. The Sioux and Cheyenne, likening the pursuit of retreating troops to a buffalo hunt, rode down the troopers. Soldiers at the rear of Reno's fleeing command incurred heavy casualties as warriors galloped alongside the fleeing troops and shot them at close range, or pulled them out of their saddles onto the ground.

Reno's now shattered command crossed back over the Little Bighorn River and struggled up steep bluffs to regroup atop high ground to the east of the valley fight. Benteen had found no evidence of Indians or their movement to the south and had returned to the main column. He arrived on the bluffs in time to meet Reno's demoralized survivors. A messenger from Custer previously had delivered a written communication to Benteen that stated, "Come on. Big Village. Be Quick. Bring Packs. P.S. Bring Packs." An effort was made to locate Custer after heavy gunfire was heard downstream. Led by Capt. Weir's D Company, troops moved north in an attempt to establish communication with Custer.

|

Assembling on a high promontory (Weir Point) a mile and a half north of Reno's position, the troops could see clouds of dust and gun smoke covering the battlefield. Large numbers of warriors approaching from that direction forced the cavalry to withdraw to Reno Hill where the Indians held them under siege from the afternoon of June 25, until dusk on June 26. On the evening of June 26, the entire village began to move to the south.

The next day the combined forces of Terry and Gibbon arrived in the valley bottom where the village had been encamped. The badly battered and defeated remnant of the 7th Cavalry was now relieved. Scouting parties, advancing ahead of Gen. Terry's command, discovered the dead, naked, and mutilated bodies of Custer's command on the ridges east of the river. Several members of George Armstrong Custer's family were also killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, including two of his brothers, his brother-in-law, and a nephew.

|

Exactly what happened to Custer's command never will be fully known. From Indian accounts, archaeological finds, and positions of bodies, historians can piece together the Custer portion of the battle, although many answers remain elusive.

It is known that, after ordering Reno to charge the village, Custer rode northward along the bluffs until he reached a broad coulee known as Medicine Tail Coulee, a natural route leading down to the river and the village. Archaeological finds indicate some skirmishing occurred at Medicine Tail ford. For reasons not fully understood, the troops fell back and assembled on Calhoun Hill, a terrain feature on the ridges. The warriors, after forcing Reno to retreat, now began to converge on Custer's maneuvering command as it forged north along what, today, is called Custer or Battle Ridge.

|

Dismounting at the southern end of the ridge, companies C and L appear to have put up stiff resistance before being overwhelmed. Company I perished on the east side of the ridge in a large group, the survivors rushing toward the hill at the northwest end of the long ridge. Company E may have attempted to drive warriors from the deep ravines on the west side of the ridge or attempted to make their own last stand there, before being consumed in fire and smoke deep in the ravines. Company F may have tried to fire at warriors on the flats below the area now known as a National Cemetery before being driven to the Last Stand Site.

About 40 to 50 men of the original 210 were cornered on the hill where the monument now stands. Hundreds of Lakota and Cheyenne warriors surrounded them. Toward the end of the fight, soldiers, some on foot, others on horseback, broke out in a desperate attempt to get away. All were pulled down and killed in a matter of minutes. The warriors quickly rushed to the top of the hill, cutting, clubbing, and stabbing the last of the wounded. Superior numbers and overwhelming firepower brought the Custer portion of the Battle of the Little Bighorn to a close.

The battle was a momentary victory for the Sioux and Cheyenne. The total U.S. casualty count included 268 dead and 55 severely wounded (six of whom died later from their injuries), including four Crow Indian scouts and two Pawnee Indian scouts. Native American casualty estimates have differed widely, from as few as 36 dead (from Native American listings of the dead by name) to as many as 300.

Gen. Phil Sheridan now had the leverage to put more troops in the field. Lakota Sioux hunting grounds were invaded by powerful Army expeditionary forces, determined to pacify the Northern Plains and to confine the Lakota and Cheyenne to reservations. Most of the declared "hostiles" had surrendered within one year of the fight or infiltrated back to the reservation, and the Black Hills were taken by the U.S. without compensation.

|

The respite brought by the victory was brief for the warring Sioux. The rest of the United States regulars arrived and chased the Sioux for the next several months. By October, much of the resistance had ended. Crazy Horse had surrendered, but Sitting Bull and a small band of warriors escaped to Canada. Eventually, they returned to the United States and surrendered because of hunger. Within five years, almost all of the Sioux and Cheyenne would be confined to reservations.

In 1878, the Army awarded 24 Medals of Honor to participants in the fight on the bluffs for bravery, most for risking their lives to carry water from the river up the hill to the wounded. While some Indian accounts claimed that some soldiers had committed suicide to prevent capture (out of a belief they would be tortured, which seems to have been born out by the later discovery of some dismembered and burned body parts in the abandoned encampment along the river), most accounts noted the most accounts noted the bravery of the majority of soldiers who fought to the death.

By Don Moore

A Presidential Unit Citation for "extraordinary heroism in action against an armed enemy" was awarded to members of the Army Special Forces Studies and Observation Group assigned to Military Assistance Command in Vietnam.

This is the unit a Venice Florida dentist, Dr. Mark Bills, served with in Vietnam. He was a young captain who led an intelligence team deep behind enemy lines on 22 surveillance missions in the late 1960s and early '70s.

|

"Army regulations state the unit as a whole must display the same degree of heroism that would warrant the award to an individual of the Distinguished Service Cross," according to the information on the Internet about the award.

"Receiving this unit Citation is like getting the Distinguished Service Cross, which is right under the Medal of Honor," Bills said. "I don't feel I deserve it. But I know a lot of guys who do."

"Studies and Observation Groups performed secret missions such as training indigenous people in guerrilla warfare and sending teams, sometimes consisting of a few as eight men, deep into enemy-controlled territory," according to the information on the 'net.

"There was little or no recognition of what they did because their operations, at the time, were highly classified," according to Maj. John Plaster (Ret.) who researched declassified documents about these operations.

Eighteen Studies and Observation Groups were wiped out by the enemy. Some 25 team members are listed as "Missing in Action." No members of any of these teams returned as prisoners of war after the Vietnam conflict was over.

|

The citation was authorized by former President Bill Clinton. It covers the entire period S.O.G. operated from January 1964 to April 1972.

Lt. Gen Doug Brown, commander of the U.S. Army Special Operations Command, hosted the ceremony. Guests included Gen. Hugh Shelton, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, former S.O.G. commanders, Medal of Honor recipients and many veterans of these units.

The Venice, Fla. dentist was once a member of an elite, secret Army Special Forces group dropped behind enemy lines during the Vietnam War.

It was in his other life more than 30 years ago. He survived 22 highly classified intelligence-gathering missions while serving in the ill-fated war. Bills came home to a country that didn't appreciate his exploits or the war in which he fought.

He went on to college and dental school. For the past 22 years, he has had a dental practice in Venice.

Three decades ago, Bills was an Airborne Ranger, Green Beret and a member of the Special Forces. He was assigned to Command and Control North Military Assistance Command Vietnam's Studies and Observation Group. In short S.O.G.

"We were counter-intelligence," he said. "Six or eight of us were dropped way behind enemy lines to conduct P.O.W. snatches, check out enemy movement and do wiretaps. We tried to get a handle on what was coming south in Vietnam.

"Everything we carried was sterilized. We had no dog tags, and there were no labels on our clothing," Bills explained. "We carried nothing to indicate we were U.S. soldiers, even though it was very obvious we were.

"We knew if we were captured we would be shot as spies. The enemy hated the S.O.G. group. We had a $5,000 to $10,000 price on our heads," he said.

|

A Captain and team leader of one of these Special Forces groups, Bills and an American First Lieutenant, who served as his executive officer, would be flown by helicopter behind enemy lines with four to six Montagnard tribesmen.

Members of a six-man recon team practice an "Action Drill" in Vietnam. This was a drill so all members of the team knew what to do if they were ambushed by the enemy. The first thing they did was get out of the area with all of its members as quickly as possible.

Members of a six-man recon team practice an "Action Drill" in Vietnam. This was a drill so all members of the team knew what to do if they were ambushed by the enemy. The first thing they did was get out of the area with all of its members as quickly as possible. Photo provided

"The Montagnards, the hill people of Vietnam, were recruited by us. They hated the Vietnamese. They thought it was marvelous they got paid to kill 'em," Bills said.

When they went out, the group was scheduled to spend a week on the ground. They took everything they needed with them.

"In those days, I weighed 165 pounds and carried 135 pounds of gear. Besides my car-15 (a collapsible stock version of the M-16 rifle) I wore an old Browning Automatic Rifle belt in which I carried 36, 20-round magazines of ammunition for my rifle, two 30-round clips taped end-to-end in my car-15, a .357 magnum Smith & Wesson pistol, a little M-79, 40-millimeter grenade launcher, a bandolier of high explosives and phosphorous grenades, some C-4 explosives, smoke grenades, a knife, water, and food.

"By the time you add it all up, you've got a pretty heavy load," Bills said.

"The area of Northern Laos we operated in had some very nasty mountain terrain. There were only so many places you could put a team in or land a helicopter. After a while the enemy had us figured out.

|

"They got pretty sophisticated tracking us," he said. "When they figured out where we were trying to go, they called in their hunter-killer teams of 100 to 200 people or more that would come after us."

After the first three or four days on the ground, a thing usually got complicated for the team. Although the probes were designed to last seven days, they almost never did. If they stuck it out behind enemy lines for a week, they receive a star for valor. There weren't too many of them handed out.

"Anyone who got shot, we'd carry out with us. We didn't leave anyone behind.

"The Montagnards were Buddhists. They had to have a body or their soul wandered the earth aimlessly.

"We'd never leave our partner behind. We'd both die before we'd leave the other Ranger," Bills said with conviction.

"Special Forces are a really unique group of people. These were professional soldiers. They were all pros. Some of those guys I worked with had been in the Army longer than I was alive. It was probably one of the finest moments in my life," Bills said.

"In Vietnam, you got pretty good at this after a while," he added. "You either got good or you got dead."

When it was time to get out of Dodge in a hurry, a Huey helicopter would fly in and hover with a couple of ladders flapping loosely as members of the recon team climbed aboard.

|

When it was time to get out of Dodge in a hurry, a Huey helicopter would fly in and hover with a couple of ladders flapping loosely as members of the recon team climbed aboard.

Trouble was many of the young soldiers in the Regular Army who were sent to war in Southeast Asia lacked training.

"A lot of our guys got killed in Vietnam because of inexperience and stupidity. Often times, it wasn't their fault. It's just what happened," he said.

"The enemy didn't have better soldiers. They were just better-trained than the average American soldier," Bills said. "Not only did the enemy know the terrain, but they had been fighting much longer than our unseasoned Americans."

By the time Bills got to Vietnam, as a member of the Special Forces, he had three years of training. He had a fair idea of front line conditions.

Even so, he said, "It still dries our mouth out pretty well when you're dropped behind enemy lines. Anyone who has ever been shot at will tell you they probably got the tremors."